The Economic Policy Institute issued a recent analysis that found teachers were paid 21.4% less in 2018 in weekly wages than similar college graduates after accounting for education, experience, and other factors.

A nonpartisan think tank, EPI describes the percent by which public school teachers are paid less than other college-educated workers as the “teacher wage and compensation penalty.” The report said the penalty reached a record high in 2018.

The analysis finds the Georgia gap is even larger than the national average; in Georgia, the pay gap between teachers and similar college graduates last year was 25.4% — which gave us the 9th largest gap in the country.

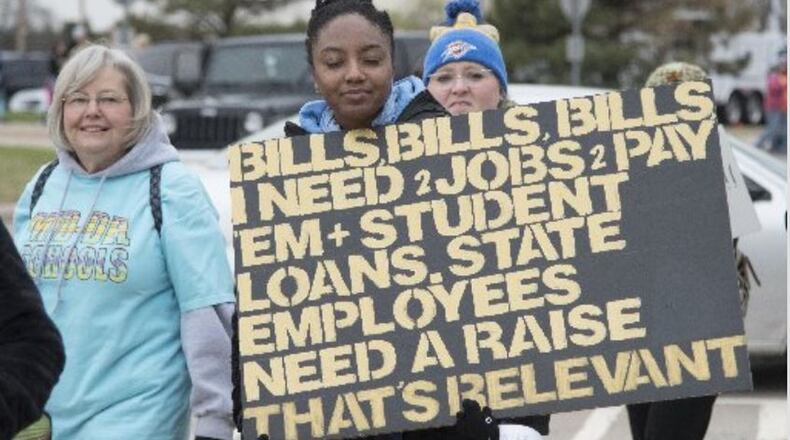

Several of the states with higher gaps have seen teacher protests, including Arizona, Virginia, Oklahoma, Colorado and North Carolina. (Teacher groups in North Carolina and South Carolina protested last week to demand higher pay.)

According to the analysis: The average weekly wages of public school teachers (adjusted for inflation) decreased $21 from 1996 to 2018, from $1,216 to $1,195. In comparison, weekly wages of all other college graduates rose by $323, from $1,454 to $1,777 over this period.

The analysis concludes the teacher weekly wage penalty has grown from 5.3% in 1993 to 12% in 2004, before reaching a record 21.4% last year. While diminished teacher pay has been blamed on the recession, the report says state priorities and policies played a major role, citing research finding that most of the 25 states that were still spending less for K–12 education in 2016 than before the recession also chose to enact tax cuts.

Among those states with the greatest reductions to their education budgets that still opted to cut taxes between 2008 and 2016 was Georgia.

The benefits teachers earn are often presented as a counterweight to the low pay, but EPI Distinguished Fellow Lawrence Mishel and EPI Research Associate and University of California economist Sylvia Allegretto said benefits, while reducing the penalty, did not negate it.

When you look at wages plus benefits, teachers earned 13.1% less than similar college graduates in 2018. (To address the nine-month contracts that teachers have, researchers examined differences between teachers and other college graduates in weekly wages for weeks worked.)

In a statement, Mishel said, “It’s no surprise that the states that have seen teachers strike and walk out over the past year are the states that have some of the highest teacher wage penalties. While teacher pay is only part of the story, it is an important element. If we are going to have excellent schools, we must make sure that teachers are paid for their work.”

The stagnant wages may explain why a national poll last year by Phi Delta Kappa International found the majority of parents don’t want their children to become teachers. And why, in a Georgia Department of Education survey of 53,000 current and former teachers released in 2016, two out of three respondents said they are unlikely or very unlikely to recommend teaching as a profession to a senior about to graduate from high school. That reluctance is troubling because of the role teachers have played in inspiring their students to pursue careers in education.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured