The state trooper pressed the gas as he sped through the darkness along I-75 in Cobb County. He later said he was trying to catch two vehicles weaving through traffic at 125 mph.

Over 6 miles, his focus narrowed to only one of the vehicles, a gray BMW coupe. He switched on his blue lights and approached to initiate a standard traffic stop for speeding, according to state records detailing the incident. Instead of slowing down, the driver of the BMW sped up.

The trooper’s Dodge Charger bore the logo of Georgia State Patrol. He sped up, too.

He radioed a dispatcher, and a call went out to other units: A chase was in progress.

As the two cars whipped down the interstate, hurtling toward the Downtown Connector, the fleeing driver tried to widen the gap between himself and the trooper. He jostled between lanes and drove on the shoulder in a construction zone, GSP records show.

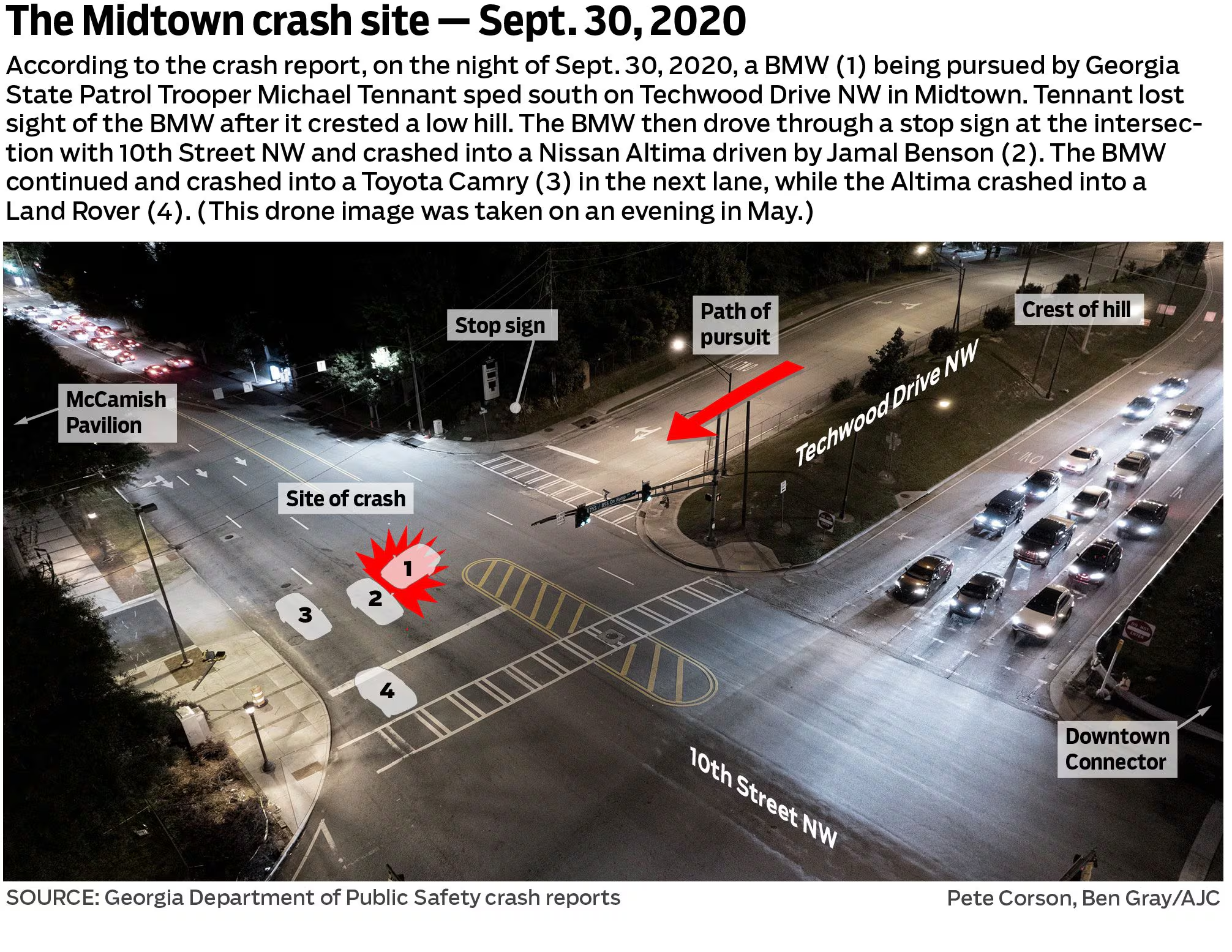

The BMW veered to exit onto a surface road in Midtown and sped past a red light. The trooper watched as the BMW disappeared over a hill.

First in a series

Future stories in this ongoing investigative series will explore various aspects of Georgia State Patrol pursuits and search for solutions that can help inform policymakers and the public.

Part 2: Georgia state patrol tactic meant to end chases leads to death at high speeds

Part 3: Bystanders injured in GSP pursuits have few legal protections

Fredricia Cain and her family — her teenage sister, her boyfriend at the time, his adult niece and the niece’s 3-month-old son — were all in a Nissan Altima that had stopped at a red light down the hill and in the BMW’s path.

“Next thing you know, bam!” Cain told the AJC, recalling that night in September 2020.

The BMW struck their car with such force that Cain’s boyfriend and his niece were ejected.

After the crash, Cain saw her teenage sister and the 3-month-old motionless in the back seat. The teen had already died, and the baby would later die after being hospitalized. Both were casualties of the GSP pursuit policy in action, one that often poses more danger to the public than the people being chased, an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has found.

The GSP policy defines a pursuit as “an active attempt” by a trooper in a patrol vehicle to apprehend a fleeing suspect who is attempting to avoid capture. GSP records describe the motorist as the one who initiated the pursuit by not stopping.

The AJC’s investigation found that Georgia has the worst death rate in the country from police pursuits. The state patrol’s aggressive tactics and loose chase policy contribute significantly to this grim ranking.

An AJC analysis of state data detailing GSP pursuits from 2019 through 2023 found troopers with the agency were involved in more than 6,700 pursuits in those five years, a figure that alarmed experts who reviewed the AJC’s findings. Many pursuits began with a traffic infraction, then reached high speeds and led to a crash.

More than 3,400 crashes involving GSP pursuits have left at least 1,900 people injured and 63 killed during that five-year period.

Those killed include a 12-year-old boy in Paulding County, after a trooper intentionally rammed the rear side of the car in which he was a passenger, leading the car to flip; a pedestrian in Savannah, a 56-year-old who was cleaved in half by a car as a pursuit sped through the walkable coastal city; and a 60-year-old man who died when his Toyota Camry was T-boned on the driver’s side by an out-of-control car during a GSP chase in DeKalb County that started over a suspected seat-belt violation.

Like Cain’s family, they were bystanders or passengers with no choice in the pursuits that left them injured or dead. The AJC’s investigation found bystanders and passengers are the people most often harmed during pursuits by GSP — their involvement akin to being caught in the line of fire during a police shooting.

And while troopers may not use their firearms every day, the data shows that the manner and frequency with which they use their vehicles can prove just as deadly. In 2023, a record year, GSP pursuits became an almost daily occurrence. There were only 14 days last year without a pursuit.

GSP high-speed pursuits have become so common, the agency has developed a reputation on social media. “GSP don’t play” has become a popular saying among online observers familiar with the agency’s aggressive tactics.

The AJC spent more than a year gathering and analyzing data on thousands of GSP pursuits to measure their risk and impact for those using Georgia’s roadways. Reporters interviewed law enforcement officials and experts, those directly injured in the GSP’s pursuits and family members who have lost loved ones in deadly pursuits. Georgia State Patrol Col. Billy Hitchens received a detailed accounting of the AJC’s findings and questions. Hitchens, who serves as Gov. Brian Kemp’s approved commissioner of the Department of Public Safety, which includes the GSP, declined multiple interview requests. The AJC sent Kemp the findings of its investigation and he declined an interview request.

In a written response from the agency, state patrol spokesman Capt. Michael Burns said the agency’s pursuit policy is “proportionally responsive” to the rise of crime on the roadways, including street racing, aggressive driving and speeding. GSP’s policy is based on “state and federal law, judicial rulings, dedicated training, and sound principles of law enforcement,” he said. (Read the full response here.)

“Every life is precious, and any life lost during the course of ensuring public safety is tragic and heartbreaking,” he said. “The Department of Public Safety protects Georgians by ensuring our members use good judgment and act within the bounds of policy and law.”

No national agency comprehensively tracks police chases, and varying state laws make direct comparisons challenging. But an AJC analysis of pursuit policies nationwide as well as an analysis of federal data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration suggests reason for concern.

The AJC’s investigation analyzed national data from 2018 to 2022, the latest year of federal data available, and found that people died in Georgia more often as a result of police pursuits than in any other state.

The federal data recorded 201 pursuit fatalities for law enforcement agencies in Georgia over those five years. GSP reported 68 pursuit fatalities involving the agency during that period, according to GSP’s annual pursuit reports. While the federal data from the NHTSA and the data obtained from GSP came from separate sources, the AJC’s analysis of each reached a similar conclusion: No other agency in Georgia is associated with as many fatal pursuits.

Reporters also reviewed 44 pursuit policies from state police agencies across the country for comparison. GSP’s policy is among the most permissive of the states reviewed by the AJC.

Unlike most other state law enforcement agencies across the country, the GSP policy offers troopers almost complete discretion and enables them to justify chasing just about anyone who runs — anywhere and for any reason, no matter the consequences.

Two people Cain loved died because of a crash linked to the pursuit that September night in 2020. No one was arrested that night, because the BMW driver escaped on foot moments before the trooper arrived to the crash scene.

GSP later concluded Trooper Michael Tennant might have violated policy, but only because he exceeded the speed limit without activating his emergency lights as he initially tried to catch up to the BMW, not because he chose to pursue over what would have been a traffic violation, including excessive speeding.

Tennant was authorized to decide, as troopers with GSP do nearly every day, whether the chase was worth the risk to the public.

It’s unclear what authority, if any, supervisors have in pursuits, because the GSP’s policy does not outline their role. The pursuit policy does not require supervisors to take command during pursuits to determine whether a chase should continue, as most states require.

While troopers can decide to discontinue a pursuit, they seldom do, the AJC found. And the policy doesn’t require troopers to receive authorization to perform risky, potentially life-endangering maneuvers to try to end a pursuit.

One such maneuver is called a precision immobilization technique maneuver, which involves the trooper ramming the rear side of a fleeing car in an effort to spin the car and bring it to a stop. Many agency policies nationwide restrict using PITs, especially at high speeds, but the GSP has no such restriction. The AJC identified cases in which troopers performed PITs while exceeding 100 mph.

Technological advancements in policing have made tracking and finding suspects easier and swifter than ever. But high-speed chases to catch fleeing motorists remains the norm at the GSP — one of Georgia’s largest law enforcement agencies.

These chases, which can endanger anyone on Georgia’s roadways, often stem from misdemeanors or traffic infractions, including broken taillights, driving without a seat belt, speeding or improper registration, the AJC found.

As police steadily adopt new technology, many also have heeded the recommendations that policy experts, researchers and some police executives nationwide have talked about for more than a decade: Initiate fewer pursuits to protect more members of the public.

The AJC’s conclusions about Georgia’s status as such an extreme exception are bolstered by data compiled by The San Francisco Chronicle for its recent investigation of police pursuits across the nation. In its investigation that concluded many fatal crashes are not reported to federal authorities as required, The Chronicle created the most comprehensive national accounting of fatal crashes in the U.S. resulting from pursuits. The Chronicle’s data confirmed that Georgia stands out, ranking first in terms of deadly pursuits relative to population.

“The cost of all the injuries and deaths is not worth it,” Lou Dekmar, a retired Georgia police chief and the former president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, told the AJC. “Especially when most of these started with misdemeanor offenses or traffic infractions.”

He ‘used due regard’ and ‘drove safely’

The Georgia State Patrol became nationally known in the 1970s, when its troopers played a part in the blockbuster movie “Smokey and the Bandit.”

The film showed the GSP blue patrol vehicles, with orange lettering, pursuing Burt Reynolds’ character as he sped off in his black Pontiac Firebird Trans Am. The movie celebrated the rollicking idea of high-speed pursuits and the cat-and-mouse game between police and those fleeing them. It helped cement an enduring image of GSP.

The state patrol is still known today for its troopers’ wide-brimmed hats and unrelenting pursuits. It has 837 sworn troopers to enforce traffic laws in Georgia’s 159 counties. The agency’s motto is “Wisdom, Justice and Moderation,” and its website says troopers must operate with trust and professionalism.

But troopers often fall short of these standards and ideals when it comes to pursuits that could harm the public, the AJC found. The review found that GSP leaders rarely find official fault with troopers’ actions during pursuits that result in deaths, according to an AJC analysis of the GSP’s internal affairs and post-pursuit reviews. And when problems are noted, the consequence is usually a verbal counseling or other low-level disciplinary action.

That was the case with Trooper Tennant — the officer who chased the BMW that slammed into Cain and her family in September 2020.

“He should have activated his patrol vehicle’s emergency equipment while initially trying to catch up to the BMW,” GSP Lt. Brandon Dawson, a supervisor, wrote in his report, prepared after he reviewed the fatal pursuit.

Georgia law requires a police officer to use their blue lights and siren when they exceed the speed limit during a traffic stop. During the initial chase, as Tennant was trying to catch up, he drove for several miles without his blue lights or siren, exceeding the speed limit, records show. That violated state law and GSP policy.

