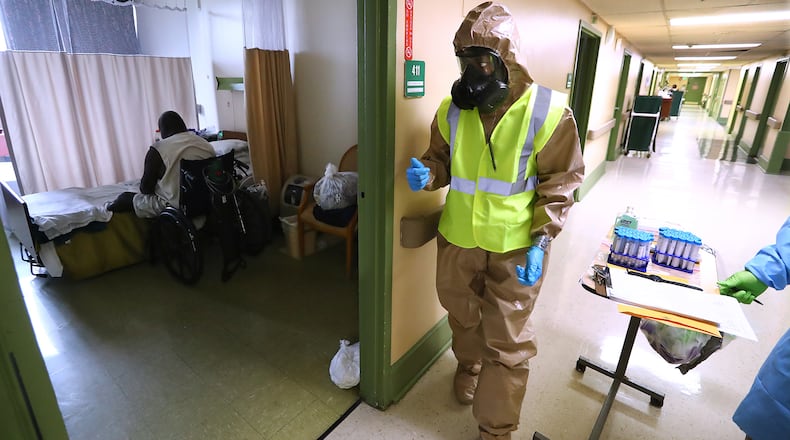

A chilling scene emerged in mid-April at Legacy Transitional Care and Rehab in Atlanta.

Eight residents and three staff members had already tested positive for COVID-19. More tests were pending. Yet, the management of the massive nursing home with 160 residents didn’t appear to be on high alert.

On that Saturday afternoon, according to state records, the home had only eight staff members working. A state public health official was told no one at Legacy could speak about conditions inside the home: The facility’s top nurse and the home’s administrator weren’t there, and the weekend supervisor had left.

That set off a multi-agency emergency response.

By the next day, 20 residents had been hospitalized. A medical team and the Georgia National Guard had been sent in. The responders worried about understaffing, but the home’s administrator “expressed that he did not see the need to request additional staffing at this time,” according to emails obtained by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution through the Georgia Open Records Act.

At Legacy, a for-profit facility where up to four residents live in each room, understaffing is routine, according to a review of workforce data submitted by the nursing home.

Legacy was among the lowest-staffed nursing homes in the state between April and June, according to the records. But it was hardly the only Georgia home with staffing levels experts say aren’t adequate to care for a vulnerable population, especially in the midst of a pandemic, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation has found.

Georgia ranked 43rd nationally for average hands-on care staffing at its nursing homes during the second quarter of 2020, according to a new report by the Long Term Care Community Coalition. The state ranked even lower — 48th — for hands-on RN staffing, according to the report.

At Legacy Transitional Care and Rehab, the number of residents testing positive for COVID-19 went from 15 to more than 100 in a single day in April. Twelve of the home’s residents and two staff died with COVID-19, according to the facility’s reports to government agencies. Statewide, nursing homes, assisted living communities and large personal care homes have reported the deaths of more than 2,800 residents from the disease, about a third of Georgia’s total known COVID-19 deaths.

Legacy’s executive director did not respond to the AJC’s requests for an interview.

Research conducted in California found that nursing homes that weren’t staffed at recommended levels with nurses were more likely to have COVID-19 outbreaks, said Charlene Harrington, professor emeritus at the University of California San Francisco and one of the nation’s top experts on long-term care.

Having a stable, well-trained staff, along with enough testing and PPE, are the critical factors for nursing homes, she said. “Without those things, the poor residents are just sitting ducks for this virus,” she said.

Pandemic drains staffing

Well before the pandemic, Georgia’s nursing homes struggled to find enough nurses and certified nurse aides to fill their 24-hour schedules, amid a shortage nationwide.

When the COVID-19 outbreaks started hitting nursing homes, the staffing issues got much worse. More than 9,000 long-term care workers in Georgia have tested positive for COVD-19 at some point during the pandemic, forcing them into quarantine. Employees who don’t test positive sometimes stop showing up when an outbreak does hit, out of fear that they won’t stay safe.

But nursing homes need even more nurses now than they did before, said Neil L. Pruitt, Jr., chairman and CEO of Atlanta-based PruittHealth, one of the largest senior care companies in the Southeast.

Facilities are often handling residents with multiple chronic conditions on top of the threat of infectious disease. He said his company is working to hire additional registered nurses to focus just on infection prevention, and so far the company has filled 47 of 91 positions. Pruitt said his company has increased compensation and implemented retention bonuses to keep nurses.

But he said it’s tough to find new staff and hold onto current employees because they’re being heavily recruited by staffing agencies and other providers. Plus, he said, some older nurses with health issues, who face risks if they contract COVID-19, are leaving the profession. “There is a supply problem, and whoever will pay the most right now is winning,” Pruitt said.

Aides typically are paid just $10 to $15 an hour, and Georgia nurses make less than many of their counterparts elsewhere in the nation. Those in the nursing home industry say that’s because the majority of their residents are covered by Medicaid, and Georgia’s reimbursement rates are relatively low.

“Everyone, regardless of constituency type — from academics, to advocates for the patients, to the head of the Certified Nursing Assistants, to me —strongly believe we need increased staffing in nursing homes,” Pruitt said.

He served on the national Coronavirus Commission on Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes, which recently issued a slate of recommendations, including one that calls for leveraging federal relief funds and using local health system resources to provide 24-hour RN staffing in nursing homes that are dealing with an outbreak.

A federal study in 2001 found that nursing homes need to provide an average of 45 minutes of RN staffing per resident each day, and about 4.1 hours of total care staffing to meet residents’ needs. But most homes nationally don’t reach that goal, and Georgia’s homes are even farther behind.

“There is a supply problem, and whoever will pay the most right now is winning."

In Georgia, the average nursing home provided just over half that RN time during the second quarter of 2020, according to the new data. For total care staff, Georgia nursing homes do better, but the vast majority don’t meet the targets that advocates and researchers say are necessary to complete tasks, the AJC found. Legacy Transitional Care reported just half the staff hours that those studies suggest.

Federal rules don’t require a specific staffing ratio for nursing homes, saying only that staffing must be “sufficient.” Georgia’s regulations stipulate that each resident must receive just two hours of direct nursing care a day.

“Georgia is really very, very close to the bottom,” said Richard J. Mollot, executive director of the Long-Term Care Community Coalition. He said the average hours Georgia nursing homes reported for total care staffing aren’t adequate and he called Georgia’s typical RN staffing “alarming.”

“How could you be providing care or supervision to a vulnerable population with that little amount of time?” Mollot said. “What are the impacts — not only on care for the residents but for the care staff who are under-supported?”

Weekends without nurses

Nursing homes across the country are required to have an RN on duty at least 8 hours every day, but the AJC’s review of staffing records found homes that reported days without any RN staffing at all, often on weekends.

Life Care Center of Gwinnett in Lawrenceville reported multiple days, often weekends, with no RN staffing in its reports for the second quarter of 2020.

The nursing home reported that 62 residents tested positive for COVID-19 during the pandemic and 19 died.

Ronald Gooden, the home’s executive director, said 24 staff members tested positive during the second quarter of 2020, placing a strain on staffing. Nurses from other Life Care facilities in the Southeast came to help out, he said, but their hours weren’t always reflected in the official report since they were employees of other homes.

He said four more staff members have tested positive since that outbreak — one in August and three in October. But he said infection-control measures protected residents. “We are currently COVID-19 free and are striving to keep it that way,” he said.

Harrington, the long-term care expert, called it shocking that homes would operate without RNs on weekends or holidays. She said homes get away with violating the rules because of lax oversight. But she said someone with an RN’s level of training is needed to assess residents who fall, or have heart attacks or strokes or other health issues so that the proper steps are taken.

“We want nursing homes to have RNs on duty 24 hours a day,” she said.

Having higher staffing levels and a stable staff helps residents, Harrington said. But many nursing homes across the country are plagued by both constant turnover and inadequate staffing. As a result, she said, aides are sometimes assigned twice as many residents to care for as they should be.

Any facility that is overloading its frontline workers, she said, isn’t allowing time for infection-control protocols.

“They’re racing from patient to patient to try to try to get the work done, and they can’t get it done. . . . They’re not doing handwashing because they don’t have time,” Harrington said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured