Georgia prison system engages in deception as crisis builds

U.S. District Judge Marc T. Treadwell had seen enough. The defendants in a long-running civil case had come into his courtroom and repeatedly claimed to have lived up to the terms of a settlement when they clearly had not. He did not mince words.

“The Court has long passed the point where it can assume that even sworn statements from the defendants are truthful,” the judge wrote in an August order.

The target of his frustration: the Georgia Department of Corrections.

Questions about honesty and transparency aren’t new for the state’s largest law enforcement agency. But amid increased scrutiny due to record homicides and other criminal activities in its prisons, GDC officials have taken the lack of candor to a new level. They have repeatedly presented false or misleading information to federal investigators, state lawmakers and even a federal judge, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation has found.

Falsified and backdated documents, false statements and flawed data are some of the tactics the agency has employed in attempting to hide its dysfunction, the AJC found. The GDC also has moved to block access to potentially damaging information.

Through it all, GDC officials have denied that the prison system is in crisis, with Commissioner Tyrone Oliver going so far as to tell state lawmakers that news accounts of undisclosed homicides and record deaths were “propaganda.”

“Is the Department of Corrections being fully transparent with everything that’s going on?” state Sen. Randy Robertson, R-Cataula, asked during an August hearing.

“Absolutely,” Oliver responded.

But evidence suggests that the GDC has played games with the truth.

The most glaring example is when the GDC in March stopped including the preliminary cause of death in its monthly mortality reports identifying each prisoner who had died. That made it difficult to know how many prisoners were being killed and how many had committed suicide. Even in cases in which prisoners have clearly been beaten or stabbed to death, the GDC now lists no initial finding for how those prisoners died — information it had routinely provided for years.

Misinformation was also a theme of a U.S. Department of Justice report on conditions inside the state’s prisons. The report, issued in October, says the GDC refused to release some records and put restrictions on how and when federal investigators could visit prisons. As a result, the investigation became “unnecessarily contentious and lengthy,” the report says. The DOJ also described how in the days before federal investigators visited prisons, the GDC hurriedly fixed buildings that had languished in disrepair.

An even stronger rebuke came from Treadwell, of the U.S. District Court in Macon, when in April he issued a contempt order citing the GDC for making false statements or misrepresentations about its efforts to comply with the 2019 settlement of a lawsuit over conditions in the agency’s supermax prison, the Special Management Unit in Jackson. The GDC’s defiance went on for more than four years, while agency officials were thumbing their noses at the court and never making the changes they had agreed to, the judge wrote.

“As the end of the injunction’s term neared, it became clear to the Court that the defendants, in effect, were running a four-corner offense and had no desire or intention to comply with the Court’s injunction; they would stall until the injunction expired,” Treadwell wrote in his contempt order.

The AJC Prison Corruption Series

Read an ongoing series about Georgia’s prison system from The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Highlights and latest news from the AJC’s prisons coverage

Georgia prison homicides outpacing last year

Georgia prison system engages in deception as crisis builds

Dept. of Justice finds Ga. prisons in chaos, state ‘indifferent’ to violence

Georgia prison corruption: Criminal kingpins operate from the inside

Georgia officials won’t release information on how prisoners are dying

With the contempt order, Treadwell was ending that game. He’d given Georgia the benefit of the doubt for years. That was now over.

Yet even after Treadwell issued his order, the attorneys representing the prisoners in the case obtained documents that again raised serious questions about the GDC’s credibility.

Looking into the unexpected death of the suit’s lead plaintiff, Ricardo Daughtry, the attorneys found records showing that he had attended “table time” outside his cell, a requirement of the settlement for prisoners to spend time in a common room at a restraint table. But, in fact, by then he had already been pronounced dead.

“To state the obvious: there is no way R.D. could have participated in out-of-cell time after his death,” the attorneys wrote in a court filing.

‘Failure to comply’

The Special Management Unit case began in 2015 when a prisoner filed a handwritten lawsuit challenging his placement in one of the unit’s solitary-confinement cells. The unit, commonly known as the SMU, is where the GDC houses some of its toughest prisoners, many of whom are there because they committed new crimes while serving their sentences.

