Raising black student enrollment at UGA still a challenge

Amalie Rosales asked a group of African-American students at a University of Georgia reception in Atlanta a question that reflecting concerns about what she will face as an incoming minority student.

“How do you view diversity on campus?,” asked Rosales, 18, a senior at Sandy Creek High School in Fayette County.

Freshman Caleb Kelly, a panel member at UGA's reception to recruit minority students, told Rosales and the audience of about 200 prospective students, parents and alumni about witnessing campus history a week earlier. Three students, each from metro Atlanta, were sworn in as student government president, vice president and treasurer — the first time all are African-American.

The new treasurer, Destin Mizelle, was pointed out standing in the back of the room. Loud cheers and applause filled the room.

For many past, present and prospective African-American UGA students, the elections represent a moment of pride, but it also reflects discomfort concerning their small numbers at one of the state’s most venerable institutions. Although more than one-third of public school students in Georgia are African-American, just one in 12 students at the state’s flagship university are black, a statistic that has changed little over decades.

UGA’s African-American student enrollment — despite programs to improve the numbers — is less than several similarly-sized public universities in Georgia, such as Georgia State (41 percent), Kennesaw State (22 percent).

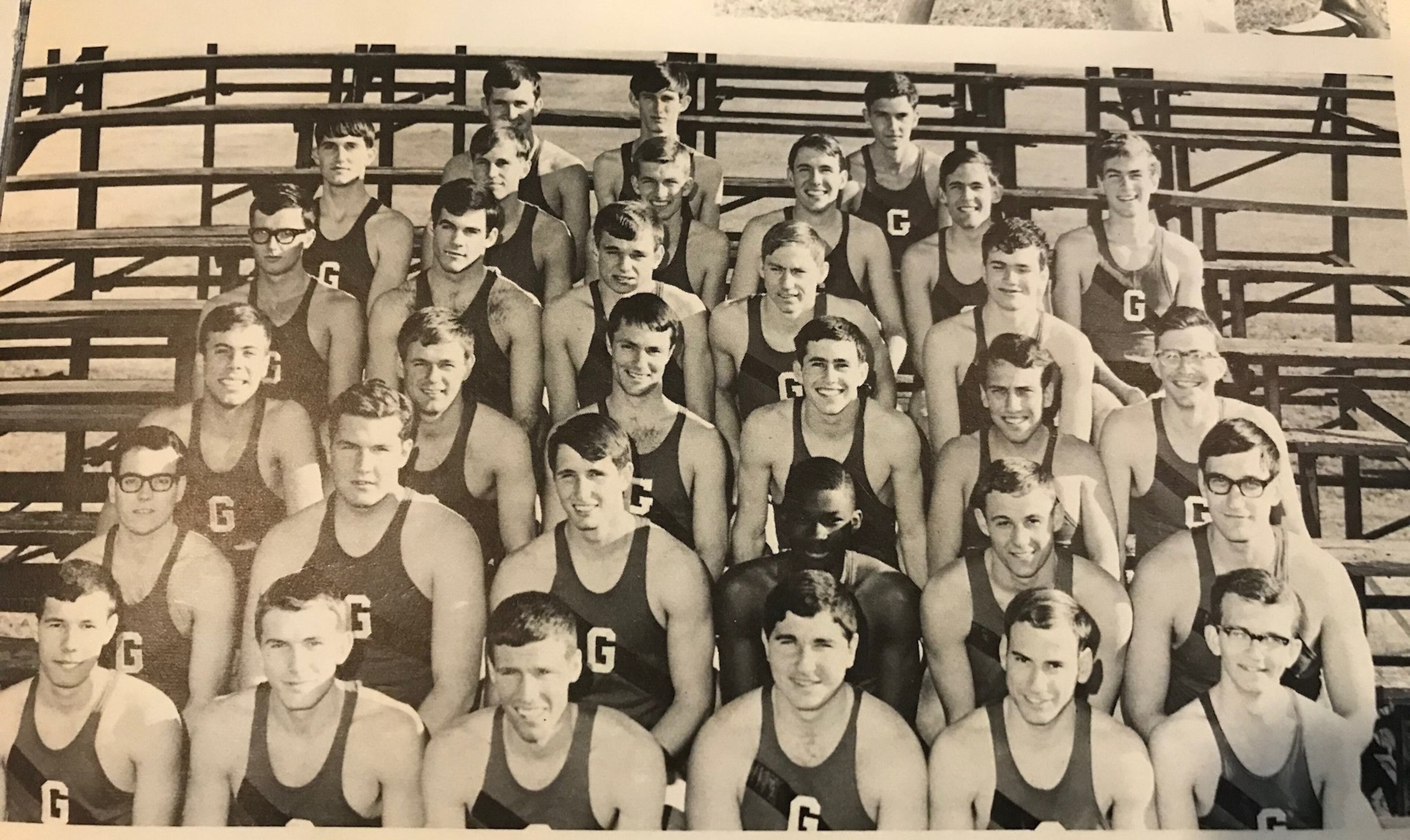

“Our schools ought to reflect what the state looks like,” said Harry Sims, 68, who enrolled at UGA in 1967 and became its first African-American varsity athlete. Sims remained in Athens, became an Athens-Clarke County commissioner and is now running for mayor.

