One robbed a bank in Douglasville at the age of 16 and watched it turn into a comedy of errors when a dye pack mixed in with the cash exploded as soon as he reached the parking lot.

Another was just 14 when he joined two older teens in robbing delivery drivers in DeKalb County of cash, pizzas and Chinese food, threatening them with a broken gun.

Yet another was 26 and working at a Publix warehouse when he and a co-worker went on a crime spree in Gwinnett County that included a home invasion and two armed robberies. They were caught when police pulled them over for speeding and noticed liquor bottles, including pour spouts, from the Applebee’s they’d just robbed.

Arthur Lee Cofield Jr., Nathan Weekes and Ryan Brandt received lengthy sentences in the Georgia Department of Corrections for brazen but amateurish criminal attempts to get easy money. When they arrived, they weren’t notable criminals, murderers or gang leaders. But in prison, the three were transformed into allegedly powerful crime lords who, with the help of corrupt prison employees, built lucrative criminal enterprises that orchestrated violent attacks that occurred outside the walls.

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution examination of their stories, including new reporting on their past conduct, demonstrates how Georgia’s prisons aren’t just failing to reform people. They are allowing prisoners to keep offending — often for years and sometimes in deadly ways — while they’re behind bars.

Cofield was sentenced to 14 years in prison for the bungled bank robbery. Now he’s known as the astonishingly adept scammer who, from inside Georgia’s most secure facility, stole $11 million from the Charles Schwab account of billionaire movie producer Sidney Kimmel, turned the money into gold coins and used a portion to buy a $4.4 million mansion in Buckhead.

Weekes, who received a 17-year prison sentence for robbing the delivery drivers, is now in far deeper trouble. He faces the death penalty and is accused of ordering the murders of three people on the outside to protect a lucrative contraband ring. One victim, an 88-year-old man, was shot to death in his bed in what prosecutors say was a case of mistaken identity.

Brandt received a life sentence for his role in the Gwinnett crime spree. Although the crimes that sent him to prison 15 years ago weren’t gang-related, he’s now the top defendant in a massive federal gang indictment that says members of Sex Money Murder, a subset of the Bloods, engaged in murders, drug trafficking and fraud from inside Georgia prisons.

The circumstances in each case shed light on the realities of an incredibly expensive prison system that isn’t working, said Michele Deitch, an attorney and a distinguished senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin’s LBJ School of Public Affairs who directs the school’s Prison and Jail Innovation Lab.

“Georgia’s prison system is not accomplishing a goal of public safety because people are still committing crimes both while they’re incarcerated and after they get out,” Deitch said. “It is clearly not serving to rehabilitate people, if incarcerated people are still involved in these kinds of criminal behavior. There is no meaningful incapacitation if they still have the ability to be involved in criminal activities while they are locked up. And no one appears to be deterred from criminal behavior just because they are incarcerated. The public is getting nothing for its money, except a worse outcome.”

The cases also demonstrate how, even when the GDC has evidence of illegal activity, it’s often unable to shut it down. The AJC’s yearlong investigation of the Georgia state prison system has found hundreds of corrupt guards have smuggled in contraband, prisoners dying from drug overdoses at alarming rates, drug rings operating with abandon and understaffing to the point that it has led to record numbers of homicides.

By 2018, the GDC had learned, through a forensic analysis of a confiscated cellphone, that Cofield had amassed nearly $1.5 million from financial crimes, according to a copy of the analysis report obtained by the AJC. But Cofield wasn’t charged with a crime until 2020, when federal authorities uncovered the $11 million theft from Kimmel’s Charles Schwab account.

Similarly, a whistleblower lawsuit filed by an officer at Smith State Prison suggests the GDC had reason to look closer at contraband issues that could have pointed to Weekes, yet the department failed to do so. According to the lawsuit, GDC officials were told the warden, Brian Adams, wasn’t policing contraband months before he was fired and arrested on charges that he was involved in a multimillion-dollar contraband scheme directed by Weekes.

The officer who filed the suit, Julia Roberts, told the AJC that Adams was allowing packages that should have been blocked to come into the prison. But when she reported him, she said, investigators brushed off her tip. She said GDC officials then informed Adams, prompting the warden to berate her for going over his head.

“He just flat told me if I had an issue that I was to take it to him, that I was not to go over his head again,” said Roberts, who worked in the prison’s mailroom at the time.

The federal charges in Brandt’s case also raise the issue of what the GDC knew — or should have known. One of the matters detailed in the indictment, unsealed in November, dates to 2013, when, by the government’s account, Brandt and two other members of Sex Money Murder distributed heroin to a man then in federal prison in Pennsylvania.

Prosecutors say Brandt’s crimes continued for a decade, as he directed drug sales in the Atlanta area, told corrupt guards to smuggle drugs into prison, orchestrated financial crimes and gave the go-ahead for violent attacks on other inmates.

`So many different scams’

Jose Morales, a retired Georgia prison warden, said prisons have always been places where people can learn to become more polished criminals. He saw it firsthand as the warden at the Special Management Unit, Georgia’s so-called super max prison in Butts County, when Cofield was there. That a teenager with a seventh-grade education and a long prison sentence could become a criminal mastermind isn’t too farfetched, given the environment, he said.

“You get some of the shrewdest criminal minds in the prison system, and people learn from them,” Morales said. “There are so many different scams they’re running in there, it’s unbelievable.”

Morales said the GDC’s acute staffing shortages and its inability to stem the tide of contraband cellphones have enabled prisoners in their criminal pursuits. Beyond providing communication with the outside world, smartphones provide prisoners with access to social media, which, in turn, allows them to promote their exploits, he said.

“They become popular,” Morales said of the people with outside access through use of the phones. “It feeds their egos, and so the (criminal) lifestyle continues while they’re doing life in prison.”

“You get some of the shrewdest criminal minds in the prison system, and people learn from them."

For many who arrive in Georgia’s prisons, it’s hard to focus on preparing for release. Georgia’s sentences tend to be extraordinarily long, with parole often not even an option, especially for violent offenses. That’s especially true for Brandt, who was sentenced in 2007 to a stunning seven consecutive life sentences plus 265 years, then a record in Georgia, for the home invasion and two armed robberies.

“Without some hope or belief that they’re not marking their days until they die, they will find ways to spend their time and not always in ways beneficial to the public at large,” said Mark Yurachek, one of Brandt’s attorneys.

As time behind bars passed for Cofield, Weekes and Brandt, they came up with schemes that empowered them and endangered others, prosecutors say.

‘Young and Paid’

Less than three weeks after his 16th birthday, Arthur Lee Cofield Jr. walked into a branch of First Choice Community Bank in Douglasville, pulled out a Lorcin .380 handgun and demanded money from the tellers. He got $2,600 and made it to the parking lot before the episode went south.

As soon as he got into a cohort’s stolen Dodge station wagon, Cofield was covered with red dye. Not long after that, his cohort crashed the vehicle. Running, the two had to navigate a wooden fence. It took Cofield several tries to get over it.

Not surprisingly, police quickly put the pieces together and built the case that sent Cofield, aka “Little Co,” to prison. He was still 16. Nothing about him screamed “master criminal” — until he entered the Department of Corrections and became one.

Documents recently obtained by the AJC show Cofield was raking in cash through financial scams years before he was caught by the feds and that the GDC had compelling evidence of it.

“[Georgia's prison system] is clearly not serving to rehabilitate people, if incarcerated people are still involved in these kinds of criminal behavior."

In 2014, a confidential informant told law enforcement officers from Atlanta and surrounding communities that Cofield was leading a fraud ring that stole people’s identities, then purchased items at Home Depot, Best Buy, Apple stores and other retail outlets, using the victims’ store accounts. The stolen items were picked up at the stores and fenced, the informant said.

“The (informant) believes Cofield has made many thousands of dollars from this operation, and in fact has thousands of dollars inside the prison,” states a memo outlining the meeting with the informant.

Four years later, Cofield was engaged in more sophisticated and apparently lucrative scams, according to the GDC’s forensic analysis of a cellphone confiscated from him at the now-closed Georgia State Prison in Reidsville.

The analysis showed Cofield had accumulated $1.473 million in assets and cash transactions. At least seven other prisoners and three outsiders were identified as working with Cofield in what was described as a “large scale, multi-faced, multi-victim” fraud.

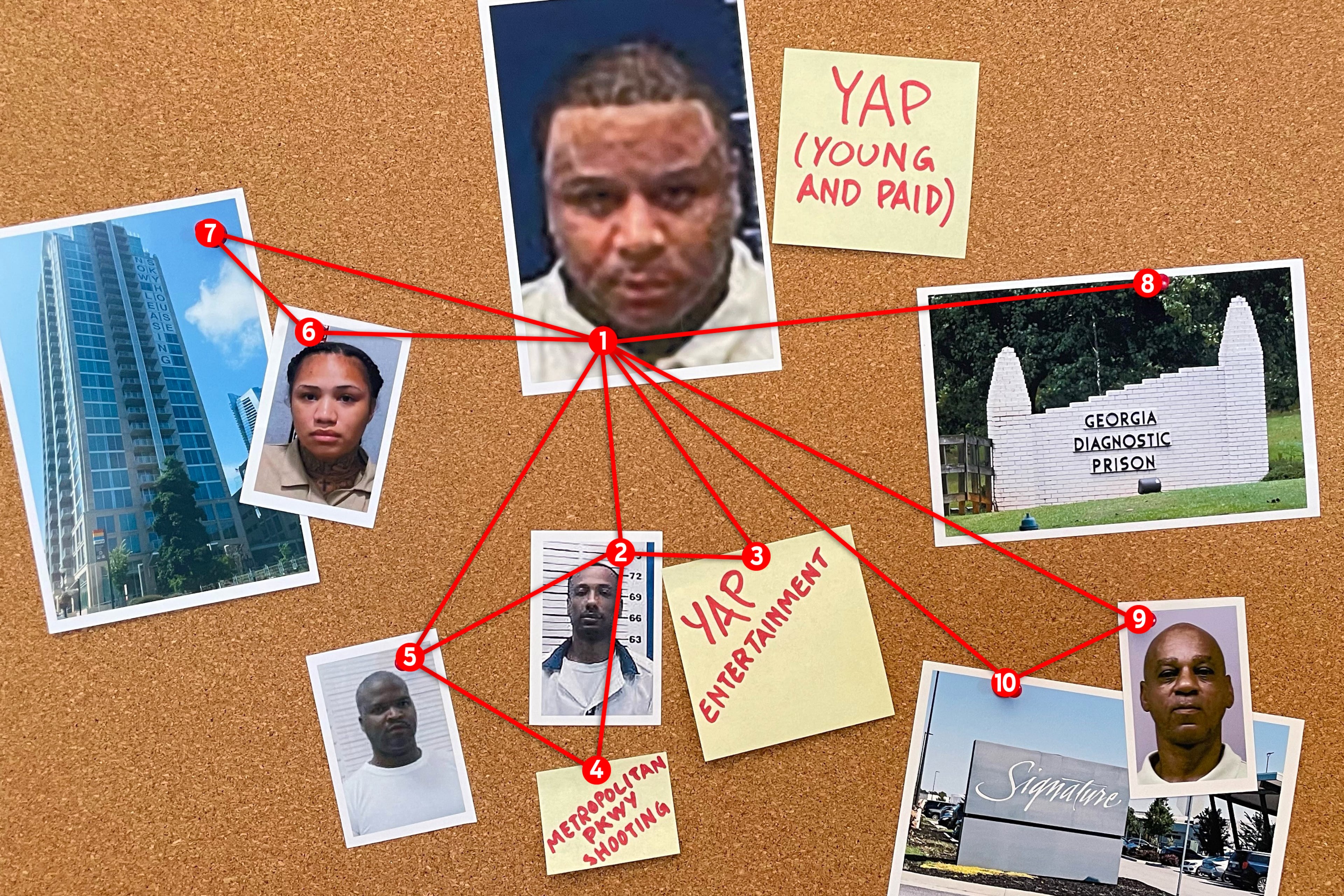

YAP (Young and Paid)

1. Arthur Lee Cofield Jr., aka Little Co, aka YAP Lavish: As a Georgia prisoner, he formed his own crew, short for Young and Paid, and stole millions from the accounts of unsuspecting citizens.

2. Devinchio Rogers: YAP crew member convicted for his involvement in the 2018 shooting of an Atlanta man, allegedly on Cofield’s orders.

3. YAP Entertainment: company formed by Cofield and incorporated with the Georgia Secretary of State while he was in prison.

4. 675 Metropolitan Parkway: the parking lot in Atlanta where the shooting occurred.

5. Teontre Crowley: YAP crew member convicted as the shooter.

6. Selena Holmes: Atlanta woman who had a phone relationship with Cofield and was convicted for a role in the shooting.

7. Skyhouse Buckhead: the high-rise apartment building where Holmes was living at Cofield’s expense.

8. Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Jackson, the location of the GDC’s Special Management Unit: Cofield was incarcerated there when he stole $11 million from the Charles Schwab account of billionaire movie producer Sidney Kimmel.

9. Eldridge Bennett: Lawrenceville man guilty of money laundering for serving as a courier in the $11 million heist.

10. Gold coins purchased by Cofield from an Idaho company arrived in Atlanta by private plane and were picked up by Bennett using a fake ID.

Photo credits on illustration: 1, 2, 5, 6 and 9: Georgia Department of Corrections; 7: J. Scott Trubey/AJC; 8: Hyosub Shin/Hyosub.Shin@ajc.com); 10: Natrice Miller/Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

The analysis found photos of mail and checks stolen from an Atlanta construction company executive, a bill of sale for a $449,080 Lamborghini Aventador and email exchanges regarding purchases of gold coins. It also found that Cofield, using an alias, had been in email contact with a private investigator, seeking to obtain rap artist Young Thug’s personal banking information.

By that time, Cofield was openly flaunting his wealth with a crew he’d put together in prison known as YAP, short for Young and Paid. Cofield, the leader, was called YAP Lavish. Photos of a gem-encrusted YAP necklace amid piles of cash were among those on the phone analyzed by the GDC in 2018.

The group became known for renting out clubs for parties and promoting itself on social media. At one point, it was even incorporated. Filings with the Georgia Secretary of State in 2017 and 2018 listed Cofield as a general partner in YAP Entertainment LLLP and gave his address as a house in Decatur.

