Leon Eplan, 92, who planned Atlanta’s modern rise, dies

In recent years while cruising Atlanta’s streets, many of which bore his handprints, Leon Eplan sported a vanity license plate reading “PLAN.” This was less an homage to his surname and more an encapsulation of a lifelong ideology and obsession.

Eplan was not Atlanta’s first seminal planner. But from around 1960 to years beyond the 1996 Olympics, he was a visionary who, like the city he loved so much, ceaselessly reinvented himself.

In the early 1970s he was the chief planning consultant for designing MARTA, promoting the idea that most transit stations — 27 of the original 40 were within city limits — would become centers for dense development.

In the 1970s, as Mayor Maynard Jackson’s Commissioner of Budget and Planning, he helped implement comprehensive planning that included residents’ input by setting up the city’s Neighborhood Planning Units.

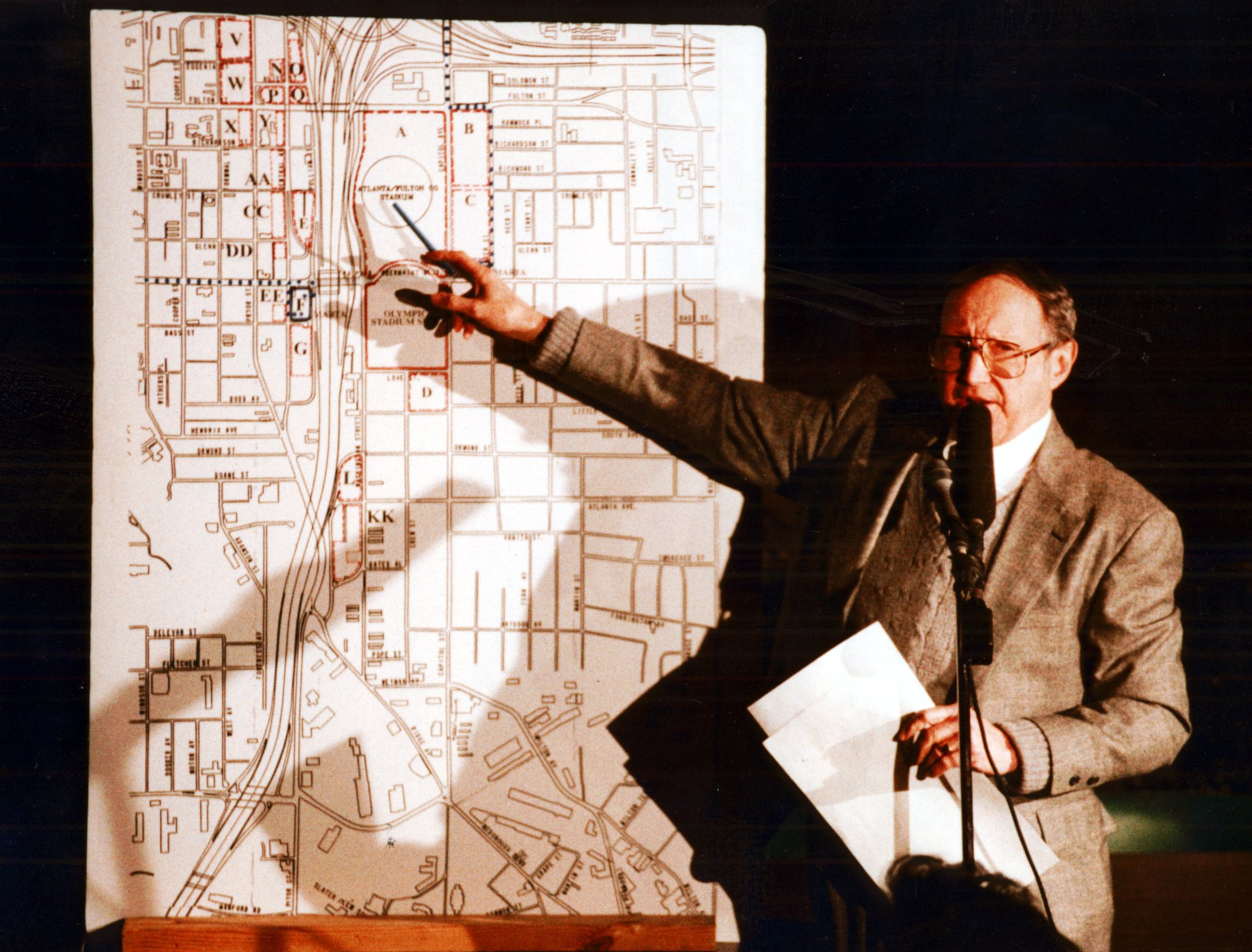

In the early 1990s, Jackson chose him as Commissioner for Planning and Development for the Olympics, with a long view that the games would instigate rebirth for a city that had lost 100,000 residents between 1960 and 1990.

In 1991, he would help broker a compromise leading to the development of the John Lewis Freedom Parkway. And he held several academic positions over the years.

Leon Samuel Eplan, 92, died April 15 of complications from colon cancer 11 weeks after losing his wife of 62 years, Madalyne Eplan. He was buried the next day during a private service.

“Sometimes you don’t see the fruits of your labor until 30 or 40 years later, or maybe not even in your lifetime,” said Eplan’s friend and Atlanta Community Food Bank founder Bill Bolling. “You look at something like the planned developments around MARTA stations and you can see that we are just now beginning to realize Leon’s vision.”

Eplan was born November 24, 1928, in Jacksonville, Florida, where his father ran a business for a short while. The family moved to Atlanta when Leon was 3 years old. His grandfather, a peddler and baker, had arrived in Atlanta in 1881 from Russia and settled in the Summerhill neighborhood at a spot roughly where decades later Chipper Jones played third base at Turner Field.

Eplan’s father became a lawyer in Atlanta.

Leon earned an undergraduate degree, two master’s and a Ph.D., the latter from the London School of Economics, where at 5 feet 5 inches tall he captained the University of London’s basketball team. He held several positions before returning to Atlanta in 1960.

With Eric Hill Associates, he did the feasibility study for the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, a project he later regretted. Eplan told AJC columnist Bill Torpy in 2015 that no consideration was given to the future impact on the surrounding environs when a portion of his grandfather’s neighborhood was razed.

“We just threw people out,” Eplan said. “We did some terrible things. It was my job.”

He spent the rest of his career making up for it, particularly while toiling on the Olympics. Both he and Jackson wanted a successful games, but more important to Eplan, he once explained, was to “take all that energy, emotion and money and . . . rebuild the city for the 21st century.”

By 2000 residents and businesses began moving back to Atlanta.

Next to the Olympics, his most enduring achievement was consulting on MARTA’s evolution in the early 1970s. He insisted that a station get placed inside the airport and another beneath Decatur’s square in hopes of stimulating that city’s then-dormant downtown.

“I was always fighting engineers,” he said. “They thought it was a system to move from this spot to that spot. I wanted to use transit to create a certain kind of city with little village centers . . . as an antidote to sprawl.”

Elliott Levitas, an attorney and one of Eplan’s closest friends, said Eplan could be uncompromising.

“That’s one reason developers and engineers didn’t get along with him. There was no changing his mind. Instead of finding a middle ground he would stake out his position. Though he was generally on the right side of issues.”

Architect and friend Jerry Cooper said: “I wish he was still here to argue with. We were friends for 80 years and it goes by in a blink of the eye.”

Leon Eplan is survived by his children Elise Eplan (Bob Marcovitch), Jana Eplan (Craig Frankel) and Harlan Eplan (Jen Denbo), along with six grandchildren.