The internal review lasted one week. Aside from faulting Tennant for not turning on his emergency lights and siren, Lt. Dawson concluded that the rest of Tennant’s actions during the chase were within policy. The violation didn’t seem to impact the lieutenant’s assessment of the trooper’s performance.

“TFC Tennant operated his patrol vehicle safely, without using his emergency equipment, during his attempt to close the distance,” the lieutenant wrote, also noting earlier in the report that “TFC Tennant used due regard and drove his patrol vehicle safely throughout the pursuit.”

Tennant was a rising star in the GSP at the time of incident.

The year before, he had been honored with the GSP’s prestigious lifesaving award after he rescued a motorist who crashed into a wall on I-75 in Cobb County.

In 2021, he joined the state’s multiagency crime suppression unit — an initiative launched as part of Gov. Brian Kemp’s effort to crack down on violent crime and street racing in Atlanta.

In the approximately three years after the Midtown crash, Tennant was involved in 58 pursuits. His pursuits during that period have resulted in 28 additional crashes and 16 injuries, according to the AJC’s analysis of GSP data through 2023. Those figures placed Tennant in the top 10 among troopers in Georgia for pursuits and pursuit crashes during that period, the AJC found. The top 10 is dominated by troopers who operate in the metro area.

“TFC Tennant has been involved in numerous pursuits,” according to a supervisor’s assessment from a June 2021 pursuit critique report that reviewed an 11-mile chase from downtown that ended with a PIT maneuver on Cumberland Boulevard in Cobb County.

Flash of lights, then darkness

Cain and her boyfriend, Jamal Benson, had fallen on hard times during the pandemic. They’d both lost their jobs for a while when the world shut down, and the couple had struggled for several months.

A bright spot was the Nissan Altima that Cain had managed to purchase in August 2020, which gave her and her family a reliable way to get to work. Within days of buying the vehicle, a beaming Cain posted a photo of herself with the Nissan on Facebook.

“My new baby,” she wrote, adding, “feeling blessed.”

Benson was behind the wheel on Sept. 30, 2020, and Cain was in the front passenger’s seat when the group visited a nearby fast-food restaurant for a bite, according to Cain.

The burger joint had botched their order and delayed them by several minutes that night. They left hungry and without the food they had ordered. It was shortly after 9:30 p.m. as they sat, waiting for the traffic light to turn green at Techwood Drive and 10th Street. The family sat and waited quietly. The youngest among them, the 3-month-old boy, Kayden, was buckled in his car seat in the back between his mother, Emeral Benson, and Cain’s sister, Anjanae McClain, according to Cain.

The silence was shattered by broken glass and twisting metal. Jamal Benson said he remembers the flash of headlights so bright it made the world around him disappear into a white void before everything faded into blackness.

The force of the fleeing BMW striking the Nissan sent the Altima spinning, according to the crash report. Each car collided with other vehicles stopped at the light.

“It was all a blur,” Cain said. “I blacked out.”

When Cain woke up, McClain, whose seat was nearest to the impact, was unresponsive, with her seat belt still buckled. Cain told the AJC she touched her sister’s face, trying to encourage her to wake up. But McClain was already gone. First responders told Cain she died on impact.

“She was only, like, maybe 100-something pounds,” Cain said.

Benson’s niece, Emeral Benson, was badly hurt after being thrown from the back seat of the car, according to Cain. She was taken to Atlanta Medical Center while her 3-month-old baby was taken to Egleston Children’s Hospital, according to GSP records. Emeral Benson was in the hospital when Kayden was pronounced dead.

Jamal Benson, who was driving, was propelled from the vehicle through the windshield and thrown into the street. He remembers waking up twice.

The first time, he lay outside the car, his femur protruding from his leg and a laceration along his belly.

“I just remember seeing the black sky and having glass in my body and hearing an officer saying, ‘Are you all right?’” Benson told the AJC. The second time, he woke up in the trauma center at Atlanta Medical Center with a police officer standing at the foot of his bed.

That’s when he learned what had happened.

The officer told him his great-nephew was at Egleston and they were trying to keep the baby alive. “And my heart just dropped,” Benson said.

Benson said he learned the baby had died when he saw it on the news the next day.

“I didn’t know what to think about that at first,” Benson said. “It was the most shocking thing I’d ever heard.”

More pursuits, more risk

The possibility of harm to bystanders is something the GSP policy says troopers should consider before pursuing a vehicle.

The agency’s written policy states that, in every pursuit, a trooper must first consider the seriousness of the initial offense that prompted the traffic stop and whether the threat posed by that offense justifies the threat posed to people who may end up in the path of the pursuit. Sometimes a trooper’s most “professional and reasonable” decision is to end a pursuit in the interest of public safety.

But minimal restrictions on chases and lack of guidance for troopers on when they should be avoided or called off has helped fuel a culture that leads to excessive pursuits that endanger the public, the AJC’s investigation found.

“I think it’s the culture of the agency that has developed that ‘You’re not going to get away from me. I’m the good guy. You’re the bad guy,’” said Geoff Alpert, a University of South Carolina professor who has spent decades researching police pursuits and ways to make them safer. “There’s no gray in it. ‘You run from me I’m going to get you. I’m going to teach you a lesson.’”

Capt. Burns, the GSP spokesman, said in the agency’s written statement that a driver’s responsibility and failure to stop “cannot be overlooked or over-emphasized.” His statement echoed a long-held philosophy by law enforcement to justify dangerous pursuits.

“This is the one act that would alleviate all pursuits and use of force encounters — compliance,” Burns said. “Should the law not be proportionally enforced on those who do not comply, criminals are unchecked, and crime escalates disproportionally and to the detriment of law-abiding citizens.”

National research indicates that calling off pursuits that occur over nonfelony offenses is often the safest alternative. But that seldom happens at the GSP, according to the AJC’s analysis. Although 87% of GSP pursuits in 2023 were initiated over nonfelony violations, with the overwhelming majority stemming from traffic infractions that would otherwise be a citation, only 19% were called off.

The most common reason listed by troopers for calling off a pursuit was because the trooper lost sight of the vehicle they were chasing. That occurred in 12% of all pursuits. In just 1% of pursuits, troopers reported concerns for public safety as the reason for discontinuing the pursuit.

“The cost of all the injuries and deaths is not worth it. Especially when most of these started with misdemeanor offenses or traffic infractions."

The AJC’s analysis found that when troopers called off pursuits, crashes happened less frequently. Only 3% of GSP’s pursuits that were called off for any reason by the trooper resulted in a crash, whereas half the pursuits that were not called off ended in crashes. Alpert said he’s learned over his decades of studying police pursuits that when agencies restrict pursuits it leads to fewer crashes, injuries and deaths.

“It’s the ‘bad guy’ who initiates the chase, but isn’t it the cop who has the immediate decision of whether to continue or stop?” Alpert said.

And when troopers chose to continue pursuits, those decisions also posed significant, potentially grave, consequences for people who had no part in another person’s choice to flee.

The AJC’s analysis of five years of data found that some 523 bystanders were injured in GSP pursuits during that period, while roughly 470 passengers in the pursued vehicles suffered injuries. Together, they account for more than half the people injured in GSP pursuits.

“It’s not just the police officer and suspect who is trying to elude and/or flee. There are other people involved,” said Wendy Hicks, a professor at Ashford University in San Diego who has studied police pursuits nationally.

Hicks’ research, like that of Alpert and others, has found that pursuing someone for traffic violations, even excessive speeding, often endangers the public more than the traffic violation does. Alpert’s research has found that the more high-speed pursuits an agency engages in, the riskier it is for the public.

Pursuit policies should be relatively restrictive, Alpert said, ideally allowing troopers to chase only when there’s a clear and present danger — that is, if a fleeing person escapes, they could harm the public. Many agencies define this danger as the person fleeing has already committed a violent felony or has the means to commit a violent felony. The act of fleeing from police itself shouldn’t be a factor in deciding whether to pursue or not, he said.

The Police Executive Research Forum, a policy think tank, released a study with the U.S. Department of Justice in September that urged law enforcement agencies to limit pursuits or revise their policies to make pursuits less risky.

The 144-page study listed more than 60 recommendations, such as requiring a supervisor’s participation during a pursuit and evaluating training standards, to help agencies improve their pursuit practices. It determined that discontinuing chases, especially those that began over traffic violations, is the most effective way to minimize harm to the public.

According to the PERF study, there is evidence that many pursued drivers will slow down if an officer calls off a pursuit. The study cited researchers that interviewed people who had been pursued by law enforcement and found that about 75% of them said they would slow down when they felt safe. Those drivers specify they would feel safe if they could drive two blocks without hearing a siren or seeing emergency lights flashing.

“You can get a suspect another day, but you can’t get a life back,” Chuck Wexler, PERF’s executive director, wrote in the report’s introduction.

Decision-making part of the risk

GSP doesn’t restrict pursuits at any speed, under any weather or traffic conditions or for any charge. The agency makes no distinction between a traffic offense and felonies when deciding whether to pursue. Experts say that could leave troopers in a lurch when they are deciding whether to discontinue a pursuit.