The money and the status also brought women, and Fulton County prosecutors believe Cofield’s relationship with one — 25-year-old Selena Holmes — led to a shooting that left an Atlanta man paralyzed from the waist down.

Prosecutors believe Cofield ordered the shooting of the 37-year-old man, shot nine times in the parking lot outside a southwest Atlanta recording studio shortly after noon Sept. 21, 2018, because he believed the man was involved with Holmes. Although Holmes’ only contact with Cofield was by phone, she was known as YAP Missus and was living in the Skyhouse Apartments in Buckhead — rent, $2,887 a month — at Cofield’s expense.

“I’ve known Mr. Cofield for a long time,” Marissa Viverito, an investigator with the Fulton district attorney’s office, stated during a court hearing related to the shooting. “He finds these women from the outside and kind of pretends like he owns them from the inside using money and things like that, and they enjoy the lifestyle, so they go along with it, and they go along with it as long as the money is good, which is what Ms. Holmes was doing.”

Prosecutors contend that Cofield was on the phone with the shooter and another man, both of whom had been part of his YAP crew in prison, during the drive-by. Holmes was there, too, as a lookout. The two men and Holmes have pleaded guilty to their roles in the shooting and received lengthy prison sentences. Cofield has pleaded not guilty.

After the shooting, the GDC moved Cofield to the Special Management Unit, where he was confined to a single-man cell and allowed only limited interaction with other prisoners. Even there, he was able to steal the $11 million, turn it into gold and use a portion to buy a mansion before Morales seized the phone that allowed federal investigators to uncover the scheme.

The total of what Cofield made from his scams is not clear in court documents. But Morales says he saw a bank statement for $31 million on the screen of one of the many cellphones he confiscated from Cofield. He said he was able to view the screen only briefly before the phone automatically locked.

“Cofield was smart,” Morales said. “He let other people do his bidding. I mean, the guy knows how to play the role. He didn’t draw attention to himself. He was so quiet you wouldn’t even know he was there. But every other day, we found a phone on him. So he had people in his pocket.”

Cofield, now 32, has been in federal custody since his state sentence ended in October 2021. In April, he pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit bank fraud and aggravated identity theft. He’s due to be sentenced in January, and the government is recommending a prison sentence of 151 months.

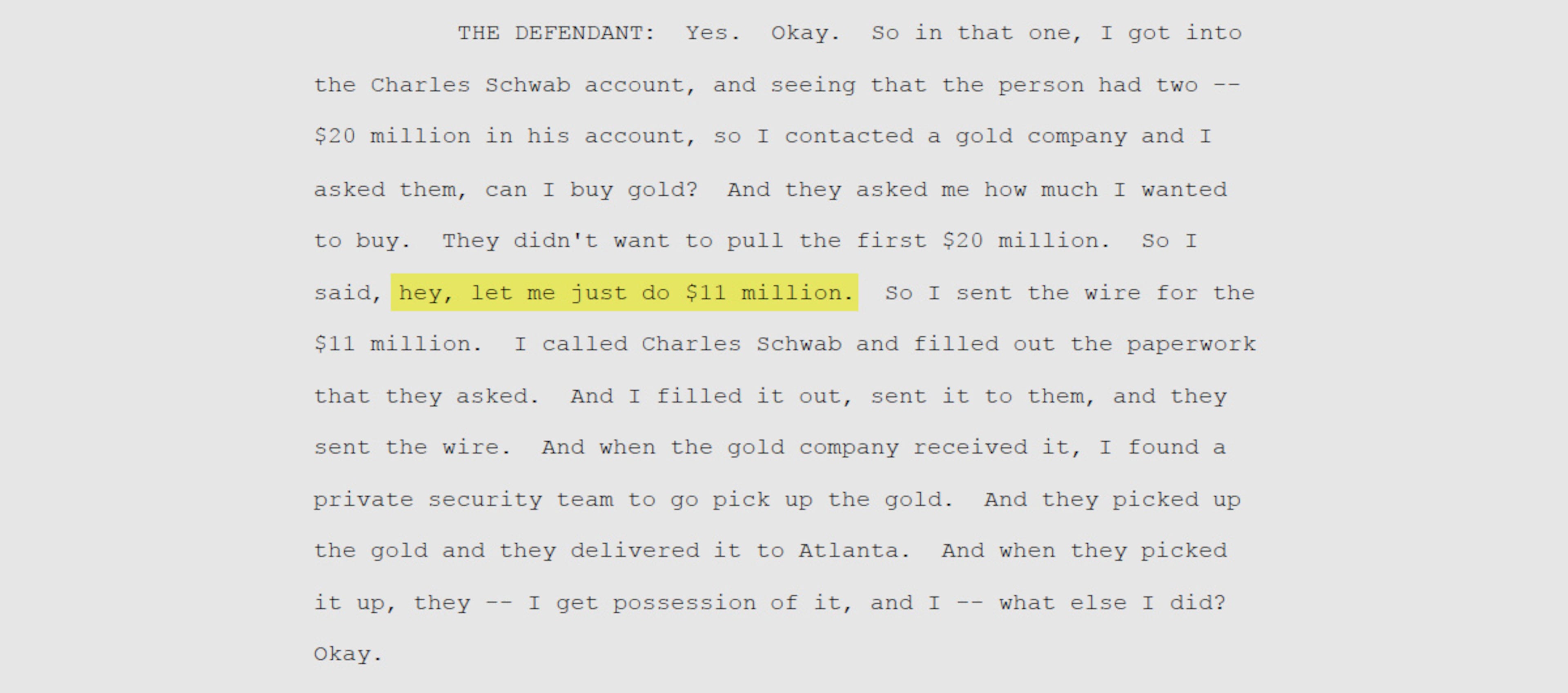

At the plea hearing, Cofield admitted to the $11 million Charles Schwab scam and another, in which he siphoned cash from a PNC Bank account and also turned it into gold.

The second scenario matches a 2018 theft of $650,000 from the PNC Bank account of a prominent Birmingham, Alabama, orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Kenneth Bramlett, that was subsequently investigated by local and federal authorities.

Recently interviewed for this story, Bramlett said he learned from authorities that a Georgia prison inmate was behind the heist, but Bramlett was never given that person’s name. Asked to describe what went through his mind when he heard that a prisoner was the mastermind, he responded with sarcasm.

“That’s very comforting,” he said. “Yeah, I mean, who knows what else is going on, right?”

A decade-long conspiracy?

Filling two boxes, the documents from Ryan Brandt’s court case in Gwinnett County describe in stark detail how he and another man robbed and terrorized a family in their home, then days later robbed two restaurants — a Fuddruckers and an Applebee’s. But nowhere in any of those documents does the word “gang” appear.

It took 15 years in Georgia prisons for that label to attach itself to Brandt, now 44. It’s a label that may say as much about life inside as it does about Brandt himself.

In the recently unsealed federal indictment, the government alleges that Brandt, along with 22 other members and associates of Sex Money Murder, took part in a decade-long conspiracy that includes a series of murders — both inside and outside prison walls — as well as drug trafficking and financial crimes.

Brandt is the first defendant listed in the 31-page indictment, which also identifies him by his street names: “Street Life” and “Robert Kraft.” The reference to the owner of the six-time Super Bowl champion New England Patriots is an apparent nod to Brandt’s stature within the SMM hierarchy.

If, as the feds allege, Brandt is indeed now a high-ranking member of Sex Money Murder, the extraordinary sentence has to be considered a factor, said Yurachek, who represented Brandt in his appeal.