The prisoner who filed the lawsuit, Timothy Gumm, lived in a cell the size of a parking space for five years, with almost no time outside, after he was accused of being part of an escape attempt. Gumm denied the allegations, and a disciplinary report related to the incident was overturned after the case was reviewed by higher-level prison officials. Even so, Gumm remained locked away in the SMU, losing 50 pounds from not getting proper food and suffering physical, mental and emotional anguish and psychological trauma, he wrote in his initial legal claim.

A magistrate judge felt Gumm’s arguments had merit and appointed highly regarded attorneys from the Southern Center for Human Rights to represent him and others in the unit.

A leading expert on prison conditions and solitary confinement, Craig Haney, was brought in to study the unit, and he described the SMU as “one of the harshest and most draconian” solitary confinement facilities he had ever seen. He described conversations with those held in the unit, took pictures and included chilling accounts in his report.

“The atmosphere inside E Wing was bedlam-like, as chaotic and out-of-control as any such unit I have seen in decades of conducting such evaluations,” Haney, a psychology professor at the University of California-Santa Cruz, wrote. “When I entered this housing unit I was met with a cacophony of prisoner screams and cries for help. The noise was deafening.”

The findings resulted in a settlement that called for sweeping changes. But what emerged exposed the willingness of the GDC to mislead a judge, make false statements in court and falsify documents.

Ahmed Holt, an assistant commissioner and former warden who has spent 23 years with the GDC, provided much of the testimony the agency used to make the case that it had complied with the settlement. In his 100-page contempt order, Treadwell made clear he found little of it believable.

Holt swore in 2022 that prisoners were getting time out of their cells at tables. Evidence showed they were not. Holt said required educational programming was provided via televisions in cells. In fact, two entire wings of the unit had no TVs. Holt claimed that the unit had adequate staffing. Evidence strongly suggested otherwise.

“Even if Holt were a credible witness, and he is not, his vague excuses, with no supporting evidence, do not excuse the defendants’ failure to comply with the injunction,” the judge wrote in the order.

Treadwell also came down hard on the GDC for falsifying records purporting to show that prisoners were receiving regular reviews to chart their progress toward leaving the SMU.

The contempt order cited the testimony of a counselor who said she refused to sign review forms because she was asked to sign for prisoners who weren’t present. The counselor, Kendra McBurnie, testified that other counselors signed for inmates on her caseload when she wouldn’t do it.

Prisoners testified that they were instructed to sign the forms but not date them, “apparently,” Treadwell wrote, “to allow backdating so that it would appear that a review hearing was timely held.”

The case is still pending, and the judge appointed an independent monitor to report on compliance.

Asked by the AJC about Holt’s conduct in the case, the GDC said it believed he had testified accurately about one facet of the settlement — computer tablets that were supposed to be provided to prisoners but never were. The GDC’s response to the AJC’s questions did not address the many other issues that caused the judge to castigate Holt, one of the agency’s highest-ranking officials, for his misrepresentations.

In spite of the contempt order and its repeated examples of the GDC’s failure to comply with the settlement, an agency spokesperson asserted that the GDC was in compliance.

“GDC continues to maintain that it has complied and continues to comply with almost every provision of the Settlement Agreement,” the spokesperson, Lori Benoit, wrote in an email.

Less than two months after Treadwell issued his blistering contempt order, Daughtry, 40, was found dead in his cell. Although GDC policy required that he be checked every 30 minutes, records obtained by his attorneys show that no one looked in on him for nearly seven hours before his body was discovered.

Moreover, not only do prison records show Daughtry attending “table time” after he was dead, they also show him refusing to take part in recreation or the book cart.

The GDC has released almost no information on Daughtry’s death, even to his attorneys, citing a pending autopsy and ongoing investigation. Six months later, his death remains a mystery.

Shaping the narrative

Throughout 2023, the AJC exposed deep failures within the Department of Corrections. Widespread corruption has plagued the prison system, the AJC found, with hundreds of GDC employees arrested and fired for smuggling in drugs and other forms of contraband. The AJC also detailed extreme understaffing, extensive illicit drug use by inmates, record numbers of homicides and suicides and large criminal enterprises run by prisoners that victimized people on the outside — even ordering that some be killed.

The AJC has continued to expose failures within the GDC throughout 2024, including findings of extreme violence, stunning homicides that suggest a complete breakdown in security and lawsuits over wrongful deaths that have cost Georgia taxpayers millions.

GDC officials have repeatedly brushed off suggestions that the prison system is in crisis. But in the wake of the coverage, members of the Georgia General Assembly began asking questions.

The state Senate in March appointed a study committee to explore every aspect of the system and come up with recommendations for consideration in the legislative session that begins in January. In July, House Speaker Jon Burns, R-Newington, created a special subcommittee to be prepared to act on prison recommendations.

Appearing before the Senate committee in August, Oliver, the GDC commissioner, repeatedly described critical news articles as propaganda, including coverage of his decision to stop releasing initial cause of death information in monthly mortality reports.

Oliver testified that the decision was driven by a desire for accuracy and wasn’t an effort to hide information.

In defending his decision to the AJC earlier in the year, Oliver said the GDC’s public reports would be updated once coroners made the official determinations for prisoners’ causes of death, which can take as long as a year. However, when the AJC asked for the final death determinations from 2022 and 2023, GDC General Counsel Jennifer Ammons declined the request, saying the agency doesn’t compile such a report and therefore didn’t have to create one for the public.

Additionally, when the AJC and others request incident reports for prisoner deaths, the GDC routinely blacks out entire pages, citing a variety of exemptions in the Georgia Open Records Act. In that way, the reports contain vastly less information than those routinely released by other law enforcement agencies and earlier GDC administrations.

At the August hearing, Oliver told lawmakers that the overall number of deaths within the prison system this year had been fairly typical. While he acknowledged that there were more homicides in 2024 than in prior years, he pushed back on the idea of a crisis.

“The propaganda out there that, you know, it’s out of control and it’s been, you know, we’re hitting all these record highs,” he said. “When you look at the total number of deaths, it’s been remaining pretty consistent.”

The numbers tell a different story. Deaths in the prison system are up across the board. By the end of October, more prisoners had died — 270 — than in each of the previous three years, according to an AJC analysis of the GDC’s mortality reports. Georgia prisons are even on track to see more deaths in 2024 than in even the worst year of the pandemic, 2020, when COVID was responsible for 72 of the 281 inmate deaths listed by the GDC, according to an AJC analysis of mortality reports and public death records.

The AJC has also determined — using coroner reports, other public records and information from families — the identities of at least 51 prisoners so far in 2024 who have been victims of homicides. The total could be significantly higher, with many suspicious deaths still under investigation. The 2024 homicide total to date tops last year’s record of 39, which was itself a big jump over prior years. GDC facilities had only eight homicides for the entirety of 2017 and nine for all of 2018.

“Nobody expects that there should be a death rate of zero. Everyone understands that prisons are hard places to run and house a lot of people, so there will be mortality that the administration has to grapple with,” said Aaron Littman, an assistant professor at the UCLA School of Law and the faculty director of UCLA’s Prisoners’ Rights Clinic. “But what we have (in Georgia) is a stunning level of it accompanied by a stunning refusal to pull back the curtain. That’s pretty concerning.”

In its response to this story, the GDC pushed back on the notion that it was covering up anything related to in-custody deaths. Although it doesn’t identify which prisoners are believed to be victims of homicides or name prisons where the deaths occurred, GDC said it has released the number of cases so far this year being investigated as homicides, including in August to the Senate committee studying the system. “How can you assert that we are not transparent when we presented those numbers in an open, public meeting?” agency spokesperson Benoit said in her email, referring to legislative testimony.

She went on to say that the GDC had provided voluminous amounts of information to the AJC over the past two years and had demonstrated that the agency and its leadership are transparent about what’s happening inside the prison system.

Georgia’s Special Management Unit

The 192-bed unit known as the SMU is Georgia’s supermax prison. The unit is located in Jackson on the same prison complex as the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison, which is the first stop for most male prisoners entering the system. The GDCP complex also includes Georgia’s Death Row.

The SMU is the state’s most restrictive prison. At all times, prisoners are locked inside their cells, outdoor cages, shower stalls or visitation booths. Or, they are handcuffed to tables or placed in cuffs and leg irons to be moved around.

Everyone in the unit is in solitary confinement. The unit has six wings with 32 single-man cells in each wing. An incentive-based program is supposed to allow those who meet goals to leave the unit, but plaintiffs in a long-running lawsuit over conditions at the SMU say the program often doesn’t work as described.

Unfounded and unsubstantiated

In its October report, the Department of Justice described conditions in Georgia’s prisons as horrific and inhumane.

“People are assaulted, stabbed, raped and killed or left to languish inside facilities that are woefully understaffed. Inmates are maimed and tortured, relegated to an existence of fear, filth and not so benign neglect,” said Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke in announcing the findings.

The DOJ was particularly pointed in its criticism of how the GDC deals with allegations of sexual assault, which are supposed to be investigated in accordance with the federal Prisoner Rape Elimination Act, commonly known as PREA. “Defective at every level” is how the DOJ described the GDC’s investigations.

Among the cases cited by the DOJ was the attempted rape of a transgender woman. It was ruled unfounded due to a lack of penetration even though the perpetrator entered the victim’s cell with his penis in his hand. Another was the case of a prisoner who claimed to have been raped at knifepoint by his cellmate. It was ruled unsubstantiated even though the victim was found to have bruising and seminal fluid in his anal area.

That didn’t stop GDC leaders from touting their PREA procedures when state Rep. Scott Holcomb brought up the subject at the first meeting of the special House subcommittee on state prisons on Nov. 13.

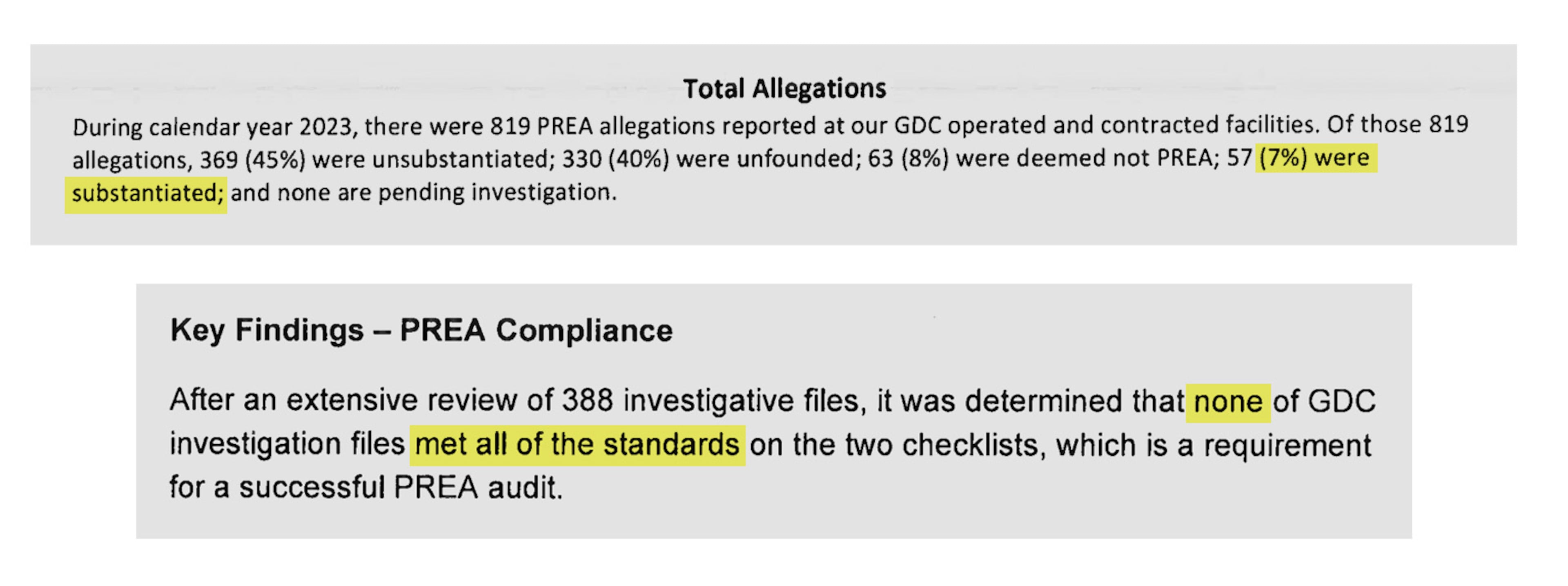

Holcomb, D-Atlanta, wanted to know more about the GDC’s data for 2023, which showed that only 7% of the 819 PREA allegations it investigated that year had been substantiated. How, he wondered, were so many cases unfounded and unsubstantiated?

