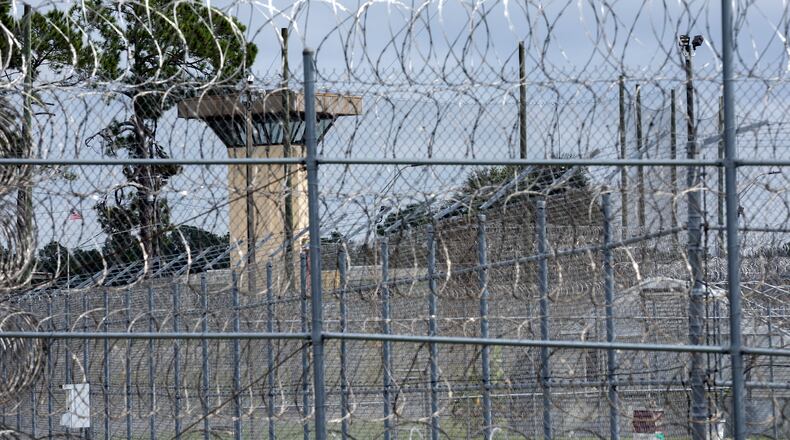

With prison violence in Georgia at a crisis point, the state Senate has authorized a group of senators to take a fresh look at the Georgia Department of Corrections and identify ways to improve the troubled system.

A new seven-member committee, approved unanimously by the Senate, is charged with examining “current issues impacting the ability of the Department of Corrections to operate secure and safe facilities and to ensure the welfare of both its staff and those in its custody.” The committee is to operate until December 1 and is expected to present findings and recommendations for the General Assembly to consider during its 2025 legislative session.

“What I want to do is take the prison system down to the foundation and look at every component within the Georgia Department of Corrections and basically inspect it, and look at it, and see if we’re doing it in the best way possible,” said Sen. Randy Robertson, R-Cataula, the sponsor of the resolution that created the committee.

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

The measure comes after The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, in a series of stories last year, exposed extensive corruption among prison employees, widespread drug use and drug dealing inside prisons, massive officer vacancies, record homicides and large criminal enterprises that operate inside state prisons — and victimize people on the outside — with the help of contraband cellphones. The prison system is also under scrutiny from the U.S. Department of Justice’s civil rights division, which since September 2021 has been investigating prison violence.

Now, new reporting by the AJC, using GDC mortality reports and death records, has determined that 2023 set a record for homicides inside Georgia’s prisons with 37 deaths, including the killing of a correctional officer at Smith State Prison. That number far outpaces prison homicides in recent years, the AJC found. In 2017, there were eight homicides in Georgia prisons, and in 2018 there were nine, according to the Georgia Department of Corrections. The homicide numbers have been climbing ever since, reaching 31 deaths in 2022.

While Gov. Brian Kemp has said little about issues within the prison system, legislators this year have insisted on improvements in security by putting more money in the budget to combat the widespread use of contraband cellphones and also upping criminal penalties for correctional officers who are caught smuggling contraband.

The new committee, which the resolution officially named the “Senate Supporting Safety and Welfare of All Individuals in Department of Corrections Facilities Study Committee,” won strong bipartisan support.

A spokeswoman for the GDC said it will be cooperating fully with the study. “We are committed to transparency in assisting both the members of the committee and the public in fully understanding the complexity of the corrections profession,” said the spokeswoman, Lori Benoit, in a statement emailed to the AJC.

Sen. Josh McLaurin, D-Atlanta, told the AJC he was grateful that the Senate took action and that the name of the committee reflects that safer prisons also protect the general public.

“Violence and gang activity inside the walls spill over into our communities unless we do something about it,” McLaurin said. “The solution starts with recognizing the humanity of the people inside and paying attention when they are in crisis.”

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

Credit: Arvin Temkar/AJC

The AJC has identified a series of deaths in communities tied to criminal enterprises operating inside state prisons. The most high-profile was the 2021 killing of 88-year-old Bobby Kicklighter, a beloved resident of Glennville, who was shot to death in his bed in the middle of the night. An investigation later determined that his death was a case of mistaken identity after a Smith State Prison inmate, Nathan Weekes, allegedly ordered a hit on a correctional officer who had lived next door to Kicklighter. Two other murders outside the prison have also been tied to Weekes.

Other hits ordered by Georgia prisoners include the 2021 murder and dismemberment of a 37-year-old mother of two, who was kidnapped from Plaza Fiesta Shopping Mall in DeKalb County because an inmate running a drug ring no longer trusted her. In 2014, the fatal shooting of a 9-month-old baby resulted from a hit ordered by an Autry State Prison inmate against the toddler’s mother. She was hit eight times as she held her infant son.

Improving abysmal staffing at Georgia’s prisons is one of the biggest challenges facing the system. As of January, more than half of correctional officer positions were unfilled at the majority of Georgia’s state prisons, the AJC found. At Smith State Prison, one of the most violent, two-thirds of correctional officer jobs were unfilled, leaving just 53 officers working at a prison that is supposed to have 160 officers, according to state staffing reports obtained through the Georgia Open Records Act. At nine state prisons, more than 70% of correctional officer positions were unfilled, creating a lack of supervision and safety for both employees and prisoners.

Robertson said it was important to study the staffing issue and come up with solutions to attract qualified officers. It’s important to maintain high standards in hiring, he sid. But to attract strong candidates, he said, the system needs to find ways to elevate the profile of correctional officers who play a key role in public safety but don’t always get the admiration that others in law enforcement do.

Robertson said it’s also critical to handle those sentenced to prison differently, depending on each person’s desires and abilities, so that public safety is improved. Some who want to continue to commit crimes need to be put in the most secure facilities possible, he said. But others need to be prepared to return to the community.

“I have played a role in putting a lot of good people in prison because they made a bad choice, not because they were terrible people,” said Robertson, who had a 30-year career in law enforcement and retired from the Muscogee County Sheriff’s office in 2015. “These individuals are going in there, and we’re responsible for what comes out on the other side. They can come out the same person they were, a better person or a worse person. A lot of that responsibility rests on the custodian, which is the state of Georgia.”

Robertson said the study committee needs to examine a myriad of other issues, including health care, security issues, rehabilitative programming and modernization of facilities.

“Nothing is off the table,” he said. “I want us to reimagine the Georgia Department of Corrections.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured