Emory’s Slave Voyages website could help build case for reparations

Madison Marsh was researching a project for her history class at the Atlanta Girls’ School last fall when she stumbled on the Slave Voyages website.

The 17-year-old was trying to trace her ancestry to its origin in Africa. Though she knew she faced long odds against pinpointing a particular country, given the brutal execution of the slave trade, a DNA test had revealed her genetic ties to the sub-Saharan, northwestern region of the continent.

She thought that the Slave Voyages website, built and run by Emory University, might help her uncover more about America’s slave trade.

“I knew my family was from Tennessee, Georgia and South Carolina, so I started looking on the website and they had records of slave ships, years they sailed, ship names, so I said, ‘Oh, let me use this,’” Marsh said.

But, as interesting as Marsh found the online records to be, the website wasn’t as interactive as she’d hoped. That has now changed. Late this spring, after nearly eight years as a website mainly geared toward scholars of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Emory has redesigned and relaunched the site, hoping to draw in more users such as Marsh.

The scholarly database has been touted as the most comprehensive online project in the world documenting four centuries of enslavement of Africans and their transport to the Americas. Academics around the globe have contributed decades of research to the website.

While it does not reflect every journey, ship or person transported as cargo, the volume of information on the website is arresting because it documents multiple aspects of nearly 400 years of the African slave trade.

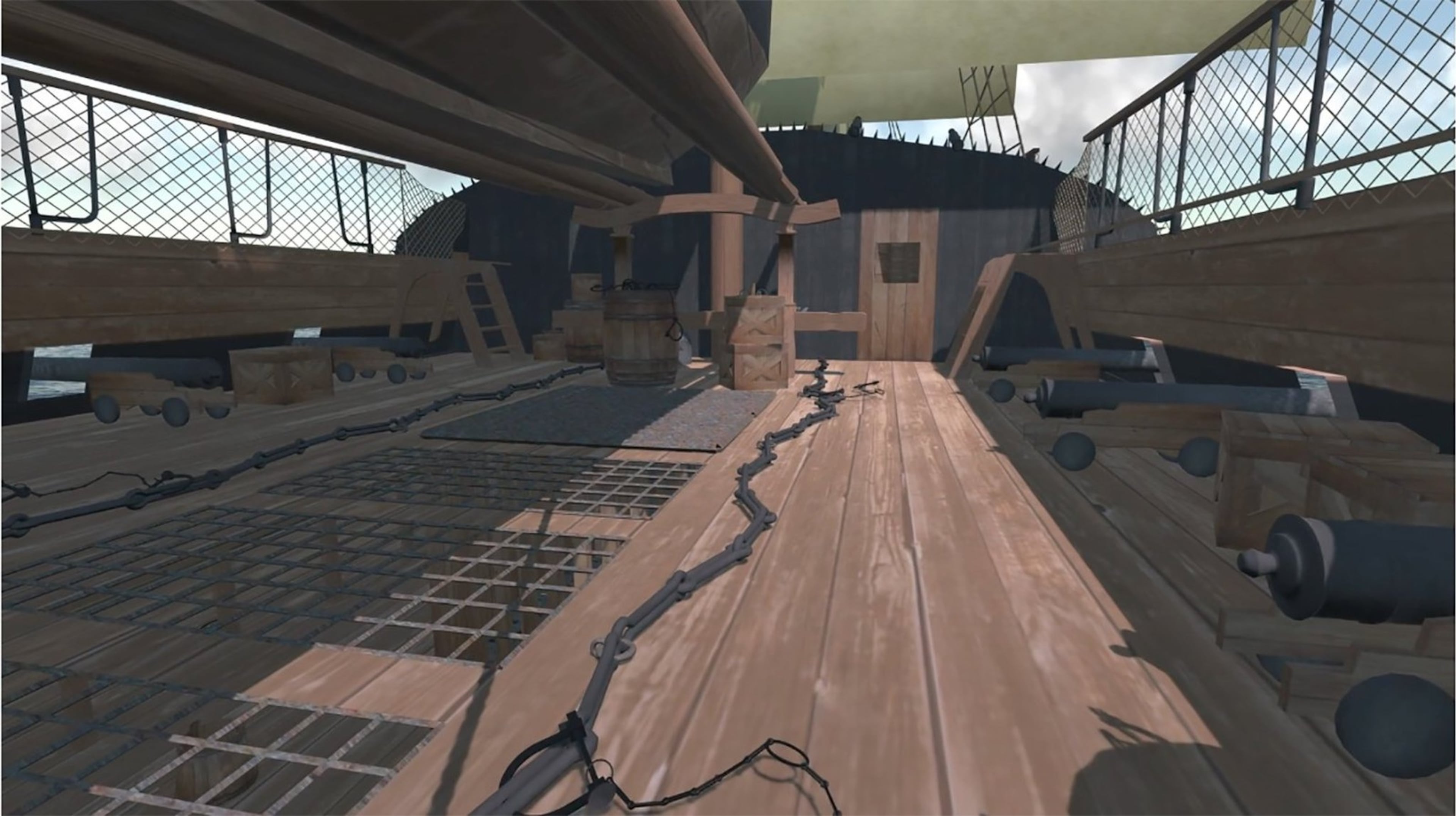

There is a 3-D animation of the slave ship L’Aurore, created using the surviving blueprints of the actual 1780s vessel. Viewers descend into the bowels of the ship to see the cramped, inhumane conditions that men, women and children were held in for months at a time. Interactive tables and charts list all the documented ships and each voyage they made, along with the names of the ship owners and captains. A country-by-country, state-by-state, year-by-year list records the number of enslaved Africans each country or colony received over the span of the trade. For each ship, there is a record of captives who survived the long journey from Africa to the Americas. There are also catalogs of the dead.

Some involved with the project say it could help reshape the latest conversation about reparations for descendants of enslaved Africans Americans.

“Before this, scholars didn’t have an accurate database of the slave trade,” said Brett Bobley, director of the office of Digital Humanities for the National Endowment for the Humanities, which, along with the Mellon Foundation, has awarded grant money to Emory for the website. “This is now the comprehensive resource.”

The data project has already been the source for major exhibitions on the slave trade and its lasting impact on the development of the Americas.

While observers say the data has limited potential for African Americans trying to trace their ancestral roots, because those loaded onto slave ships were treated as cargo rather than people, with no names recorded, only gender and approximate age, it does provide context for the forced migration that reshaped half the globe.

“I’ll never know”

For her junior-year project, Marsh, who is now a senior, used information from the database to build a map on poster-board with pushpins and strings to represent the ports where Africans were loaded onto ships, their journey across the Atlantic, and their port of landing in the United States.

After Emory relaunched Slave Voyages this spring, Marsh revisited the site and saw a new feature she wished had been there before: a special time-lapse map showing North and South America, Europe and Africa.

Beginning with the year 1500, dots of varying sizes and colors appear one by one along the shores of Africa and migrate across the Atlantic Ocean. At first, they are intermittent. As the years pass, they become a swarm. The dots dock along the shores of the Americas, mostly along the coasts of Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia and the Caribbean Islands. As the time counter moves into the 1700s, schools of dots settle along the Eastern seaboard of the United States.

The dots are a dispassionate representation of the slave ships that sailed nearly 37,000 voyages to the Americas. But pause the time counter and pop-up details appear for each ship, including country of origin, length of journey and number of men, women and children on board.

The majority of the millions of African enslaved were sent directly to the Caribbean and South America. Only about 3% of those enslaved, roughly 389,000, were brought to mainland North America.

The pernicious design of the slave trade guarantees the majority of African Americans will never figure out which dot represents their family’s beginnings in the U.S.

“With the time lapse, what you see in six minutes is 12 million people hauled off from Africa and enslaved in the Americas,” said David Eltis, professor emeritus at Emory and head of the Slave Voyages project. “One quarter of the people arriving were actually kids.”

Marsh was wistful after seeing the time-lapse.

“My people could’ve come in on this ship or that ship, but I’ll never know.”

“Critical to the work”

Eltis was a researcher in the 1970s when he started talking with others about building a repository for much of the scholarship about the slave trade. Over the years, the project grew from an analog database culled from a collection of centuries-old maps, shipping logs, ledgers of slave trading companies, wills and other documents, into a digital presentation of how the trade transformed both populations and economies.