Holt, the assistant GDC commissioner whose credibility was questioned by a federal judge, quickly explained that all GDC facilities undergo an assessment for PREA “from the federal level each year” and all had “passed successfully.” Many, in fact, have received “high ratings or accolades,” he said.

Oliver then noted that the GDC investigates all alleged PREA offenses and that its agents receive the same training as those who work for the GBI.

Neither mentioned the data or any concerns about the investigations behind it.

In fact, GDC officials learned that their PREA investigations were flawed in May 2022 — more than two years before the DOJ issued its report — when consultants retained by the agency made that very point.

The consultants, PREA Auditors of America, said they examined 388 of the agency’s investigative files and determined that none met the law’s standards. The “discrepancies” cited in the report, recently obtained by the AJC from the GDC in response to an open records request, included instances in which witnesses were identified but not interviewed and cases in which the final outcomes were decided on the investigators’ opinions and not the evidence.

Brenda Smith, a law professor at American University in Washington, D.C., who was one of the members of the commission that developed the law’s language, said 7% is a “very, very low” percentage of substantiated cases. But if a prison system relies on flawed investigations, it will have flawed data and a false picture of how it deals with sexual misconduct, she said.

“People are trying to keep their jobs, so if I’m the commissioner of corrections, I’m really not out there trying to put out that I’m having all these incidents,” she said. “But what you can do is say, `We have discovered things,’ in the same way you talk about graft, in the same way you talk about people being honest in the hours they claim to be working. It’s all about integrity, and this is another breach of integrity — maybe the greatest one, which is harming people for whom you have legal responsibility.”

In response to the DOJ’s investigation, GDC officials said the prisons operate in a manner that exceeds constitutional requirements. The DOJ’s findings, the GDC said, “reflect a fundamental misunderstanding of the current challenges of operating any prison system.”

Moving ahead

When the General Assembly convenes in January, lawmakers must decide what portrait of the Department of Corrections they see. Will they believe an agency that says it’s on the right path and brush off reports of crisis as propaganda? Or will they act as if it’s a failing agency that leaves prisoners and the public at risk?

If lawmakers look at the most troubled part of the system, they will learn that at most of Georgia’s high-security prisons two-thirds of the correctional officer positions are unfilled. The AJC has reported on fatal beatings that go on for hours, criminal enterprises that continue to run unchecked and mental health units where suicides and homicides are frequent and kept hidden or unexplained to both the public and the families of those who died.

Advocates say lawmakers should insist on honesty and transparency from an agency that spends more than $1.4 billion a year, especially when it comes to the record levels of deaths.

“The GDC has gone from publicizing deaths — as they should as a state agency — to shielding the public from the unprecedented amount of death in our prisons,” said Atteeyah Hollie, deputy director of the Southern Center for Human Rights and one of the attorneys working on the SMU case. “Having abandoned its previous commitment to openness and transparency, Georgia now conceals the fact that its prisons are incapable of providing for people’s basic needs. We should not allow state agencies to hide in the shadows.”

She said transparency is particularly important now, given what’s going on inside the prison walls.

“I don’t think I’ve seen during my time at the Southern Center — and I’ve been here for almost two decades — this level of suffering in Georgia’s prisons or this level of indifference by the agency charged with their care,” Hollie said.

Haney, the expert who initially evaluated the SMU, said it’s disheartening and frustrating that the GDC didn’t improve the shocking and deplorable conditions he saw in the unit and then wasn’t truthful in court.

“You would think public officials ought to have some allegiance to the truth,” he said. “If they’re not doing things that they’re supposed to do, they can offer explanations for why they’re not, but they at least need to be honest about what’s happening. And instead, apparently, the memo is ‘Just lie until you get caught.’”