By her sixth month as the top lawyer for Georgia’s public health agency, Jennifer Dalton had objected to a no-bid contract for a well-connected lobbyist’s client. She had refused to give free legal advice to two private citizens — the lobbyist’s parents. And she had released public records that led to a critical news story about Gov. Brian Kemp.

So when Dalton was summoned to a conference room at the Department of Public Health on a Tuesday morning in March 2021, she wasn’t surprised to learn she was being fired. What she didn’t see coming was what happened next.

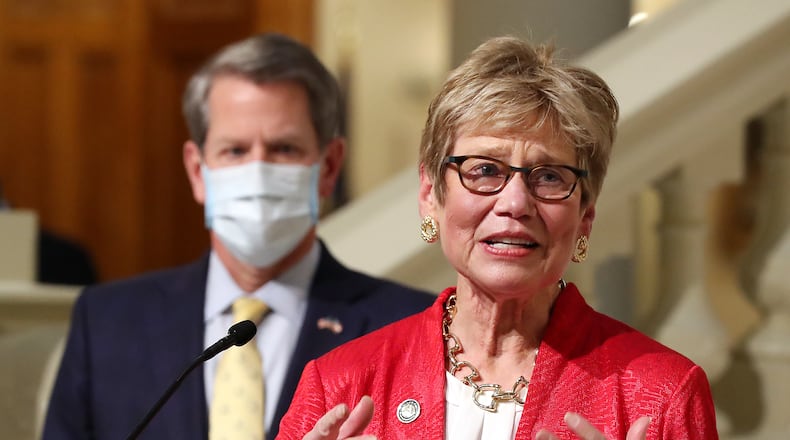

Two state troopers and two other men removed Dalton from the building, parading her past her stunned staff as if she had been caught stealing. “It was humiliating,” Dalton said. “I’m not a scary person. I am 5′8″. I was almost 61 years old.”

contributed

contributed

More than a year later, though, Dalton feels vindicated. The state recently agreed to pay her $750,000 to settle a complaint in which she alleged she was fired for objecting to what she called “potential violations of state and federal law” as the health agency struggled to contain the coronavirus pandemic.

“I won,” Dalton said in an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, in her first public comments on the matter. “And they were wrong. I worked too hard for that to happen.”

In settlement documents, state officials deny Dalton’s allegations of malfeasance and contend the payment is not an admission of wrongdoing.

Dr. Kathleen Toomey, the state public health commissioner who fired Dalton, declined to comment. Toomey’s spokeswoman, Nancy Nydam, released a statement that omitted Dalton’s name, referring to her only as “this disgruntled ex-employee.”

“Notwithstanding,” Nydam wrote, “the matter has been settled and DPH will continue to focus on its critical mission.”

The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Dalton’s complaint shed light on the chaos that marked the state government’s response to the coronavirus. Officials scrambled to set up testing sites and to procure personal protective equipment and other materials, sometimes spending millions of dollars with little oversight.

Dalton took the job in October 2020, after 27 years with other state agencies, mostly at the attorney general’s office. At Public Health’s headquarters in downtown Atlanta, Dalton’s office was just a few steps from Toomey’s and, she said, they consulted frequently. The agency’s legal division had experienced substantial turnover and had gone several months without a permanent leader. Even without the pandemic, the workload would have been intense.

Dalton began clearing a backlog of public records requests, most of which concerned the agency’s pandemic response, while also helping to draft vaccination protocols, contracts for temporary workers and contact-tracing policies for county health departments.

“It was all I did,” she said, “24/7.”

A series of internal conflicts, she said, quickly strained her working relationship with Toomey.

Four days after Dalton joined the agency, she expressed concerns about a plan to send Toomey’s pandemic-related emails to the governor’s office. She warned that sharing the emails might violate federal law if they contained personal medical information about individuals with COVID-19. But Toomey ordered her to share the emails, anyway, Dalton said, and later instructed her not to re-examine the messages for possible violations.

The tension with Toomey escalated, Dalton said, when the commissioner asked her to prepare a legal opinion about a private matter for Abit Massey, president emeritus of the Georgia Poultry Association, and his wife, Kayanne. The Masseys apparently are friends of Toomey’s. Their son, Lewis Massey, is a former Georgia secretary of state and a prominent lobbyist in the state Capitol.

State law prohibits lawyers in the attorney general’s office from any private legal practice. Whether that statute applies to lawyers in other agencies is not clear. Regardless, Dalton said, “we do not provide advice to private citizens.”

Dalton instead compiled a list of websites that might answer the Masseys’ question.

“It was not what she wanted,” Dalton said of Toomey, and the commissioner sent her an email instructing her to be more responsive to future assignments.

A few weeks later, Dalton received a draft of a contract with one of Lewis Massey’s clients, Maximus Inc., to operate a vaccination call center. The deal had been in the works for several weeks but had not been put out for competitive bids — “an extraordinary step,” Dalton said.

In a Saturday morning telephone call in late February 2021, Dalton said she told an aide to Toomey that bidding would ensure fairness. She told the aide she would call Toomey to make the same point. Instead, Toomey called her.

“She said, ‘Get it done,’” Dalton said. “She was not interested in talking about the bidding process.”

Lewis Massey has denied impropriety either in the contract or in the matter involving his parents.

The final clash between Dalton and Toomey concerned a May 2020 request by the Journal-Constitution to review emails between the commissioner and the governor’s office during the first months of the pandemic. The request sat dormant for months before Dalton released about 15,000 emails in January 2021 after the newspaper threatened legal action.

Shortly after a reporter contacted Public Health and the governor’s office for comment for a possible story, Toomey called Dalton at home, demanding to review the emails herself.

“She said, ‘I need to see those records today,’” Dalton said.

The story published online on March 26, a Thursday. Citing the emails, it reported that Kemp’s aides had largely dictated Toomey’s public statements about the coronavirus and that the state had withheld information showing the pandemic was worsening as Kemp relaxed virus-control measures.

Already, Dalton said, David Dove, the top lawyer on the governor’s staff, had called her in to suggest she resign and seek a part-time position with the state agency that regulates construction of medical facilities. Dalton, who did not report to Dove, rejected his suggestion.

“I was prepared every day for that to be my last day,” Dalton said.

On March 30, a human resources official asked Dalton to come with him to a conference room. Toomey was already there, seated at a long table.

“She told me I was terminated,” Dalton said. “She said I did not have the right cadence. That was it.”

Getting a new job has been difficult, Dalton said, because if potential employers type her name into Google, news stories about her dismissal appear at the top of the search results.

Now she hopes a new result will pop up — the story of her vindication.

About our reporting

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported in July 2021 that Jennifer Dalton, general counsel at the Georgia Department of Public Health, had been fired shortly after the newspaper published a story based on documents she had released under the state Open Records Act in January of that year. Before Dalton joined the agency, it had suspended its compliance with the records law because of the coronavirus emergency. or the duration of the coronavirus emergency.

About the Author