Georgia families brace after Kemp extends closure of schools

When Gov. Brian Kemp ordered the continued closure of public schools into late April, it extended the educational turmoil for 1.8 million children and their parents, and for teachers such as Sarah Ott, who has kids of her own.

She teaches middle school science and, from a public safety standpoint, thinks Kemp made the right decision to put the brakes on the accelerating number of coronavirus infections in Georgia.

But still, the chaos.

Ott has had to figure out how to move her curriculum online while learning how to talk to her students through a computer screen. Her daughters, ages 4 and 6, are home since their schools are closed, too, and, just like most every other parent in Georgia, or on the planet probably, she has to keep them occupied while doing her job.

Home confinement does things to people: teacher Sarah Ott channels Ariel the mermaid, with a little help in the background

During normal times, she and her husband are so busy with work that they often rely on restaurants for their meals, yet the restaurants are closed.

On top of all that, their housekeeper, fearing infection, has quit.

“I’m about to lose it,” the eighth grade physical science teacher in Dalton said. “Everything’s so crazy right now.”

Kemp, who previously ordered all schools to close through the end of this month starting March 18, is now forbidding them to reopen before April 27. Public colleges, which have already moved to online learning, will remain closed until the end of the school year. Many suspect K-12 schools will ultimately be closed for the rest of the year, too.

>> RELATED | Kemp: Georgia public schools to remain closed through April 24

“I don’t really think they’re going back,” said Tywanna Bailey-Britt, who has three children in DeKalb County schools. She laments the disruption. Prom has been canceled, and her daughter’s graduation ceremony is up in the air.

Kemp said he’d reached his decision after a “frank conversation” about the fallout for schools. “They want direction from a statewide perspective and we’re now in that place,” he told WGAU, an Athens-based radio station.

Superintendents applauded his decision.

Schools would be “negatively impacted” by returning too soon, said Chris Ragsdale, the superintendent in Cobb County. “Student and staff safety must always be the top priority.”

J. Alvin Wilbanks, who leads the Gwinnett County schools, said the governor made “a tough decision in a timely manner.” Gwinnett has had dry runs with online learning, so he was confident his system could teach students well online “for as long as is necessary.”

>>How is your school handling this extended closure? Are classes online or on paper? Are teachers using video conferences? Let us know at CoronavirusEducation@ajc.com

Atlanta Public Schools, which closed several days ahead of Kemp's mandate, will miss five weeks of in-place schooling after subtracting the upcoming time off for spring break. Superintendent Meria Carstarphen held a virtual town hall Thursday with about 1,700 watching. "It's too early to say whether or not schools are going to be closed through the end of May," she said, adding that the uncertainty "causes all kinds of angst."

She advised parents who are now effectively home-schooling that they should cap schoolwork at three hours a day for children in fifth grade and younger, four hours for kids in middle school and five hours for teens in high school.

Besides concerns about missed proms and graduation ceremonies, there is the fundamental question of missed learning. Schools that can do it have shifted to online, but it hasn’t been a seamless transition for all.

“Our biggest worry is for those kids who don’t have internet access,” said Bronwyn Ragan-Martin, the superintendent in Early County, in the southwest corner of the state. As many as half of the students aren’t showing up for some online classes, she said. As president of the Georgia School Superintendents Association, she’s heard similar concerns across the state.

She said some superintendents have been pressuring Kemp to pull the plug on the rest of the school year. The uncertainty makes it hard to plan, and some, especially older, staffers want to stay as far away from the virus as possible.

>> Follow all the AJC’s coronavirus coverage

Children and young adults rarely experience significant symptoms from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. It is far more dangerous for older people and those with underlying medical conditions. Public health experts worry about the virus spreading in the close confines of schools.

The situation has forced Ragan-Martin into a lose-lose situation: stop feeding students or risk the lives of her staff.

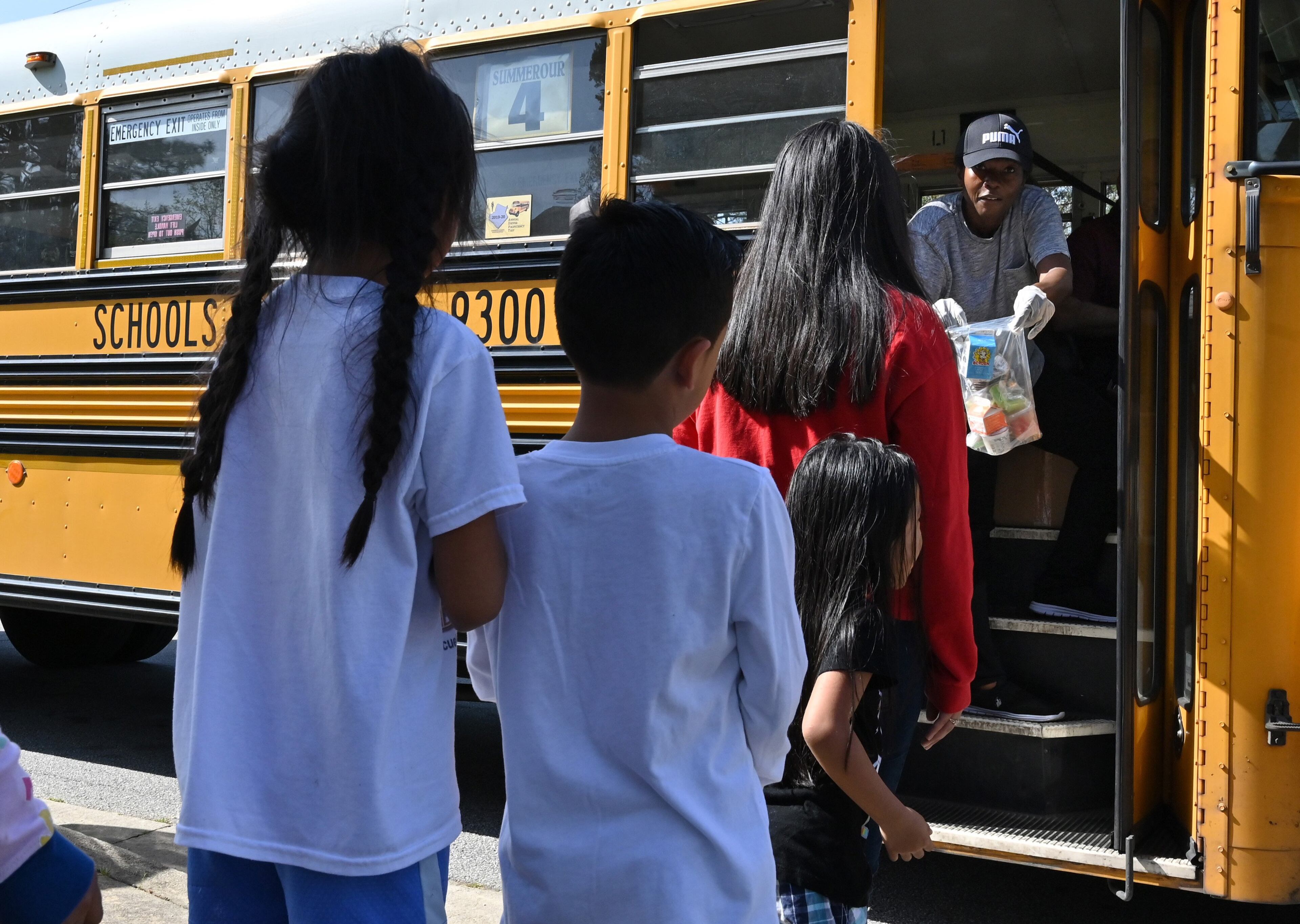

Schools have been delivering food to students who qualify for the federally subsidized school meals program, but Early County will be ending its deliveries soon. With seven confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Early County as of Thursday evening, Ragan-Martin’s food service staffers fear the deliveries are putting them at risk of infection.

“Our folks are too afraid,” she said. “People are scared.”

Ott, the science teacher in Dalton, is among those who want Kemp to throw in the towel on the school year. The virus is too dangerous, and must be stopped with months of continued social distancing, she said.

She can muddle through with online schooling. After the bumpy transition of the first couple of days, things are going well enough. She has been using a popular teleconferencing platform called Zoom to meet with her students. With students curious about the pandemic, she saw a teachable moment and has been reading the book “Hot Zone,” about the deadly Ebola virus, in a YouTube video that her students have been enthusiastic about watching.

Still, she has to keep a box of tissues near her computer because she cries every time she sees them through a screen. She misses them, and they miss school.

“There was only one kid who was like ‘woohoo, no school,’” she said. “Everybody else is sad.”

Staff writers Marlon Walker, Vanessa McCray and Kristal Dixon contributed to this article