UGA’s challenges to increasing African-American enrollment range from nearly two centuries of racist exclusion that still resonates for some black students, years of not doing enough to recruit students in its backyard and accusations of racism on and around campus, past and present students said.

Money is another factor. The university is one of the priciest options in the University System of Georgia, about $25,000 a year for a Georgia resident. Cost is often the deciding factor for many African-American students, who on average come from homes with lower household incomes.

The median U.S. African-American household income is about $40,000. The median household income of a UGA student is about $130,000, according to The New York Times. Tuition and fees for new undergraduate students from Georgia has doubled in the last decade.

And, when young students arrive on campus, they see only a small percentage of faces that look like theirs, which can discourage some from attending.

University administrators note its enrollment percentage is rising – this year’s 8.5 percentage is the highest since they started tracking it – and point to other data about African-American students to contend progress is being made.

“We may not be where we want to be, but we feel we are making significant progress,” said Michelle Garfield Cook, UGA’s chief diversity officer.

Challenges to enrollment

More than six decades after the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision declared public school segregation unconstitutional, African-Americans are under-represented not only at UGA but the South’s flagship universities. African-American student enrollment ranges from four percent at the University of Texas to nearly 13 percent at the University of Mississippi. UGA is in the middle among these schools, at 8.5 percent.

Some argue the numbers reflect an unwillingness to make campus diversity a priority. In the last 20 years, UGA’s efforts have increased the percentage of African-American students by 2.3 percentage points.

“If you truly want equity in your state and in general, you have to work with school districts to bring about change, you have to constantly ask why your institution is not diverse, and you have to consider diversity as an opportunity not a struggle,” said Marybeth Gasman, director of the Penn Center for Minority Serving Institutions.

While UGA leaders stress their desire to become more racially diverse, the university is also becoming more selective. This year’s “typical” freshman student had a 4.0 grade point average, a 1360 SAT score and had taken eight Advanced Placement courses. UGA’s undergraduate acceptance rate has declined nine percentage points since 2011, the year state lawmakers changed criteria for the HOPE Scholarship.

The average SAT scores for first-year African-American UGA students is about 100 points below the overall numbers, according to UGA data. Some education experts have studied the issue of testing and concluded that that standardized tests are culturally-biased. They recommend that colleges factor in longstanding concerns about such exams to help level the playing field.

Many African-American students in Georgia don’t have access to the high-level resources to succeed in applying to tops universities, such as test preparation classes or advanced placement classes.

They might have been set back further by 2017 legislation action when lawmakers changed state policy for subsidizing the cost of high school Advanced Placement exams, which allows students to get into high-level classes and gives a student a leg up in college admissions. The state used to ensure that every student from a low-income household got to take one AP exam regardless of the subject. Under the new policy, the subsidy is available to any student, regardless of household income, but only if they test in a science, technology and math subjects.

African-American students are also more likely to attend high schools that receive less government funding or have greater teacher turnover. The litany of deficits from which they start leads to results that can negatively affect college admission. For instance, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation also found that white students are about three times more likely to be enrolled in gifted programs.

UGA also is more aggressively competing against other universities for high-achieving African-American students.

University officials say some African-American students who turned them down did so because they received better scholarship packages from other universities.

And when students get to campus, they find a small percentage of faces that look like theirs. That can be a shock.

“I think when you first step on campus and you see there’s nobody who looks like me, that can be very discouraging and that can decide what you’re going to do, if you’re going to commit or go somewhere you know you’ll be more comfortable at,” said Charlene Marsh, the UGA student vice president.

Mizelle, who excelled at a high school that is 95 percent African-American, had similar struggles.

“To be in a classroom and just you, you’re the only African-American person and you feel you have no one to talk to or have a study group together, it’s hard to adjust to and it makes you feel kind of average … It took a minute to realize I’m far from average and doing a lot of soul-searching and pride-building,” said Mizelle, who graduated from Banneker High School in College Park.

Many African-American students say they start friendships with each other as freshman to adjust. Many are involved in the same groups and study together. Some joke all black students known each other.

Marsh said she felt more at ease when older African-American students became mentors, helping with the academic adjustment and advising her on how to build relationships with students of different backgrounds.

Several studies have found minority students often get better grades in classes taught by someone from their racial background.

Greater racial and gender diversity in student and faculty leadership is important, Marsh said.

“There’s just something beautiful in seeing people who look like you in positions of leadership,” said Marsh, 20, a third-year political science and international affairs student from Norcross.

University leaders say greater diversity improves the learning environment by sharing a variety of ideas. Many business leaders say it’s important because they need more college-educated workers of all races to keep Georgia economically competitive.

UGA’s efforts

UGA admitted 42 percent of African-American applicants last year, an 11 percentage point increase since 2013, the university said. The admissions rate in 2017 for all students, though, was 54 percent.

The university has struggled to find ways to boost enrollment of black students. A key component to one diversity effort, a point system that gave extra credit to minority applicants, was challenged in court and ruled unconstitutional in 2001. Today, the university's work ranges from recruitment events by African-American alumni, to a program that brings each public school student from Clarke County on the UGA campus every year to raising more money for scholarships for low-income students and extending their outreach to middle school students.

African-American alumni have tried to raise more scholarship funds, recognizing that the cost sometimes prevent students from enrolling and remaining. The university is in the midst of a $1.2 billion capital campaign, which includes goals of more scholarships for low-income students.

But, the most effective recruitment tool, they believe, is bringing potential students onto campus. This weekend, UGA is hosting prospective minority students, an effort that began in 2004.

“What we have told them is to come on campus. See what the campus has to offer,” said Arthur Tripp, a 2009 UGA graduate who focuses on student affairs and diversity as an assistant to the university’s president.

Yana Obiekwe, 17, a senior at Grayson High in Gwinnett County, said seeing students of color on the pre-med track she’s considering during one of those weekend trips sold her on the university.

“Wow, this is going to be me in four years,” she told herself.

Campus officials say the enrollment percentages are not the entire story when it comes to African-Americans at UGA. The university noted this month between 2012 and 2016 that 143 African-American students earned doctoral degrees from UGA, more than any flagship school in the nation, according to a National Science Foundation survey. Its African-American graduation rate is nearly 80 percent, according to one report last year, almost the same as the rate for all students.

“We see those things as part of the larger picture,” said Cook.

In some ways, UGA has become more racially diverse. Nearly one-third of its students are non-white, up eight percentage points over the past decade. The percentage of non-white faculty has nearly doubled during that time, from about 16 percent to its current 28 percent. However, about five percent of UGA’s faculty are African-American, which hasn’t changed much in the last decade.

The history

And the larger social scene in Athens can be a source of discomfort, from the history of racism to more recent events.

Founded in 1785, UGA was the first state-chartered university in the nation. Black students, though, weren’t admitted until 1961. The first two African-American students weren’t welcomed with the same enthusiasm as this year’s new student government leaders.

Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter-Gault applied in 1959 but were told that all dorms were full. They re-applied every semester thereafter and got the same response. They sued in federal court and a judge ordered UGA to admit them. A white mob rioted outside Hunter-Gault’s dorm.

Today, a campus building near the chapel is named after the two trailblazers.

More recent events include the discovery in 2015 by work crews of the remains of more than 100 souls, many African-American, during an expansion of UGA's Baldwin Hall. African-American leaders criticized the way the disinterment and plans to rebury the remains were handled. Several history professors and community leaders are also concerned about the university's ongoing research efforts of the grave sites, saying among other things, that UGA needs to conduct a thorough exploration of slavery and its connection to the university.

As that is going on, the university must compete with others where a more diverse student body is an attraction.

Decatur-native Sierra Porter, 22, said she chose Georgia State over UGA, in part, because of its location in the heart of Atlanta.

“It was a way for me to get away without having to be too far away and I enjoyed the opportunities that GSU has to offer,” said Porter, a senior majoring in journalism, referring to Atlanta’s more expansive media outlets.

She was also drawn by GSU’s student diversity. Porter said her mother attended UGA and faced some racism from students and faculty. A professor recommended she drop his class because most students of color fail it. A student once called her mother a racist epithet, Porter said.

UGA’s new student government leaders are involved in trying to make prospective students feel more comfortable on campus.

The new student government president, Ammishaddai Grand-Jean, is cognizant of the importance of their elections to improving the enrollment numbers.

“It sends out a statement that there are black students at UGA,” said Grand-Jean, 21, a third-year student from Jonesboro majoring in political science and economics.

Grand-Jean said he was the only African-American student in his high school class to choose UGA. As student government association president, he said his to-do list will include recruiting more African-American students and is confident it will happen. His team’s campaign motto was “believe.”

“I think our image alone is going to change the level of black enrollment and minorities here at UGA next year. You can write that down or mark my words,” he said with a smile.

UGA African-American enrollment:

Year percentage

1976 3.55%

1985 5.1%

1995 6.55%

2000 5.8%

2005 6.3%

2010 7.7%

2017 8.5%

Source: University of Georgia

African-American enrollment at various Georgia colleges & universities:

Institution percentage

Georgia State University 41%

Kennesaw State University 22%

Emory University 9.5%

University of Georgia 8.5%

Georgia Tech 6%

Sources: University System of Georgia, Emory University

Undergraduate African-American enrollment at southern flagship universities bordering Georgia:

Institution enrollment pct.

University of Alabama 10.6%

University of South Carolina 10.2%

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill 8.1%

University of Tennessee 6.5%

University of Florida 6.4%

Sources: Universities of Alabama, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee