Why did Atlanta water crisis drag on? These failing parts went undetected

The water was ferocious.

It blasted through a layer of asphalt as it ripped out from the earth. It shot a geyser so high into the air it soaked the awning of a bar next door. It let out a roar like a waterfall and opened a gaping hole in the core of Atlanta’s Midtown.

The gusher unleashed in late May became an unmistakable symbol of Atlanta’s troubled infrastructure. It was blamed on an aging system of water pipes that springs hundreds of leaks each year, prompting the mayor to float billions of dollars in repairs.

But the fiasco was exacerbated by another critical shortcoming that still threatens the city’s water system, an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found. Atlanta failed to maintain the thousands of shut-off valves buried below the city, and in a moment of crisis, several crucial valves didn’t work, according to interviews and a review of the city’s water records, emails and internal data.

The failed valves let water gush out unabated for days, the AJC’s review found, prolonging an embarrassing episode that disrupted one of America’s busiest commercial districts for nearly a week.

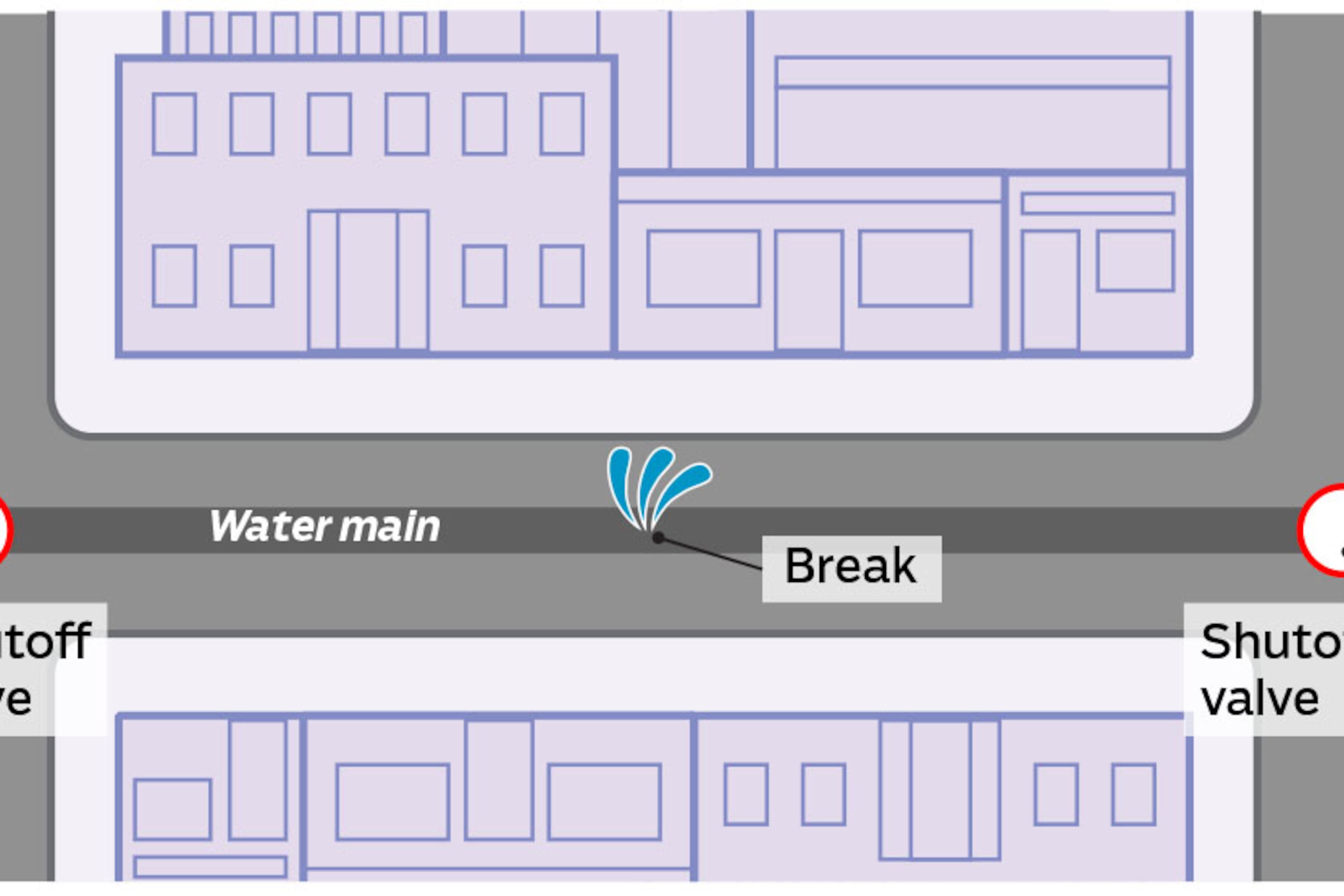

Think of shut-off valves like spigots controlling how Atlanta’s drinking water flows through a network roughly 2,900 miles long. They are the tools cities use to contain the damage when a water main bursts.

“When you have a break, there’s an upstream valve and a downstream valve, and you’ve got to know where they are and you’ve got to be able to close both of them,” said Councilman Howard Shook, a longtime member of the council’s utilities committee. If they aren’t tested regularly, Shook said, “then you’ve got big problems. Obviously, that’s where we are.”

After the geyser erupted May 31, some valves froze up or wouldn’t stay closed, like faucets stuck open, according to internal records and an interview with the city’s top water official. Others had been paved over, hidden from view when workers went looking for them.

Repair crews waited all weekend for the city to regain control of the system, unable to even inspect the pipe with water blasting out of it.

Mayor Andre Dickens’ Office of Emergency Preparedness summarized the conundrum the day after the break: “Water shooting 5 feet into the air,” officials wrote in notes obtained by the AJC through an open-records request. “No end in sight, as the issue with the main has not yet been identified.”

‘Discouraging and baffling’

Atlanta’s water system was having a bad day before the pipe broke in Midtown. Hours earlier, a major supply line burst on the edge of Vine City, and while crews successfully isolated the break, thousands of residents lost water in the process.

Atlantans were beginning to learn that one faulty pipe could cause disruptions across the city.

But the broken line in Midtown showed that failing valves threaten widespread disruptions, too, a risk that still looms over the city. While Atlanta officials acknowledge they have a problem, they are only just beginning to address it.

The AJC, which filed nearly a dozen open-records requests for this story, sought a clear accounting of how the city maintained and tested its shut-off valves, but city officials could not provide one. They don’t know, for instance, how frequently city crews were testing the valves because of years of sloppy, inconsistent record-keeping, officials said in an interview.

Regularly opening and closing valves — exercising them, as the industry calls the practice — is a crucial component of maintaining a water system. It prevents corrosion from jamming them up and helps utilities spot failing equipment early.

Why water valves are so important

Cities install shutoff valves along water mains so they can cut off the flow if they need to. If a pipe breaks, for example, crews can’t make repairs with water gushing out. Valves help them get to work.

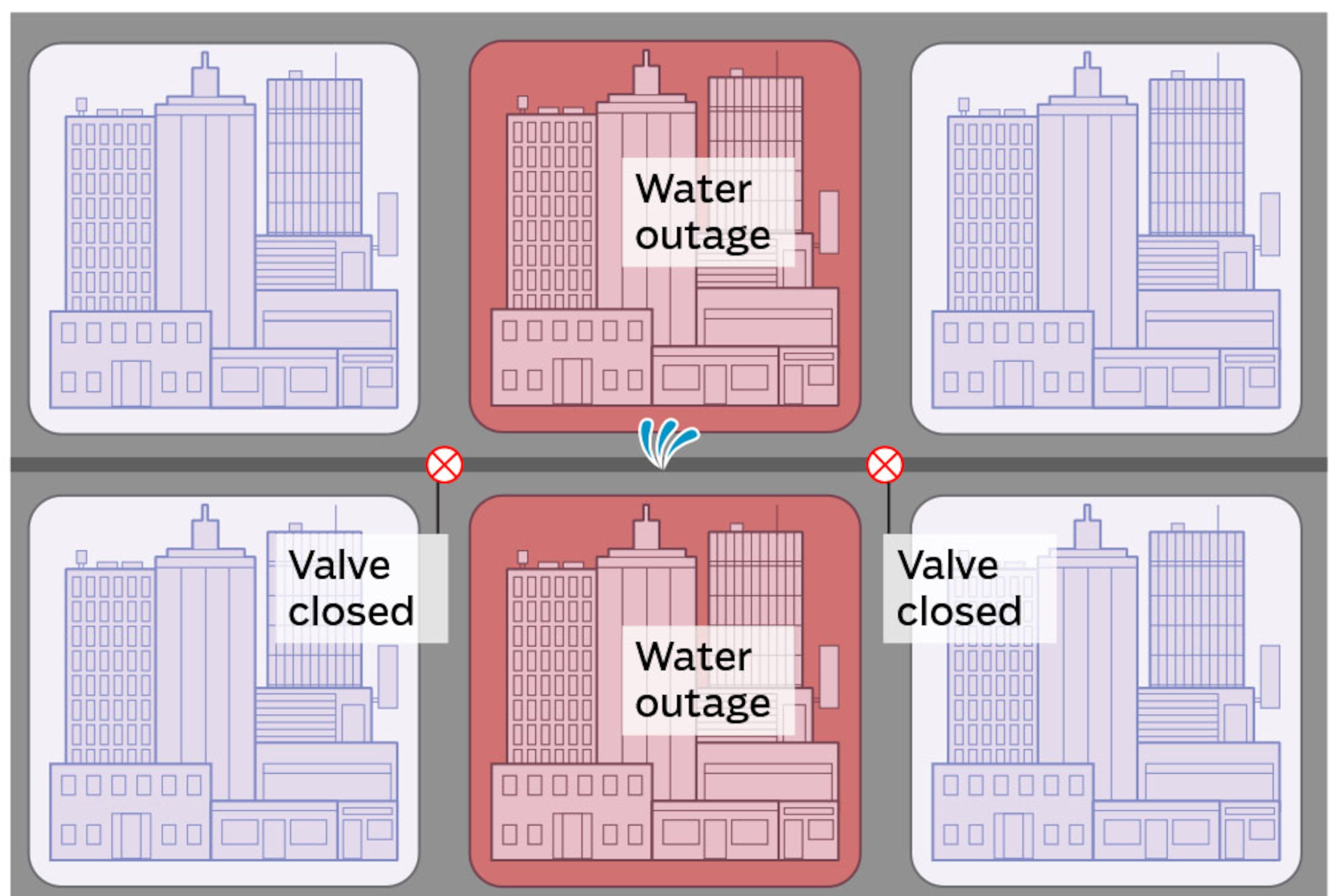

Working properly, valves limit a broken pipe’s impact on the rest of the city by limiting water outages to the area right next to the problem.

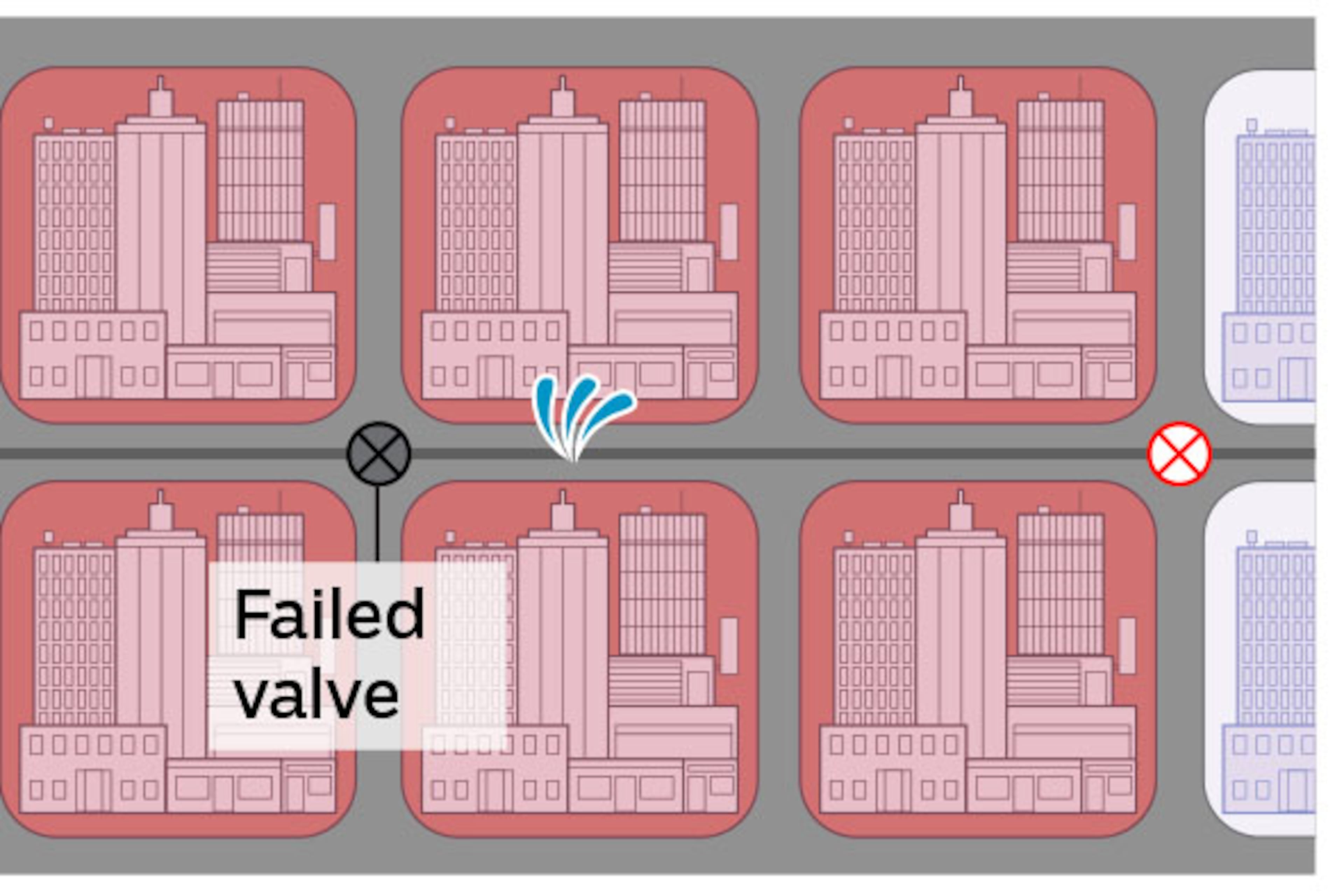

When a valve doesn’t work, the disruption spreads. To isolate the pipe, crews will have to cut off water to even more of the city.

In dense areas like Midtown, the impact of broken valves is even greater, spreading through a web of interconnected pipes and multiplying the number of people losing water.

CREDIT: Thad Moore & Pete Corson/AJC

Ensuring that valves will work when they’re needed is the “bread and butter” of running a water utility, Shook said. Hundreds of water mains break each year in Atlanta, though most are small lines that have limited impact.

Meanwhile, the city’s approach to the valves responsible for mitigating the impact of breaks has been “discouraging and baffling,” Shook said in response to the AJC’s findings.

In response to an open-records request, the city provided data indicating Atlanta’s Department of Watershed Management was testing valves at a pace so slow it would have taken several decades to reach them all. But when city officials were pressed on the anemic rate, they said the data was unreliable.

Workers didn’t always write down which valves they inspected, officials said. Even when they did, the officials said, the results weren’t consistently entered into the department’s database.

In an interview, watershed commissioner Al Wiggins Jr., who Dickens appointed to run the department in May, said his staff told him valves were tested twice a year. But he conceded the agency, which supplies water to more than 1 million people, has no evidence showing the tests actually occurred. After the Midtown break, multiple valves malfunctioned, he said.

“We do not have any records to support that these valves were exercised on a semiannual basis,” Wiggins said.

What city officials can say for certain, Atlanta Chief Strategy Officer Peter Aman said, is that they “need to do a much better job.”

‘Not working’

Across the street from the Midtown geyser, Sam Weyman grew increasingly frustrated as days ticked past.

It wasn’t such a big deal that his restaurant Steamhouse Lounge had to close early Friday night, May 31, or even that water started streaming into the basement. A night’s lost business was manageable, and the flooding abated when his staff set out bags of dirty linens like a makeshift dam.

But whenever he stopped by that weekend, nothing seemed to be happening at the corner of West Peachtree and 11th streets. The geyser was throwing up chunks of pavement “like a volcano,” he said, and the sinkhole gradually widened. All weekend, workers seemed few and far between. He started taking videos of the gushing water and what he saw around it.

“It’s Sunday afternoon,” he narrated in one recording on June 2. “There’s not a soul here. Not a soul working or even standing around.”

“Oh look,” he remarked on another video a few minutes later. “There’s a guy in a hardhat. One guy in a hardhat.”

The damage to his business mounted with the delays. When the water crisis finally ended after six days, Steamhouse had lost about $70,000 in sales and enough seafood to supply its weekly Oyster Day special, Weyman said.

Yet there was little for workers to do in the days after the pipe burst. The break couldn’t be inspected with water shooting out, and the shut-off valves weren’t stopping it. The next evening, the city’s joint operations center was informed that “many of the valves used to shut off service to an area are not working,” according to notes from the city’s emergency meetings.

To make matters worse, the department later discovered that the valve closest to the break was directly beneath it, Wiggins said. It would have been too dangerous to get to even if they’d known it was there.

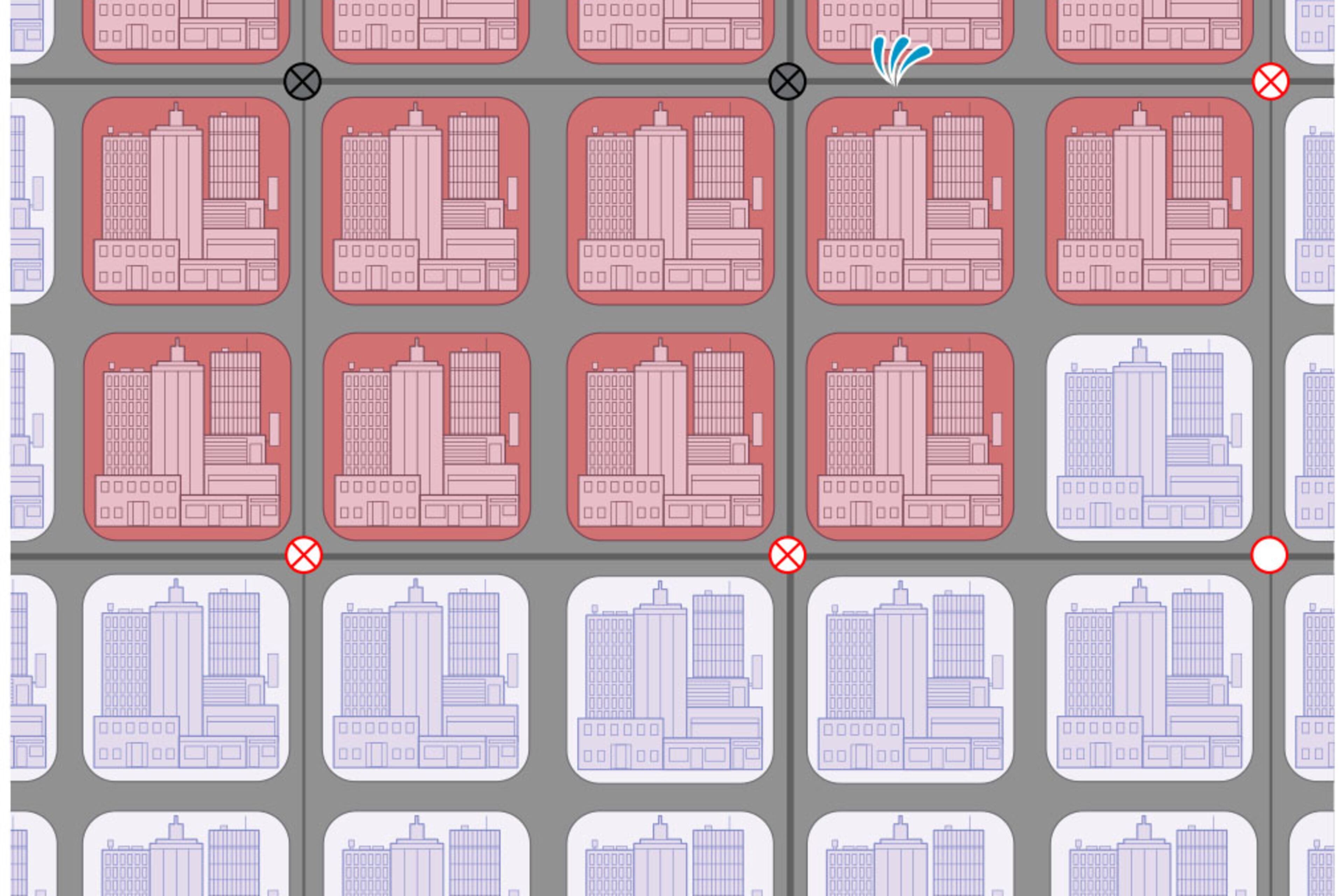

But the problems were not limited to the valves right next to the break. City records show crews followed one water main across the Downtown Connector to Georgia Tech and toward the city’s largest water treatment plant, apparently looking for places to stanch the flow. All along the way, they found problem valves.

