A 15-year-old Black girl held in juvenile detention for more than two months for not completing online schoolwork will remain locked up after a Michigan judge this week denied her request for an early release, according to reports.

“You’re exactly where you’re supposed to be,” Oakland County Judge Mary Ellen Brennan told the girl during the Monday hearing, according to CBS News. “You’re blooming there, but there’s more work to be done.”

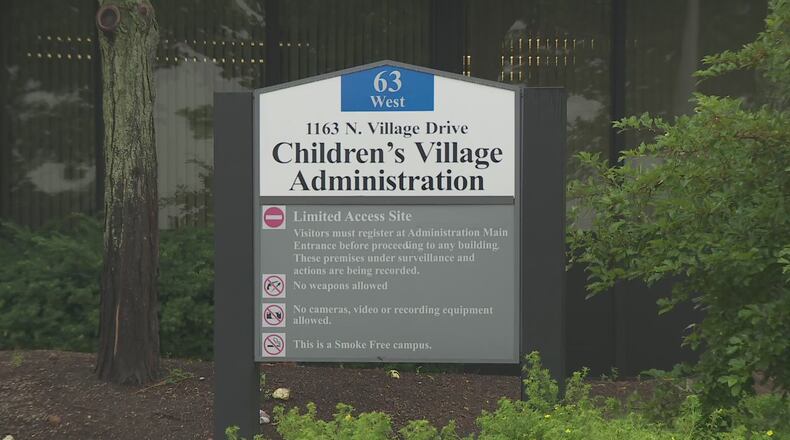

The girl, identified as Grace in a recent investigative report by ProPublica, has been jailed since May 15 and will now likely have to remain in the Children’s Village juvenile detention center in suburban Detroit for about 3½ more months, CBS reported.

»PREVIOUS COVERAGE: Girl, 15, sentenced to juvenile lockup for not doing schoolwork

She initially got into trouble in April after a physical fight with her mother, Charisse, and for stealing another student’s property. Grace was subsequently charged with assault and theft. After an April 21 hearing, she was placed on probation, during which time the homework infraction occurred.

At the May 15 sentencing, Brennan called Grace a threat to the community and sent her to the detention center, although the teen had not committed another crime.

The girl has been locked up since.

She was ordered again in early June to remain in the facility pending the hearing to review the case, which has sparked widespread criticism among children’s advocates. During the weekend, dozens of people gathered in front of the detention center to protest.

On Monday, Brennan continued to maintain that Grace was a danger to her mother.

“This is not an easy decision to make,” Brennan said. “How many times does she get to jump her mom before you think that she’s a threat of harm to her mom? How many times?”

After the hearing, Grace reportedly cried in her mother’s arms, CBS reported.

Jason Smith, a director with the Michigan Center for Youth Justice, said Grace needs support, not punishment.

“It’s frustrating that instead of trying to figure out a way that she can get additional support ... the first step that the judge took was to incarcerate her,” Smith said, according to CBS.

In Brennan’s May decision, she found Grace “guilty on failure to submit to any schoolwork and getting up for school” and called Grace a “threat to (the) community,” citing the assault and theft charges that led to her probation.

“She hasn’t fulfilled the expectation with regard to school performance,” Brennan reportedly said as she sentenced Grace. “I told her she was on thin ice, and I told her that I was going to hold her to the letter, to the order, of the probation.”

The tough sentence was handed down as Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer encouraged the state’s juvenile judges to send children home due to the pandemic.

In March, Whitmer issued an executive order that temporarily suspended the confinement of juveniles who violate probation unless directed by a court order. The order also recommended eliminating any form of detention or residential placement unless a young person posed a “substantial and immediate safety risk to others,” ProPublica reported. The order was extended until late May.

The Michigan Supreme Court also ordered juvenile judges to determine which young offenders could be returned home.

During the sentencing in the Oakland County Family Court Division, caseworkers also recommended mental health and anger management treatment. The prosecutor agreed, and Grace’s court-appointed attorney asked for probation because she had committed no new offenses and because of the risk of coronavirus.

Instead, Grace was led from the courtroom in handcuffs.

ProPublica, an independent nonprofit investigative news outlet in New York City, used middle names for the teenager and her mother in the report to protect their identities.

Brennan declined to comment.

By mid-June, Grace had been in the lockup for more than a month when her mother visited.

At the time, Charisse said she wasn’t allowed in to see Grace, and officials sent the mother away with a shopping bag full of clothes and toiletries she delivered to her teen daughter days earlier. The items had been rejected because they violated facility rules, according to ProPublica.

On the drive home after she left the facility, Charisse said she pulled into a nearby parking lot and cried.

“It just doesn’t make any sense,” she told ProPublica. “Every day I go to bed thinking, and wake up thinking, ‘How is this a better situation for her?’”

ProPublica was unable to determine how many other children might be in a similar situation as Grace because of the confidentiality that shrouds juvenile cases.

Attorneys and civil rights advocates told ProPublica the judge’s ruling disregarded their calls for leniency and failed to prioritize the health and safety of children amid an ongoing national health crisis.

They were also unaware of any other recent case nationally in which a child had been detained for failing to meet academic standards.

There has also been a steep decline in juvenile detentions nationwide in recent months due to the outbreak, according to the report.

“In many places, juvenile courts have attempted to keep children out of detention except in the most serious cases, and they have worked to release those who were already there,” ProPublica reported, citing experts.

ProPublica cited several other school districts in Los Angeles, Minneapolis and Chicago that have documented tens of thousands of students who failed to log in or complete coursework, but without the consequence of juvenile detention.

Legal experts are now pointing to the case as a quintessential example of systemic racism.

Grace’s school, in the city’s predominantly white Beverly Hills community, moved to remote learning on April 15 as schools across the nation locked down for the remainder of the academic year because of the pandemic.

Grace also has an educational disability, ADHD, and without the structure of the classroom she struggled to stay motivated and found herself often distracted, ProPublica reported.

“I just needed time to adjust to the schedule that my mom had prepared for me,” she said on the day she was sentenced to detention.

“Who can even be a good student right now?” said Ricky Watson Jr., executive director of the National Juvenile Justice Network, according to ProPublica. “Unless there is an urgent need, I don’t understand why you would be sending a kid to any facility right now and taking them away from their families with all that we are dealing with right now.”

Defense lawyers argued similarly for Grace during Monday’s hearing, saying many students struggled with virtual learning.

“The struggle of a student experiencing disabilities in time of COVID — it was recognized by the school,” said Saima Khalil, according to CBS. “There is no point where my client or the mother was saying, yeah, take my kid away from me and throw her in detention,” Khalil said.

The court issued a statement that defended Brennan’s Monday ruling, saying “these decisions do not reflect one event or one bit of information, but rather an extensive review of a juvenile’s case file.”

ProPublica found that a disproportionate percentage of Black youth who live in the same county as Grace are also caught in the juvenile justice system.

Grace’s mother has made at least three other recent visits to the facility, ProPublica reported.

In early June, she saw her daughter on screen as she walked into a court hearing handcuffed and with her ankles shackled.

“For us and our culture, that for me was the knife stuck in my stomach and turning,” Charisse told ProPublica. “That is our history, being shackled. And she didn’t deserve that.”

During the proceeding, Grace and her mother pleaded with the judge to return her home. “I will be respectful and obedient to my mom and all other people with authority,” Grace said. “I beg for your mercy to return me home to my mom and my responsibilities.”

The judge, however, ruled that Grace should stay at the Children’s Village not as punishment but to get treatment and services.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured