Another back-to-school COVID-19 challenge: Reeling in kids’ bedtimes

Alicia Simpson’s daughter may be precocious, having skipped a grade, but mom is worried that her 8-year-old is advancing too quickly in an unhealthy way.

Bradley, a rising fourth grader, used to be an early-to-bed kid but has been going to bed later since COVID-19 upended her life. She is now getting nine or 10 hours of sleep when she used to get nearly a dozen.

“For someone who clearly has a natural high need for sleep, what does this mean?” asked Simpson, who observed that her own bedtime has pushed later, too.

Simpson is experiencing something that doctors, researchers and teachers say is a real trend, with potentially harmful consequences if parents fail to rein it in. In extreme cases, they are seeing kids going to bed nearly when they used to wake up.

“It’s happening,” said Dr. Stephanie Walsh, medical director of Child Wellness at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. She is concerned because sleep affects emotional, physical and mental health — basically all aspects of life. It’s even happening in her own household: She goes to bed before her sons, but keeps them in line by reminding them she will wake them on schedule, though she admits letting them stay up later than normal, until 1 a.m.

Jordan Kohanim, a high school English teacher in Fulton County, said in the spring that her juniors were often groggy for her 10 a.m. video conferences. Many told her they’d gone to bed at 4 a.m.

“I would say 70% of my kids said their sleep patterns went off the wall,” said Kohanim, who had 108 on her roster at Milton High School. “A lot of kids are staying up very, very late.”

Body clocks take over

It’s not just high school students.

Bridget Edison teaches seventh grade English and social studies in Early County in southwest Georgia.

After schools closed in March, many of her 50 students started emailing her questions about their assignments later and later, some telling her they now slept until 2 p.m.

“In the beginning, I was pretty much on call around the clock,” she said. “I had to tell them, guys, I’m probably not going to respond to you at midnight.”

She worries about their brains adapting to the new pattern. “Getting back on schedule is going to be a nightmare,” she said.

This was predictable, sleep expert Donn Posner said.

“What happened with coronavirus is every day became a weekend,” he said, “and everybody was allowed to sleep in their own preferred phase.”

For reasons as yet unclear to science, the natural bedtime for teens generally shifts later, and the pandemic has exacerbated that tendency by removing the guardrails on their lives.

That can be a good thing, since people sleep better when the timing suits their natural rhythms, said Posner, an adjunct Stanford University clinical associate professor.

He is not a fan of the relatively early start times in U.S. high schools, which he said are “torturing” teenagers; sleepy kids perform worse academically and are like drunken drivers behind the wheel.

However, he worries about the consequences of extreme unstructured behavior during the pandemic — of going to bed, and rising, too late or at inconsistent times for months on end. Some can suffer from chronic insomnia if they ignore their body clocks for too long, said Posner, president of Sleepwell Consultants in Massachusetts and a founding member of the Society of Behavioral Sleep Medicine.

“Your brain’s going to eventually forget when to put you to sleep,” he said.

Poor sleep is associated with health risks, such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, obesity, dementia, depression and substance abuse. It can also undermine the body’s immune system, of particular concern during a pandemic.

Getting more shut-eye

Kids are not the only ones shifting later.

Jessica Harvin, another teacher in Early County, normally wakes around 4:30 a.m., but after the pandemic started, she pushed that to 8 a.m. and later.

“I’ve kind of enjoyed the sleeping-in aspect,” she said.

She appears to be part of a global trend among adults, and it’s not all bad.

Adults seem to be sleeping both longer and with more regular bedtimes, new research shows. The studies didn’t look at kids, but if they’re following a similar pattern, then that’s a good thing, experts said.

One study, based on surveys of 435 adults in Switzerland, Germany and Austria, found that after their countries locked down, they started going to bed later on weekdays but not as late as they used to on weekends. It's common to shift later on weekends, and reducing the differential is healthy. The respondents also reported getting about a quarter of an hour more shut-eye. The paper from the University of Basel, publishing in the science journal Current Biology, concluded that the respondents, most of them higher wage earners, had more flexible schedules while working from home and were therefore freer to follow their natural sleep rhythms.

Another paper appearing in the same publication found something similar happening among young adults in the United States. The study of 139 University of Colorado Boulder students found that their bedtimes shifted later by nearly an hour on weekdays but only half an hour on weekends, so their bedtimes converged. The study, by researchers at CU Boulder and the University of Washington, also found that the students were sleeping an extra half-hour on weekdays and nearly as much on weekends.

Lead author Kenneth Wright has read the European study. He said last month that he was unaware of any emerging research showing children following a similar pattern, “but both of our studies show that adults, whether they’re older or younger, are timing their sleep later, so it’s likely.”

While the extra sleep and more consistent bedtimes are healthy developments, he said, many teens may be going to bed well after they should.

The professor of integrative physiology and director of the Sleep and Chronobiology Laboratory at CU Boulder said it takes years for medical issues to develop from later and inconsistent bedtimes, so the risk of that happening during the pandemic is low. But he said a short-term trend could trigger substance abuse and other behavioral problems in some, so parents should rein it in. He recommends exposing kids to bright light in the morning, a little earlier each day.

Health isn’t the only reason to get back on track, he noted. Normal schedules will eventually return, forcing everyone to readapt anyway, “unless they’re pursuing a career as a disc jockey.”

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, during an interview with Seth Meyers on his "Late Night" show last month, said one of her younger sons is doing just that. He set up his equipment in a corner of her office, she said.

“And now he even stays up all night like a deejay,” she said. “When I get up at 6 in the morning to take a shower, he’s taking a shower to go to bed. So we’re going to have to undo some quarantine behaviors.”

The role of video games

Wright said video games are a major cause of the late-night shift.

Until a century ago when the lightbulb was invented, humans fell asleep within several hours after the sun set and woke as it rose. Now tiny lightbulbs in screens blast eyeballs with high-frequency light that inhibits the body's production of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep-wake cycles. Research shows that light has a bigger impact on kids, apparently because their pupils are larger and their lenses more transparent.

Video games also saturate brains with adrenaline, exciting them before bed when they need to be calmed.

Later bedtimes are associated with more social and health problems, he said. “In the long run, this late behavior is not a good thing.”

Kohanim, the Fulton high school teacher, said her students were up late using social media, watching Netflix together and playing a Nintendo game called Animal Crossing.

“They stay up for hours upon hours playing this weird game,” she said.