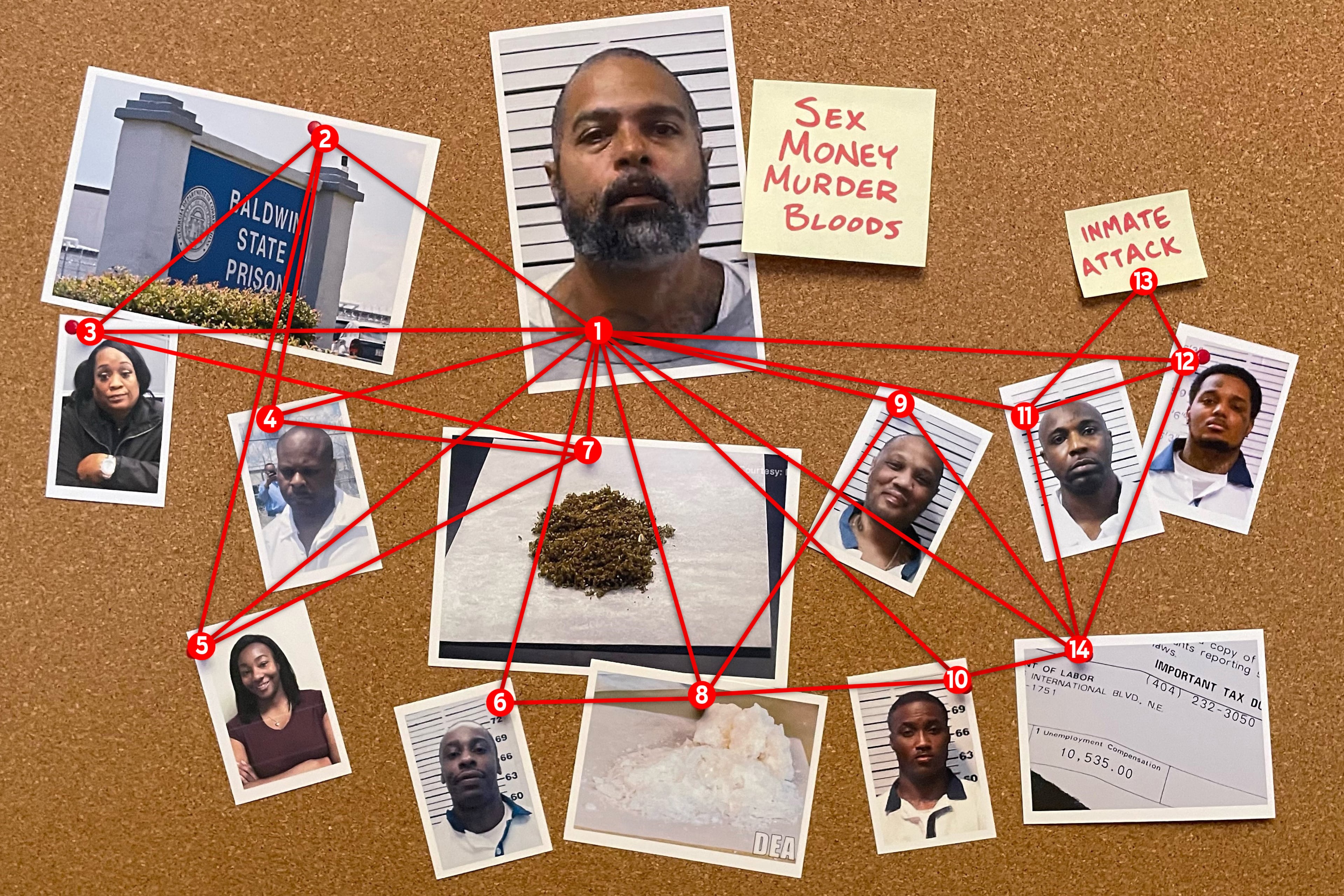

Sex Money Murder Bloods

1. Ryan Brandt, aka “Street Life,” aka “Robert Kraft:” Top defendant in federal indictment of Sex Money Murder subset of the Bloods alleging drug trafficking and financial crimes organized inside GDC facilities.

2. Baldwin State Prison, GDC facility in Milledgeville where Brandt is alleged to have trafficked in meth and “sheets” (paper laced with drugs).

3. Shounnette Wooten: Former Baldwin State Prison officer allegedly involved in Brandt’s drug trafficking.

4. Tracey Wise: Former lieutenant at Baldwin State Prison allegedly involved in Brandt’s drug trafficking.

5. Kierra Williams: Former officer at Baldwin State Prison allegedly involved in trafficking drugs with Brandt.

6. Elton Jackson: Inmate at Telfair State Prison linked to meth trafficking and a scam to fraudulently obtain $140,000 in unemployment benefits.

7. K2: Synthetic pot, also called “Spice,” typically sprayed on paper and smoked.

8. Meth.

9. Kyle Oree: Inmate at Washington State Prison linked to meth trafficking and the unemployment benefits scam.

10. Chase Pinckney, aka Chase Pickney: Inmate at Ware State Prison linked to meth trafficking and the unemployment benefits scam.

11. Anthony Jernigan: Inmate at Hays State Prison alleged to have ordered the murder of an inmate at Hancock State Prison and been part of the unemployment benefits scam.

12. Demarco Draughn: Inmate at Macon State prison alleged to have murdered the inmate at Hancock State Prison on Jernigan’s order and been part of the unemployment benefits scam.

13. Oct. 11, 2017, murder at Hancock State Prison that feds contend was the result of the victim’s violating the gang’s rule against homosexual activity.

14. Unemployment benefits form, similar to what could have been used by gang members to carry out the alleged scam.

Photo credits on illustration: 1, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12: Georgia Department of Corrections; 2: Hyosub Shin/hshin@ajc.com; 3, 5: Ga. Peace Officer Standards & Training; 4: POST case file; 7, 8: Drug Enforcement Administration; 14: AJC photo illustration

“For you to tell me he’s tied up with a gang, that stuns me, quite frankly,” Yurachek said. “But the line I draw pretty quickly is you have put this guy away forever (and) given him a sentence that might be called ‘death by incarceration.’”

The crime spree that sent Brandt to prison started when he and William Kollie, a co-worker, forced their way into the home of a Snellville couple and their 6-year-old daughter. When the man answered the door, Kollie shot him in the arm. Brandt and Kollie then bound the man, his wife and the 6-year-old with duct tape and stole a variety of items, including guns, jewelry and the family’s Toyota Sequoia.

Thirteen days later, they robbed the restaurants. They were caught after the Applebee’s robbery, when police stopped Kollie’s Ford F-150 Harley-Davidson for speeding at roughly the same time they received an alert to be on the lookout for the distinctive black truck.

After rejecting a plea that carried a 40-year prison sentence, the pair was convicted at trial. In handing down the seven consecutive life sentences, Judge Debra K. Turner said of the two men: “All I know is the behavior you’ve exhibited is inhumane, it is amoral, it shows no regard for life — not yours and not anyone else’s.”

“Without some hope or belief that they're not marking their days until they die, they will find ways to spend their time and not always in ways beneficial to the public at large."

Lisa Jones, who prosecuted the case, said she remembers Brandt and Kollie as warehouse workers in their 20s who simply saw an opportunity to enrich themselves at the expense of others. They weren’t motivated by drugs or gang ties, she said.

“I think they just wanted power,” she said. “They wanted to take what they wanted. It was just like, `What the hell?’”

Given the violence in the home invasion, she said, the sentence was appropriate.

But it didn’t achieve the goal of stopping further crime.

The federal indictment, in fact, paints the picture of a much more dangerous criminal. It puts Brandt in the middle of a broad and deadly conspiracy in which SMM members used contraband cellphones to orchestrate a variety of criminal activities from inside multiple GDC facilities.

One of the more chilling matters included in the indictment is the fatal shooting in 2014 of 9-month-old Kendarius Edwards Jr., a killing that occurred during a retaliatory hit at his mother’s home in DeKalb County. Although an SMM member has been convicted for ordering the shooting from inside Autry State Prison, the indictment suggests that others will also be prosecuted.

Brandt is directly cited multiple times in the allegations. The most serious of them contends he was dealing meth and “sheets” — paper soaked with drugs, most often a synthetic form of marijuana. In several instances, he allegedly had help from three officers at Baldwin State Prison: Tracey Wise, Shounnette Wooten and Kierra Williams. Wise, a lieutenant, admitted when he was fired in 2021 that he had smuggled in drug-laced papers for Brandt three times and received $2,500 each time.

The indictment also states that Brandt gave another SMM member permission to delay stabbing an inmate, another sign of Brandt’s key role in the gang.

Brandt’s sister Melanie Yancy said she doesn’t know the details of her brother’s life in prison. But she knows dealing with a lengthy prison sentence means figuring out a way to survive.

“You’ve got a corrupt system,” she said. “You’re in prison. It’s do-or-die. You’ve got the Muslims. You’ve got the white folks. You’ve got the Black folks. And you’ve got the guards. Which side do you want to be on? That’s the lay of the land. And with the amount of time you have, it’s live or die in there. If you want to stay alive, you’ve got to pick a side.”

`It seems unfathomable’

Nathan Weekes was 14 when, in 2010, DeKalb County police officers investigating a holdup found him hiding in the attic at a friend’s house four days after Christmas.

Weekes quickly confessed, describing how he and two older friends had held up a series of delivery drivers over several weeks that December, netting cash and food. He admitted he had been the one who pointed a broken gun at the drivers and that one of his friends had used a rock inside a sock to beat a man delivering Chinese food.

“He was bleeding real bad and I grabbed the food and ran off,” Weekes told police.

At the time of the holdups, Weekes had been in the U.S. for just four years, having immigrated with his family from the South American country of Guyana. Adjusting to a new life hadn’t been easy. He was doing well in school but had trouble fitting in and making friends. He started hanging out with the two older kids, one 16 and the other 18, who were part of the crime spree. Together, they committed 11 armed robberies over a few weeks.

After pleading guilty in 2012, Weekes was sentenced to 17 years in prison — more time than he’d been alive at that point. At the sentencing, his mother, Beverly Weekes, told the judge she didn’t raise her son to be a criminal. “He was never a child like this. He was always loving,” she said. She was hopeful about what might happen to her son someday, saying she left things in God’s hands. “I know he will place my son back into my arms,” she said. “I know.”

It hasn’t worked out that way. Raised, more or less, by the Department of Corrections, Weekes, now 27, is a man accused of deadly crimes that have left a South Georgia town unnerved.

Yves Saint Laurent Squad

1. Nathan Weekes, aka “Kash” and “Da President”: alleged head of the “Yves Saint Laurent Squad.” Investigators say he operated a massive prison contraband scheme and orchestrated three murders.

2. Christopher Reginald Sumlin, Jr: Former inmate at Smith State Prison. Alleged triggerman in murder of Bobby Kicklighter. Also accused of other crimes to protect the criminal enterprise.

3. Crash scene in Hinesville, where Sumlin is accused of car chase and shooting at a correctional officer in 2021.

4. Glennville home where Bobby Kicklighter, 88, was murdered in 2021. Prosecutors say Weekes’ ordered a hit on a correctional officer but Kicklighter was killed by mistake.

5. Aerial Deshay Murphy: pleaded guilty for her role in the Kicklighter murder.

6. Brian Adams: former warden at Smith State Prison, arrested in February for allegedly being part of Weekes’ enterprise.

7. Smith State Prison: high-security prison in Glennville where prosecutors say Weekes built a criminal enterprise with the help of corrupt prison employees.

8. Sharie Shonta Clark: former lieutenant at maximum security Special Management Unit in Jackson. Accused of moving $30,000 around for Weekes.

9. Cash App: mobile payment Clark is accused of using to move Weekes’ money

10. Keisha Janae Jones: Former Smith State Prison correctional officer. Prosecutors say she was Weekes’ girlfriend and acted as treasurer and facilitator on the outside for contraband ring. Co-defendant in Kicklighter murder.

11. Dennis Kraft: Accused in murder of Jessica Gerling. Prosecutors say he is a friend of Keisha Jones.

12. Jessica Gerling: former Smith State Prison correctional officer who went to work for Weekes’ enterprise, but was murdered in 2021 in a hit prosecutors say Weekes ordered.

13. Scene of Jessica Gerling murder in June 2021.

(Photo credits on illustration: 1, 2, 3, 7, 13: Lewis Levine; 5, 6, 8, 10, 11: Georgia Department of Corrections; 12: Courtesy of Photographic Memories)

It was a botched crime, the murder of 88-year-old Bobby Kicklighter, that allowed investigators to identify Weekes as a prison crime lord. According to investigators, Weekes sent a crew of associates to the Glennville home of a Smith State Prison officer who had been aggressively cracking down on contraband. But the crew went to the wrong house and shot Kicklighter, who was in bed at the time.

A critical piece of evidence discovered at the scene, a COVID-19 style mask with a name on it, eventually led investigators to the getaway driver, Aerial Deshay Murphy, and to the alleged triggerman, former prisoner Christopher Sumlin.

Phone records tied the crimes to Weekes and a former correctional officer, Keisha Janae Jones, described by investigators as Weekes’ girlfriend.

When investigators announced they had solved the case, the town was shocked to learn that someone inside the local prison was responsible for killing their neighbor.

“You could have given us 1,000 guesses over 1,000 years and nobody could have ever thought of something like this,” said Dylan Mulligan, a Glennville attorney and friend of the Kicklighter family who has served as their spokesman. “It seems unfathomable that something like that could have actually happened.”

Kicklighter’s killing was one of three that prosecutors believe were part of a plan by Weekes to protect the “Yves Saint Laurent” squad, the thriving contraband enterprise he was operating inside Smith State Prison. Weekes is also charged with ordering the murders of Jerry Lee Davis, who had a job delivering supplies to the prison, and Jessica Gerling, a former correctional officer who has been tied to the contraband scheme.

Weekes, who went by “Kash” or “Da President,” had figured out how to pay off or threaten guards as well as recruit other prisoners and people on the outside to help him smuggle in drugs, jewelry, weapons and cellphones, all of which he sold at a profit. Adams, the warden, was also in on the scheme, according to the charges that cost him his job.

In videos filmed inside Smith State Prison and posted on social media, Weekes bragged about the squad’s ability to continue criminal activity behind bars.

Weekes was eventually moved to the Special Management Unit, but, like Cofield, he wasn’t deterred by the added security.

Not long after Weekes arrived at his new facility, multiple criminal charges were filed against a veteran correctional officer there, Lt. Sharie Clark. The basis for the charges: She had accepted $2,000 in Cash App payments from Weekes in exchange for moving $30,000 to multiple subjects.

When Weekes was sent to prison, the superior court judge who sentenced him, Cynthia Becker, said she understood how the length of a 17-year sentence would sound to teenagers. She said she had a teenage son herself.

“Justice requires justice, not only for defendants but for victims in the community,” she said, speaking to Weekes and one of the other teens. “And while I’m not comfortable with the sentence — I’m never comfortable sending young men off — I do believe it is just. Now, the two of you, I’m going to impose sentence on you and it’s harsh. But you will still have love, support and a lifetime to make amends. OK?”

“Yes, ma’am,” Weekes replied.

The GDC responds

Joan Heath, the spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Corrections, said in a statement emailed to the AJC that the agency is committed to making sure any type of criminal activity is investigated and turned over for prosecution. She also noted that Cofield, Weekes and Brandt are just three people out of the nearly 49,000 in the state’s prison system, and she said their stories don’t represent the overall population.

The AJC requested an interview with Gov. Brian Kemp to discuss problems in the state prison system. The governor’s office declined the request.

About This Investigation

This is the latest installment of an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation into the extensive problems in the Georgia prison system. To see whether the prison system is fulfilling its mission, AJC reporters explored the stories of three men serving long sentences who have gained notoriety behind bars. All three are accused of committing crimes while incarcerated that are more serious than those that sent them to prison.

The AJC also examined whether the prison system is impeding the public’s understanding of what’s happening in Georgia prisons through a lack of transparency.

The stories in this installment are based on court records, trial and hearing transcripts, police and other law enforcement reports, Georgia Department of Corrections records and responses to requests for information as well as interviews with experts, officials and those involved with the cases the AJC studied.

The first installment of this investigation, published in September, revealed extensive corruption by Georgia prison employees and its role in triggering violence. In October, the AJC’s second installment revealed how fatal drug overdoses have dramatically increased in Georgia prisons. In November, the third installment revealed grim new records for homicides and suicides amid drastic understaffing at many of the state’s most violent prisons.