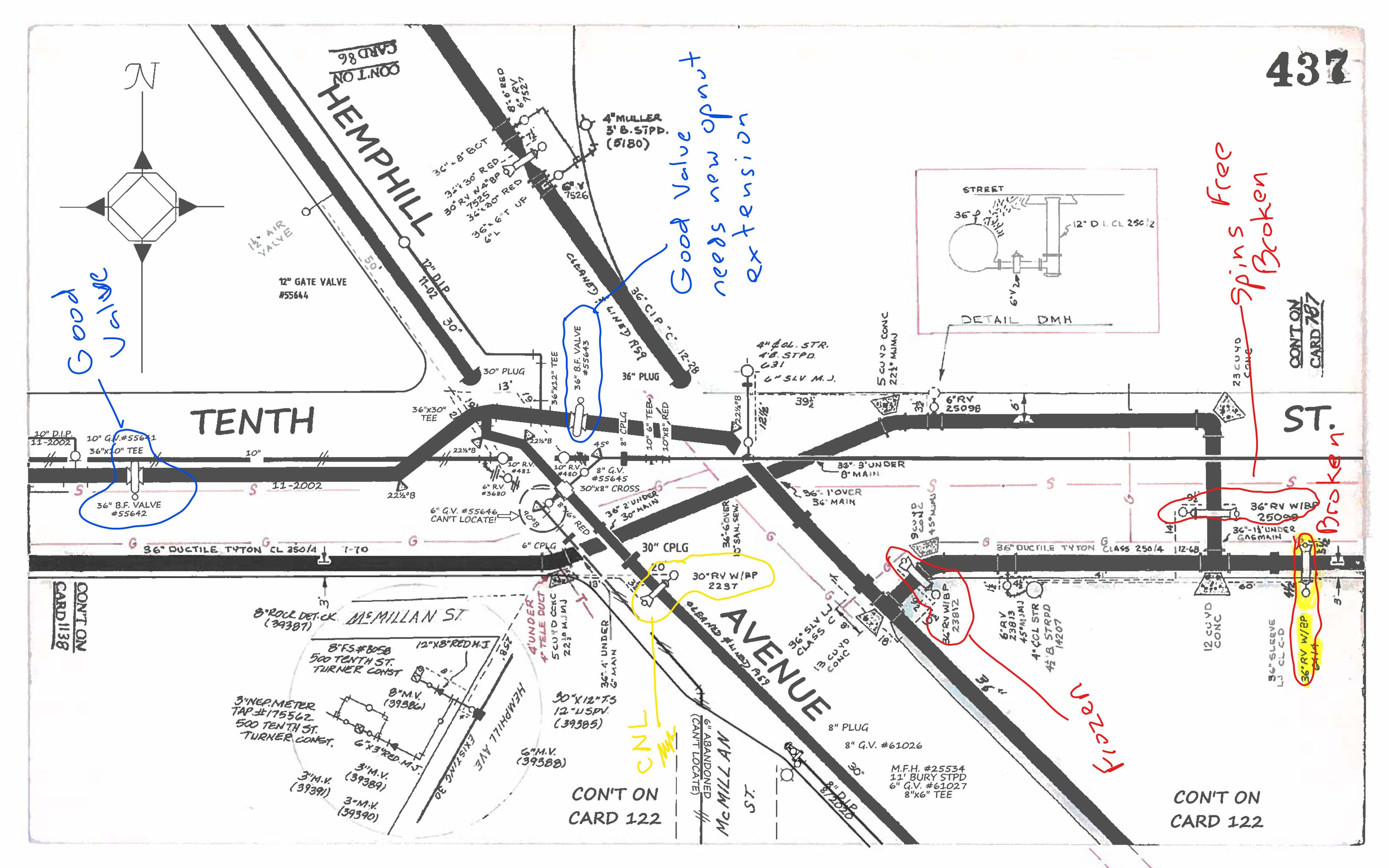

A valve maintenance supervisor marked up a map of the line, which is one of Atlanta’s arteries, and noted the issues, according to an email obtained by the AJC. At one street corner, valves were hidden, “frozen” and “broken.” At another point, she drew a red X through a valve that was spinning freely. Near the break, she noted a valve “unable to operate” and another “closed — but not holding.”

In a matter of days, the city was discovering problems across Atlanta that had been years in the making.

Untested

If the Department of Watershed Management tested any of the failed valves in the years leading up to the Midtown break, its crews didn’t document their results.

The most recent tests were logged in the department’s database in October 2017. The department did not respond to questions about whether they’d been inspected more recently.

The department also did not answer specific questions about how frequently it intends to test its valves going forward. But other utilities in the region say they aim to check their valves every few years.

A spokeswoman for the Clayton County Water Authority says it tries to test its valves every three years. Gwinnett County said it checks the valves on its largest lines annually. Cobb and DeKalb counties have hired contractors to systematically check every valve in their systems in recent years.

If Atlanta hadn’t tested the failed valves since 2017, “that’s a major no-no,” said Kanwal Oberoi, a former chair of the American Water Works Association’s water distribution standards-writing committee.

Oberoi co-wrote the industry’s best practices for operating valves and now oversees water distribution infrastructure for the Charleston Water System in South Carolina. There, he says, each valve is tested every two years. Since the program was implemented, the more than 40,000 valves in Charleston’s system have failed “very rarely,” he said.

“A lot of utilities don’t do that because it’s out of sight, out of mind,” Oberoi said, adding: “It doesn’t work because nobody checked on the darn thing.”

When a valve fails, the consequences of a busted water pipe quickly multiply, said Jim Poff, who ran operations at the Clayton County Water Authority before joining the staff of the Georgia Association of Water Professionals. To isolate the break, crews have to look for working valves farther away, cutting off water to a larger area.

That was the scenario Atlanta faced in Midtown, Wiggins said. To stop the flow with the city’s working valves, he said, the outages would have stretched into Buckhead.

“We weren’t comfortable with any of the scenarios,” Wiggins said, adding: “There were several, but we didn’t like any of them.”

The only other option was to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on special temporary valves and install them right next to the break so fewer people would lose water. The plan would require waiting for the valves to arrive from out-of-state, and customers from downtown Atlanta to East Lake would have to boil their water in the meantime.