As curators at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., were deciding how to depict the expansiveness of the slave trade, they turned to an early version of Slave Voyages.

“We went on the site and isolated some slave ships, and we got the names of those slave ships, country of origin, departure date, the number of who embarked, the number of people who disembarked and papered them over an entire wall in the exhibit on the Transatlantic slave trade,” said Mary Elliott, curator of American slavery exhibition at the NMAAHC. “How can you view it and not cry?”

The website has become a crucial resource for the museum. “There’s a lot of information still out there. But this, it blows away the notion that there’s no information about the trade, when it begins, how long it lasted and the specifics about the countries involved in the trade,” Elliott said.

Slave Voyages also will play a role in the development of the International African American Museum (IAAM), scheduled to open in Charleston in late 2021. Joy Bivins, chief curator for the museum, said the IAAM wants to incorporate the registry of slave ship names as well as a directory of African names also on the Emory site.

“This fact-finding and piecing together is really critical to the work we do here at the IAAM,” Bivins said. “When I was a student, trying to find this kind of information wasn’t easy. So, this kind of aggregation of resources and information is really important to scholars and laypeople.”

Academics have been the primary users of the site, which gets about 1,000 visitors a day. But, since the redesign, it has also drawn a stream of writers, journalists, amateur genealogists and K-12 students and teachers, said Kayla Shipp, who analyzes traffic data and fields user questions and requests through the university’s Center for Digital Scholarship.

“This was an industry”

Given the current conversation about reparations for descendants of the enslaved, the database could provide researchers with building blocks for a case in favor of restitution, said Eltis and others who developed the site.

Some House Democratic leaders are pushing for the creation of a commission that would study and develop reparations proposals.

One of the arguments against reparations by opponents is that it’s nearly impossible to determine how many Africans were brought to the country. While exact numbers may be elusive, because some records might not have survived the ravages of time, the database does account for most Africans brought here directly from their home continent. And it accounts for those brought here after initial enslavement in South America and the Caribbean. For example, between 1751 and 1858, 20,257 Africans were put on ships that landed in Georgia, mainly Savannah and Tybee Island.

Drawing on timeline data, it’s possible to track the number of people brought to America based on the cultivation and surge of certain crops, mainly rice, tobacco and cotton.

“These weren’t accidental things,” said Nafees Khan, an African American history professor at Clemson University and member of the Slave Voyages leadership team. “This was an industry. This was a trade, and people made their livings off of this trade.”

Because the website was built largely from the records of those who operated the slave trade, it’s possible to document the profit individuals made from it. Those records will be the basis of the next phase of the website — PAST, or People of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the federal government paid a number of former slave owners compensation because they lost their coerced workforce.

“Let’s get out the information out there,” Khan said. “It’s a tool that is a collection of evidence that people will make use of and forward the reparations argument.”

Khan’s view of the data’s potential impact is optimistic. Eltis said the website does help lay the foundation of an argument in favor of reparations, but it only goes so far.

“It tells you the number of people brought in and the regions from which they were taken, but it doesn’t tell you how much labor was extracted from them once they arrived,” Eltis said. “It doesn’t carry the story forward or tell you about their children, but it does paint a broad picture.”

Since the enslaved lost their birth names when they were taken from Africa and were by law forbidden to learn to read or write for a good deal of the active slave trade, individual narratives of life in captivity are rare. But the legacy of the labor they performed, and the economies they built in the Americas over 400 years, speaks volumes, Eltis said.

“It wouldn’t have been possible without a lot of (African) people,” Eltis said.

WHY IT MATTERS

The trans-Atlantic slave trade spanned four centuries, and Africans transported to North, Central and South America and the Caribbean transformed the populations and economies of those continents and regions. Emory University’s Slave Voyages website explains many aspects of the slave trade, including the movement of hundreds of slave ships across the Atlantic. It is meant to provide viewers with a deeper understand of the impact of the slave trade, but it could also help reshape the latest conversation about reparations for descendants of enslaved Africans Americans.