Lewis found himself a confessor to those repenting of racism

It wasn’t uncommon for Congressman John Lewis’ staff to find apologies in his mail.

They came from the children and grandchildren of people who fought in the 1960s against him and other civil rights activists — and even from those who remained on the sidelines.

The Atlanta Democrat would get them in person, too, from elected officials, community leaders and others as he crisscrossed the South commemorating milestones in the hard-fought battle for racial equality.

One of the most memorable came late in his career.

In January 2009, former Ku Klux Klan member Elwin Wilson confessed to being part of the white mob that bloodied Lewis and another Freedom Rider in Rock Hill, South Carolina, nearly 48 years earlier.

Lewis noted in his 2012 book “Across that Bridge” that Wilson was the first of his attackers to apologize for his actions. Wilson traveled to Washington a short while later to meet Lewis face-to-face and ask for forgiveness.

“Without a moment of hesitation, I looked back at him and said, ‘I accept your apology,’” Lewis wrote. “This was a great testament to the power of love to overcome hatred.”

Informed by his Christian upbringing, shaped by the teachings of philosophers like Mohandas Gandhi and Henry David Thoreau and honed by mentors such as Martin Luther King Jr., Lewis’ life was permeated by love, nonviolence and reconciliation. Even in his later years, Lewis said he felt no bitterness toward the people who hurt, arrested and jailed him during his time at the forefront of the civil rights movement.

His unwavering adherence to nonviolence sometimes drew criticism from his peers, who argued his methods were insufficient for erasing the country’s deep-seeded inequalities. But as Lewis saw it, all of humanity lived together in the same house. If one section began to rot, the entire structure could be put at risk.

“The alternative to reaching out is to allow the gaps between us to grow, and this is something we simply cannot afford to do,” Lewis wrote in his 1998 memoir “Walking with the Wind.”

Pricking Consciences

Lewis’s philosophy came into focus in 1958, when the 18-year-old began attending weekly nonviolence seminars in the basement of a Nashville Methodist church.

The instructor was James Lawson, a minister affiliated with King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. While serving as a missionary in India, Lawson had studied satyagraha, the form of nonviolent resistance deployed by Gandhi to free India from English colonialism.

Lewis soaked up Lawson’s teachings like a sponge. Among them: that violence begets violence. And even the most despicable people are capable of unlearning hate when shown compassion.

“When you can truly understand and feel, even as a person is cursing you to your face, even as he is spitting on you, or pushing a lit cigarette into your neck, or beating you with a truncheon – if you can understand and feel … that your attacker is as much a victim as you are, that he is a victim of the forces that have shaped and fed his anger and fury, then you are well on your way to the nonviolent life,” Lewis wrote in “Walking with the Wind.”

Lewis and other budding activists, including Diane Nash, James Bevel and Marion Barry, began applying what they learned in Lawson’s seminars to the glaring inequities they encountered in segregated Nashville. In 1959, the group began organizing lunch counter sit-ins in local department stores.

Their strategy was firm. Show up at lunchtime, so as many people as possible would witness their struggle. Always be friendly and courteous. When faced with aggression, respond calmly and don’t retaliate.

Lewis soon moved from lunch counters to “pricking consciences” as a Freedom Rider, when he logged hundreds of miles testing desegregation orders in bus stations across the South in 1961. As mobs descended on him in Rock Hill, and later in places like Montgomery and Selma, Ala., Lewis would look his assailants in the eye.

“In order to beat people who radiate love and acceptance, an individual has to override his or her own conscience and allow anger and brutality to have its way without limitation,” Lewis wrote. “Most people cannot do this. They have a conscience.”

A ‘common bond’

With time, that strategy proved successful.

Images of marchers being ruthlessly beaten at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on March 7, 1965, led President Lyndon B. Johnson to push for the Voting Rights Act.

It helped moved people like Wilson, who said he was glad that Lewis didn’t press charges in 1961. That would have upended Wilson’s life and taken him that much longer to seek forgiveness, Lewis suggested in “Across that Bridge.”

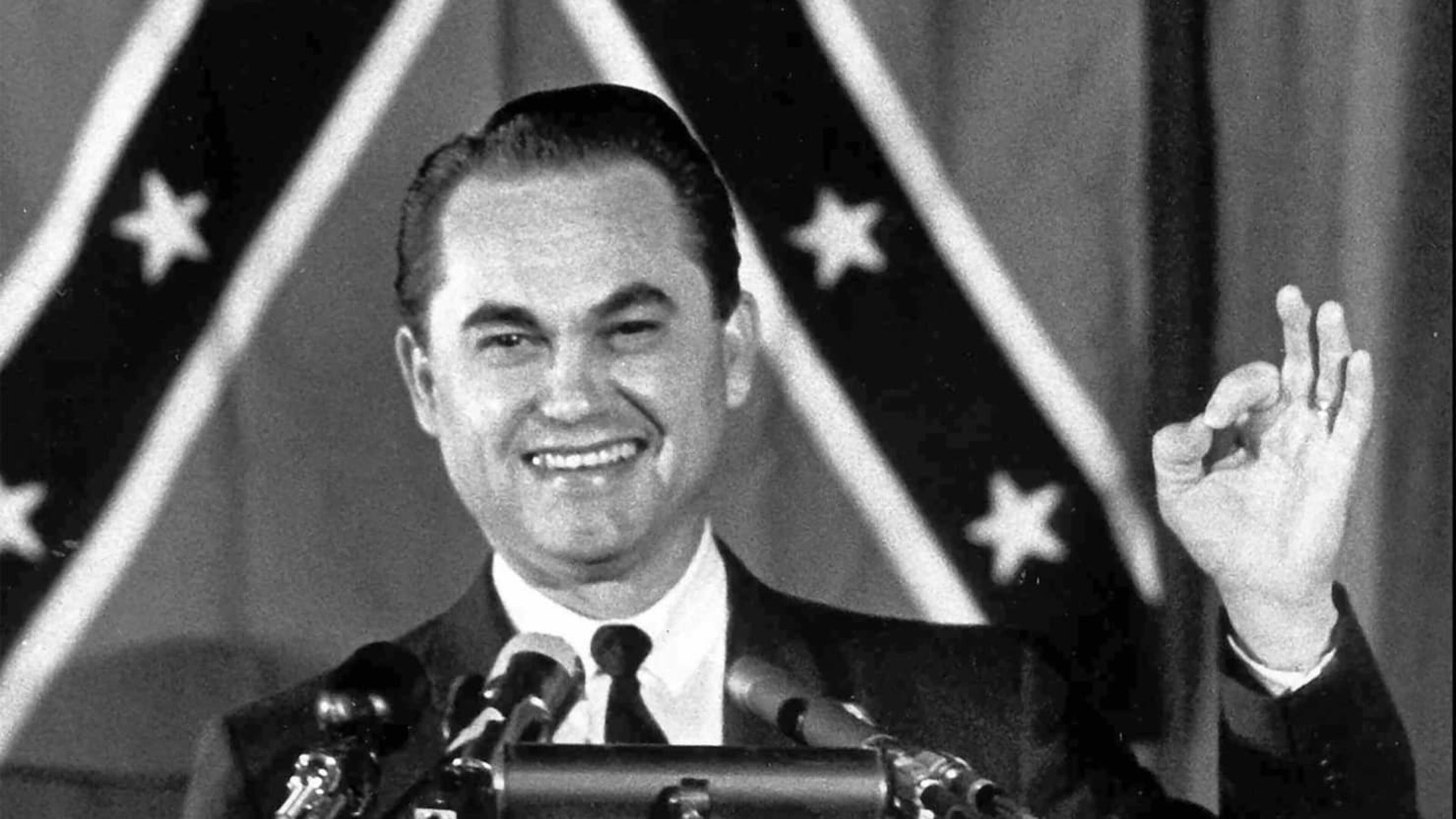

Lewis’ efforts eventually touched even former Alabama Gov. George Wallace, the segregationist who sent the state troopers who intimidated, tear-gassed and beat peaceful protesters at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In his later years, Wallace sought to apologize to the Black community. Lewis first met the repentant politician in 1979. He later recounted that he “had to forgive” Wallace because to do otherwise “would only perpetuate the evil system we sought to destroy.”