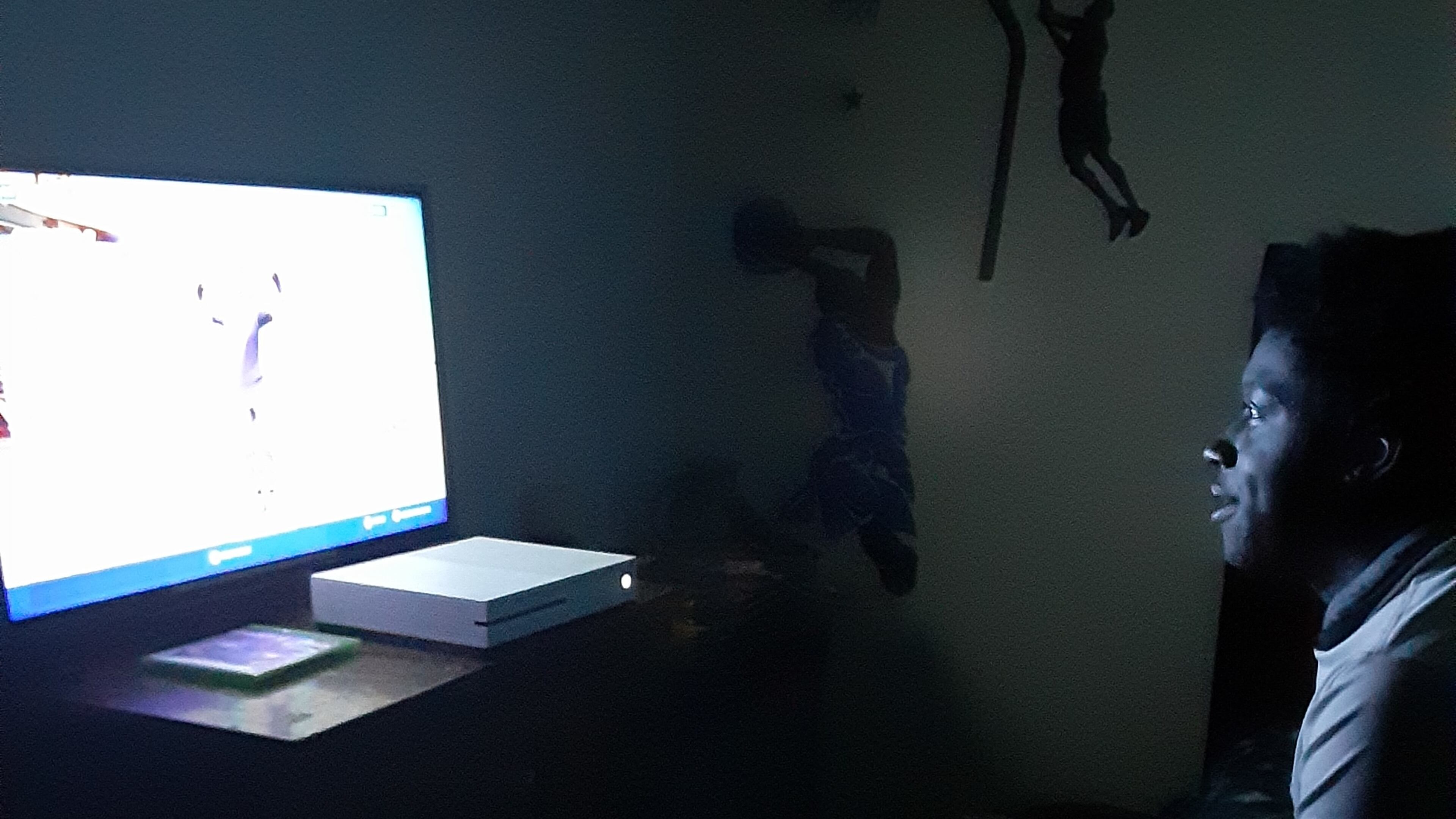

Marion Ross, 15, is among the many teens in the thrall of video games.

“I’m playing my game with other folks,” he explained one recent morning, groggy because his grandmother had awoken him at 11 a.m. for the interview.

The Macon youth plays Fortnite, Grand Theft Auto and NBA 2K remotely with his friends until after sunrise sometimes.

He lives with his grandmother, Cheryl Thomas, who has been indulging him during the coronavirus lockdown. She knows he’s bored and she feels sorry for him. Normally, she’d have him in bed by 9 p.m., because he must wake in time for the 8:30 a.m. school bus. Now, he sleeps past noon, sometimes until 2 p.m.

When school starts, she said, “That game is going to be taken away. … Sometimes you’ve got to know when to be hard on them.”

Even preteens are up late these days.

Taylor Ann Freeney, 12, used to be in bed by 9:30 p.m. Now, she is often up well past midnight.

Her mom, Tara, said she let her stay up because that’s when her friends were online, but she is starting to regret the decision.

“I haven’t been able to reel it back in,” the College Park mom said.

Taylor Ann said she’s been trying to get to bed earlier, but now she’s used to the late-night routine. At first, it was fun because in normal times she’d get picked up from aftercare at 6 p.m. and bedtime would come too soon after dinner. “There wasn’t time to do what I wanted,” she said.

The girls play a game called Roblox on their phones, often until 1 a.m. and sometimes even 4 a.m.

And why don’t they just play Roblox during the day instead?

It was hard to argue with her reason:

“I wake up too late.”

Advice to keep kids sleeping through the COVID-19 pandemic:

- Turn off all screens an hour before bed, and keep them out of the bedroom.

- Turn off overhead lights and use lamps closer to bedtime.

- Try activities that promote relaxation before bedtime, such as reading a book, playing board games, drawing, writing or listening to music.

- Create and stick to bedtime routines (especially with younger kids), such as bathing, brushing teeth, reading, singing songs or discussing the day.

- Ask younger children what questions they have about COVID-19 to get a sense of what they know or worry about.

- Ask teenagers how they are feeling, and be open to hearing their concerns.

- Avoid dismissing your kid's feelings and let them know their feelings are normal.

- Answer any questions your kids have and correct any misinformation your hear. (It's OK if you don't have the answers and need to get back to them.)

- Sleep needs decrease as people age — counting naps, toddlers need as many as 14 hours a day and preschoolers up to 13 hours; kids in elementary school need nine to a dozen hours while teenagers need eight to 10.

SOURCE: Children's Healthcare of Atlanta Strong4Life parenting guides on sleep, behavior and other issues at www.strong4life.com