The city decided it was worth the wait.

‘What we had’

Doug Pugh is in the business of getting the water to shut off.

From its home base in Alabama, his company, Water Services Group, installs temporary valves called line stops throughout the Southeast, often in emergencies. Atlanta officials called him the day after the Midtown pipe broke in just such a bind. They wanted to fix the break without shutting off water in the core of the city.

The break would prove to be an especially complicated job. It sat near the intersection of two major lines, and they would both need to be blocked off. The packing list in Alabama kept changing as Atlanta’s crews determined what they needed. After they arrived in the wee hours of the morning more than a day into the fiasco, Pugh’s team discovered one of the valves they loaded in the chaos was the wrong size. Atlanta police and the Georgia State Patrol would ultimately escort its replacement through the Downtown Connector.

Even then, water was moving through the pipes too fast to install the line stops, Pugh said. To slow it, he said, the Department of Watershed Management eventually turned off pumps at the city’s main water treatment plant off Howell Mill Road, which provides almost half the city’s water.

The flow was still so strong that one of Pugh’s line stops got stuck open, apparently wedged on something inside the pipe. Though they had blocked most of the pipe — maybe even 90% of it, he estimated — water continued to gush out.

“We had what we had at that point,” he said.

Workers had no choice but to start the multiday process of making repairs with water pouring out, Pugh said. For all its efforts, he said, the city never did get the water to shut off.

‘Doing much more’

The delays added pressure to a city already under siege.

As the crisis extended well into the first week in June, residents grilled elected officials about the lack of updates the city provided early on. Property managers and tourists emailed the city to vent their frustrations and ask for updates about a civic headache that didn’t seem to abate. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency asked for a progress report to share with “the top levels of federal government.”

The episode immediately prompted calls for dramatic changes to the city’s aging water system.

Before the week was out, Dickens floated a plan to spend billions of dollars on infrastructure for a long-term overhaul. He formed a blue-ribbon committee to review Atlanta’s problems, and the city asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to undertake a multiyear study as well.

City officials told the AJC in September the shut-off valves would be included in those reviews.

“Clearly, this is an area of concern of ours and something we’ll be doing much more of and paying much more attention to,” said Aman, the chief strategy officer.

Aman and Wiggins, the watershed commissioner, said the Department of Watershed Management has already begun changing its approach to the valves in response to the problems in May and June.

Crews have started assessing valves in sensitive areas, like those near hospitals, jails and senior homes, Wiggins said. To ensure valve covers are not paved over, he said the city has designated a team to check behind road crews.

And while they can’t account for the city’s past valve tests, they said the department would keep better records going forward.

But their most comprehensive plan — a systemwide assessment of all the city’s shut-off valves — is still in the planning stages. Wiggins said the city would soon solicit bids for the job, which would cover more than 60,000 pieces of equipment buried below the city.

For now, however, Atlanta’s is a system at risk. When pipes break, the city is still learning whether it can turn off the water.

Our Reporting

After a pair of water main breaks disrupted life for thousands of Atlantans in May and June, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution sought to find out why these problems became so severe and lasted so long.

Reporter Thad Moore filed nearly a dozen open records requests and reviewed data, internal meeting notes, emails and other records of city officials to learn more about how the city responded to the emergency and how the Atlanta Department of Watershed Management maintained its system.

Notes from the city’s emergency meetings identified valve failures as a key issue, and that prompted additional questions and records requests. The reporting included reviewing the watershed department’s internal communications, equipment inventory and valve exercising records to determine which valves failed and when they had last been tested. The AJC also requested a copy of the department’s plan for exercising valves, but the department’s records custodian said the agency did not have a written plan.

In a later interview, Commissioner Al Wiggins Jr. said his department’s testing records were incomplete and the city didn’t know how frequently valves were exercised prior to May. He and an official from Mayor Andre Dickens’ office committed to overhauling the city’s approach to exercising valves to ensure they function properly when water pipes break.