“The civil rights movement achieved its goals in the person of Mr. Wallace, because he grew to see that we as human beings are joined by a common bond,” Lewis wrote in The New York Times after Wallace’s death in 1998.

Lewis’ capacity to forgive also struck a cord with Wallace’s daughter, Peggy Wallace Kennedy.

Kennedy first became aware of Lewis on Bloody Sunday. She and her mother were watching the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg” on television when it was interrupted with footage of a young man in a tan trench coat being attacked by a state trooper.

She wouldn’t come face-to-face with Lewis until 2009, when she was invited to Selma to commemorate an anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

She said a turning point in her life came as she crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge holding Lewis’ hand.

“He was just so kind to me” Wallace told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “He gave me the strength and courage to find my voice that day where I’d not had a voice before.”

Kennedy has since authored a book that grapples with her father’s legacy and she has traveled the country speaking to groups about peace and reconciliation.

“I think our journey across that bridge was really a testament to change and redemption,” she said.

Familial bonds

Less public and maybe more painful for Lewis was a rift in his personal life that took more than a decade to repair.

He became estranged from his best friend, the civil rights leader and former Georgia legislator Julian Bond, following their bitter battle for a congressional seat.

The two traced their friendship back to spring 1960, to one of the first organizational meetings of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In the years after, Lewis and Bond would go to Braves games with their families and vacation together in places like Jamaica and Disney World. Lewis was even godfather to Bond’s son, Michael Julian Bond.

That changed in 1986, when both sought the same Atlanta-based U.S. House seat. Bond was backed by the city’s Black establishment and was the favorite. He came within three points of winning the primary outright, but Lewis managed to drag his old friend into a runoff.

Lewis got uncharacteristically negative on the campaign trail. He echoed another opponent’s call that Bond submit to a drug test, intimating Bond may have had something to hide, and suggested that Bond didn’t want to work hard. Lewis’ campaign slogan was “vote for the tugboat, not the showboat.”

In his memoir, Lewis said he was bothered by the political class’ assumption that Bond was a shoo-in for the job.

Lewis ultimately pulled off an upset, but the damage to their friendship was done.

“That was just awfully painful for me,” Bond said in a 2002 C-SPAN interview.

Time helped the hurt subside. The pair ran in the same circles, and at an event they approached one another, shook hands and talked through things, said Pam Horowitz, Bond’s second wife.

“It wasn’t set up ahead of time, and it wasn’t anything particularly noteworthy,” she said. “It was a thaw.”

In later years, Lewis would occasionally speak to participants of the civil rights tours Bond organized through the University of Virginia, but the friendship was never the same, said Horowitz.

Michael Julian Bond, now a member of the Atlanta City Council, called the fight between his father and godfather a “great American tragedy.”

“I hate that that (congressional) race kind of robbed America of its civil rights dynamic duo,” he said.

‘Right that wrong’

Some of the deepest impressions Lewis made were on people who weren’t yet alive during the civil rights struggle.

Kevin Murphy wasn’t born until a year after Lewis was knocked unconscious from a blow by a wooden Coca-Cola crate in 1961, after the Freedom Riders pulled into the Montgomery, Ala., bus station. But as the city’s police chief in 2013, Murphy wanted to issue an apology for the officers who declined to step in as a white mob descended on Lewis and his colleagues.

So when Lewis and other dignitaries assembled at Montgomery’s First Baptist Church to commemorate the events, Murphy walked to the microphone and offered Lewis what was long a symbol of oppression for many African Americans: his police badge. Murphy told Lewis he hoped it could serve as a token of reconciliation.

“I often said when I started going up through the ranks that if I had a chance, if I ever became police chief, that I was going to try to right that wrong,” said Murphy, now chief deputy sheriff for Montgomery County, Ala., in an interview. “A lot of my peers didn’t want to talk about it, didn’t want to face the truth.”

The two struck up a friendship. Lewis invited Murphy to the White House to meet President Barack Obama. They traveled to Ireland and Northern Ireland to talk with Catholics and Protestants about bridging the religious divide.

Murphy said he was awed by Lewis’ capacity to walk through the world with an open heart.

“You could just tell with everything he’d been through, he wasn’t a bitter man. He truly had tried to put a lot of what happened, the injustices, behind him,” he said.