Amid criticism, UGA looks closer at its slave history

The University of Georgia, founded nearly eight decades before the start of the Civil War, proudly proclaims itself as “the birthplace of public higher education in America,” but that title comes with an asterisk.

Amid the backdrop of teaching and learning was also a lesser-known history entangled with slavery.

During those early years, records show enslaved workers cleaned buildings, started fires to keep students warm and performed other tasks for students and the faculty and administrators who owned them.

Now, the university wants to know more about that time period and is reviewing proposals from faculty to research that history from UGA’s founding to 1865, the year the war ended. But critics say the school’s research plan — and the $100,000 to do the work — does not go far enough.

>> RELATED | UGA accepting proposals to study role slavery played in its history

UGA President Jere Morehead declined The Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s requests for an interview. The university sent a statement saying, in part, “it is our hope that this research will culminate in one or more definitive, publishable histories on the subject.”

The criticism is part of an ongoing dispute between university administrators and some current and former students, faculty and community leaders over how UGA has managed issues concerning race, as well as its engagement with the surrounding black community that has long been underrepresented on campus.

Critics say the school mishandled the discovery of the remains of several dozen African Americans near its Baldwin Hall in late 2015 by inadequately engaging faculty and community leaders in researching and exhuming the remains. They want the university to issue some form of reparations to the descendants of those enslaved workers. They also say UGA is not doing enough to recruit black students from the Athens area.

For longtime residents who witnessed the resistance to UGA enrolling its first black students in 1961 and a federal program that displaced 40 African American families that decade to build student housing, the current concerns are another example of how they say Georgia’s flagship school doesn’t get it.

The friction in Athens comes amid milestones in the university's enrollment, promotion and support of African American students. UGA last year reported more than 8% of its students are African American, a record. Also last year, for the first time in UGA history, students elected African Americans to each of the top three positions in its undergraduate student government association. UGA has also increased its scholarships for students with financial need and is in the process of naming its College of Education after Mary Frances Early, its first African American graduate. The state's Board of Regents is scheduled to vote on the naming proposal this month, a UGA spokesman said.

>> READ | Activists want UGA to offer reparations, fund center to study slavery

But there have been troubling moments involving race on campus in the last year. A fraternity was suspended in March after a video appearing to show some of its members using a racial slur and mocking slavery went viral on social media. Also last year, a white Georgia baseball player was dismissed from the team after allegedly making racial slurs toward an African American UGA football player during a game.

Sophomore Arianna Mbunwe joined a rare march and sit-in of the university’s administration offices near the end of last semester in support of reparations demands, higher pay for workers and better communications with community leaders.

She learned about the Baldwin Hall discovery last year, and it stirred her interest in addressing racial disparities on campus. Mbunwe, like many African American students here, has mixed emotions about the university.

“I love this school and I’m proud of this school,” said Mbunwe, 19, who grew up in Temple, Georgia, and is majoring in genetics and biology. “But at the same time, I’m frustrated by their unwillingness to address these inequities.”

UGA officials said in an interview Wednesday with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that it understands the concerns. They say they worked diligently and thoughtfully on the Baldwin Hall matter and other issues and note several ongoing and recent programs to help local students.

“This whole situation has allowed us to dive deeper into the Athens community in a way that maybe we haven’t before,” said Alton Standifer, assistant to the president. “It’s an exciting time to be in the Athens community.”

Researching a painful history

By some measures, UGA is on a roll. It was ranked the nation’s 16th best public university in the coveted U.S. News & World Report annual rankings released last month. It’s receiving more research money and learned last week it will lead a federally funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine. And its beloved Bulldogs are again a serious contender for the national football championship.

For some, though, UGA’s past has clouded the cheerful news.

The Baldwin Hall burial site discovery galvanized some students, teachers and activists. They believe the activism, particularly a documentary called “Below Baldwin” by former UGA student Joe Lavine, resulted in UGA deciding to research its history concerning slavery.

Nationally, colleges became interested in exploring this history about a decade ago. Emory University held the first major conference on slavery and higher education in 2011.

Led by the University of Virginia, 56 colleges and universities are part of the Universities Studying Slavery commission. UGA is not part of the commission. The Virginia Theological Seminary announced last month it’s creating a $1.7 million reparations fund, becoming one of the first schools to set aside money specifically for the descendants of the enslaved. The funds will be used partly to help aspiring African American clergy in the Episcopal Church and support the needs of enslaved descendants.

>> READ | Black higher-ed and a brewing debate over reparations

Researching the history is difficult. In some cases, only the first names of slaves are available. Other records are spotty. Some descendants know little about the history of enslaved family members who worked at and near the schools.

University of Virginia researchers published a book in August that found horror stories such as an incident in 1856 where a student severely beat a 10-year-old enslaved girl who worked at a nearby boarding house. The student avoided expulsion by apologizing — to the slaveholder. The book came from the ongoing effort to tell “a fuller history,” university officials said on its website.

Researchers have found a myriad of ways that slavery benefited colleges. Brown University in Rhode Island said in a report “there is no question” slavery underwrote the growth of the Ivy League school. The Virginia Theological Seminary found slaves owned by a construction contractor built one of its halls, according to news accounts. Emory apologized in 2011 for its history involving slavery, which included a top official who owned an enslaved woman.

Georgia faculty members, such as associate history professor Chana Kai Lee, would prefer the research extend beyond the end of the Civil War. She’s part of a team researching that history. The team’s research has included searching for oral histories of African Americans who lived around that time.

From slaves to trailblazers

Elvir, Sam, Louisa, Hanson, Caroline, Sophia

They’re some of the names of the enslaved who worked on the campus, according to probate records posted on a website called “UGA and Slavery,” created by a group of UGA professors. Another website, the “African American Experience in Athens,” has Board of Trustees minutes documenting campus interactions involving slaves.

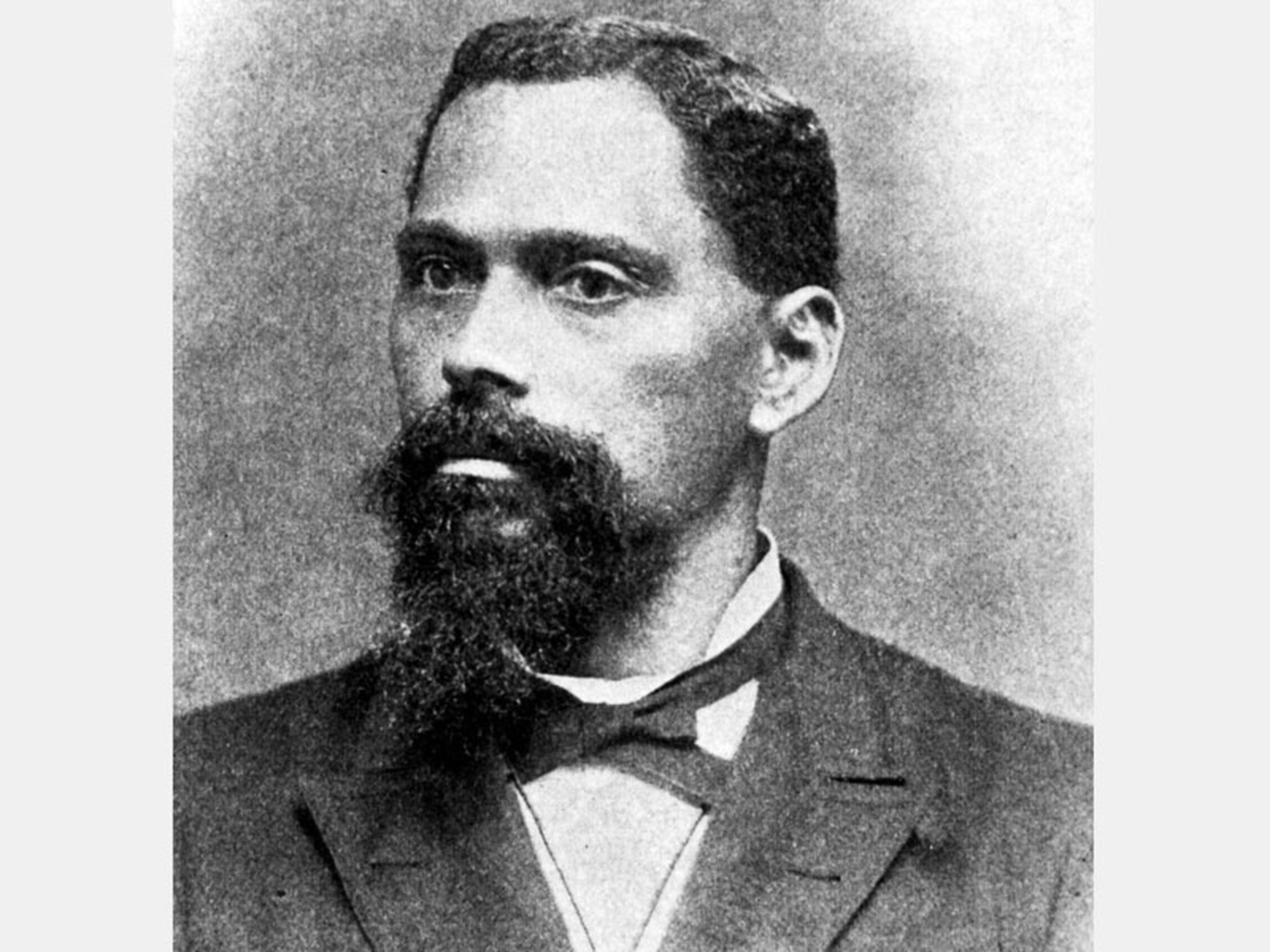

One of the few slaves with a first and last name available is Lucius Holsey. Born near Columbus in 1842, Holsey was the son of his white slaveholder, James Holsey, and an enslaved woman. Records show Richard Malcolm Johnston later became Holsey’s slaveholder. Johnston became a professor at the school in 1857, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Holsey learned to read, despite laws against slaves learning how to do so. He later founded Paine College, a historically black school in Augusta. Holsey’s descendants include David Franklin, the late ex-husband of former Atlanta Mayor Shirley Franklin, according to DeKalb County CEO Michael Thurmond, who has authored two books about African American history in Georgia. Franklin still has Holsey’s bishop cup and an original photograph, she told the AJC.

Samuel F. Harris was born 10 years after the Civil War, but UGA historians say his story shows the impact of slavery even after the war. Historians say Harris listened to lectures while working as a custodian on campus and was taught by some professors. The university refused to grant him a degree because he was black, researchers say. Morris Brown College in Atlanta awarded Harris a master’s degree.

Harris is credited with building the public education system for black children in Athens. One school, the Athens High and Industrial School, was established in 1916 and became the first four-year high school for black children in Georgia. A plaque about its history stands on a lot shaded by a handful of trees less than a mile from the famed arch that welcomes students to UGA’s Athens campus.

“They understood at the end of the day their fate was based on what they could do for those coming after them,” said Lee, the professor.

Righting the wrongs

Community leaders like Alvin Sheats say the campus seems miles away to many nearby African American students, which they believe is a remnant of its history before and in the early years after slavery. Last year, about 2.4% of UGA’s undergraduate students came from Clarke County, where UGA is located, university records show. Seven Georgia counties have more students who attend the state’s flagship university. The records are not broken down by race.

UGA officials said they have more than 50 initiatives with the county school district, a college advisement program for high school students and programs that bring each public school student from Clarke County on the Athens campus every year. One idea that came from campus-community discussions after Baldwin Hall was the Georgia Possible Program, a leadership and mentoring program with 29 students. UGA leaders say the program will grow.

“There’s not a corner of this community where there’s not some interaction” from UGA, said Alison McCullick, its director of community relations.

Still, Sheats and others want to see the university offer more scholarships to local students and provide early education in the area.

“It would give so much hope to a challenged population,” said Sheats, president of the NAACP’s Athens-Clarke County branch.

The city’s poverty rate is 34%, more than twice the statewide average, U.S. census data shows. Longtime Athens resident Linda Lloyd frequently mentions the poverty rate in her discussions about the university, saying it needs to increase hourly wages. UGA is the largest employer in Athens-Clarke County, according to its economic development department.

“Give these descendants an opportunity to improve their lives,” said Lloyd, director of the Economic Justice Coalition, a community service organization, who holds a master’s degree from UGA.

Some call it a form of reparations. Nationally, polls show the idea of reparations for the descendants of the enslaved is not popular. There's healthy debate on campus about it, students say. Several Democratic Party presidential candidates and members of Congress have spoken in favor of reparations in recent months.

“I think, really, it’s a frivolous, wasteful occupation,” said Robert L. Woodson Sr., an African American who is the founder of the Woodson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based organization that describes its mission as helping communities empower themselves.

Woodson wrote an op-ed earlier this year in response to the call for reparations. Determining who would get reparations would be difficult, he said. Woodson added it “provides a convenient excuse for failure.”

Back at UGA, Lee and her colleagues sent their proposal to submit to administrators. Activists are talking about voicing their concerns with the state’s Board of Regents, which oversees operations at the university and 25 other state schools.

Mbunwe said her mother was initially concerned about her getting involved. Mbunwe said her class schedule is full this semester, but she’s looking for other ways to help, such as showing the documentary to raise awareness among other students.

It’s her way, she said, of supporting the cause.

BY THE NUMBERS

$100,000 — funds the University of Georgia has committed for faculty to research its history of slavery

56 — the number of member schools in Universities Studying Slavery

$1.7 million — money the Virginia Theological Seminary has committed toward slavery reparations

8% — the University of Georgia’s African American student enrollment

Sources: The University of Georgia, the University of Virginia, the Virginia Theological Seminary