Georgia inmate with ‘nothing to lose’ keeps killing

Editor’s note: This story, first published on Dec. 16, has been updated with information on a Dec. 20 court hearing.

Of all the inmates at Augusta State Medical Prison in the spring of 2020, no combination may have been more combustible than Daniel Luke Ferguson and Eddie Gosier.

Ferguson had a well-known reputation for violent attacks on fellow inmates. Gosier had physical handicaps and the stigma that comes with being in prison for sexually assaulting a teenage boy.

Yet officers monitoring the medical prison’s inmate population had no reservations about moving Ferguson into Gosier’s cell. It was the kind of decision made nearly every day by those running Georgia’s prisons. And it was a decision that cost Gosier his life.

As violence has surged throughout the Georgia Department of Corrections in the past three years, the face of it just might be Ferguson. Sentenced to prison at 18 for killing a neighbor in Walton County, in the 14 years since then he has killed two fellow inmates and tried to kill another.

Those crimes, examined in detail by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, provide one of the starkest portraits to date of the state prison system. They show how a dangerous inmate —marginally supervised and knowing justice won’t be particularly swift or meaningful — can kill with little consequence from prison authorities or courts.

“He is a serial killer who will kill again if the opportunity presents itself,” said Gosier’s sister, Lena Thomas. “And he has nothing to lose. Nothing to lose.”

Ferguson’s first victim was a neighbor, 94-year-old Tom Daniel. After pleading guilty to murder in 2008, Ferguson was sentenced to life in prison. He couldn’t receive the death penalty because he was 17 when he committed the crime.

In 2011, Ferguson slashed the throat of a cellmate at Georgia State Prison with a razor blade tied with string to a toothbrush handle. The cellmate, Travis Boyd, was seriously wounded but survived. Although a GDC incident report extensively described the attack and named Ferguson as the aggressor, Ferguson was not charged.

Less than two years later, Ferguson strangled Damion MacClain, an inmate who occupied a nearby cell at Hays State Prison. That case, originally charged as murder, was resolved when Ferguson pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter. Twenty years were added to his life sentence.

Ferguson had agreed to plead guilty to the murder of Gosier, found strangled with a bed sheet on the very day in May 2020 that he and Ferguson were put together in a cell, and he was due to be sentenced Tuesday. But the plea — yet another life sentence — was set aside by Judge J. Wade Padgett after Ferguson questioned whether he’d received proper legal representation.

Ferguson, participating via video conferencing, initially said he was guilty and accepted the plea. But the hearing changed abruptly when Padgett asked Ferguson whether he’d received an adequate defense. In response, Ferguson said he was unhappy that his attorney, Terrence Theus of the Columbia County public defender’s office, hadn’t consulted an expert in post-traumatic stress disorder.

Ferguson’s statement came minutes after a Columbia County prosecutor told the court that Ferguson claimed to have told officers he didn’t want to be in Gosier’s cell but was “forced” in anyway. According to the prosecutor, Amber Brantley, Ferguson claimed he was using meth and suffered “flashbacks” to being molested as a child when Gosier made a sexual advance.

As a result of Tuesday’s proceeding, the case will now go to trial, likely early next year. Theus did not respond to phone messages from the Journal-Constitution.

Since being charged with Gosier’s murder, Ferguson has been in solitary confinement at the GDC’s Special Management Unit in Butts County, standard procedure for inmates charged with serious crimes.

Ferguson’s mother, Leah Ferguson, declined to be quoted extensively except to say her son isn’t violent by nature. Rather, she said, he has become hardened by life inside the prison system. He has frequently been forced to defend himself, she said.

“Since he was a young man, he’s lived in the Georgia Department of Corrections, and it’s not a pleasant place,” she said.

Although Ferguson is white and his victims Black, the AJC could find no evidence that Ferguson had a history of racist remarks or that the killings were racially motivated.

A violent environment

Whatever his motives, many believe that long-standing factors — overcrowding, understaffing, indifference, security lapses — make Department of Corrections facilities breeding grounds for murder.

“You have people with nothing to lose on top of no supervision and idle time,” said Jennifer Bradley, who has become an outspoken critic of conditions inside GDC facilities since her son, Carrington Frye, was murdered at Macon State Prison in March 2020.

Georgia corrections advocate Susan Sparks Burns said officers and supervisors think nothing of putting nonviolent or otherwise vulnerable inmates in cells with those known to be dangerous and then looking the other way. Putting a child molester in a cell with a known killer represents the height of that dysfunction, she said.

“All you have to do is think about it,” she said.

Several recent lawsuits detail in graphic terms the GDC’s failure to deal with offenders bent on violence.

“[Ferguson] is a serial killer who will kill again if the opportunity presents itself. And he has nothing to lose. Nothing to lose."

One alleges that an inmate at Macon State Prison, Bobby Edward Lee Jr., was strangled to death by his cellmate, Tony Cary Mitchell, shortly after they were placed together in a cell in July 2020. The officers on duty knew that Mitchell had previously killed a fellow parolee at a Fulton County halfway house in the same manner, yet they took no action when Lee pleaded for protection, the suit claims.

Another contends that Jerry Lee Brown, an inmate at Johnson State Prison, died in November 2020 after an officer on duty ignored screams and pleas from other inmates as Brown was being violently attacked by his cellmate, a convicted murderer. Brown’s body was later discovered with his arms and legs tied, a sharpened plastic object in one eye and a metal object in an ear, the suit states.

Brown’s daughter, Ashley Brown, who filed the suit along with her brother, said the main objective is to shine more light on what’s happening within the prison system.

“It’s not about money,” she said. “It’s about stopping what’s going on in there. At some point, the system has to be held accountable.”

GDC spokesperson Joan Heath did not respond to questions from the Journal-Constitution about Ferguson. However, she said the agency is diligent in maintaining its commitment to staff and inmate safety.

“Extensive protocols are in place to aid staff in proactively addressing potential incidents, “ Heath wrote. Those measures, she said, include the recent expansion of mental health services and behavioral counseling. GDC also has added what she called “an enhanced offender assignment system which optimizes assignments using data and start-of-the-art methodologies based on a variety of inmate and institutional factors.”

Murder across the road

The first time Ferguson killed, he did it just a few steps from his home. Living with his parents on a lonely stretch of Jacks Creek Road east of Monroe, he entered the house across the street and robbed and killed Daniel, its lone occupant.

The 94-year-old was found to have two gunshot wounds to his torso, neither of which was fatal, and another to the back of the head that killed him.

At the sentencing, prosecutor Eric Crawford revealed that Ferguson admitted to shooting Daniel when the elderly neighbor woke up during the robbery and retrieved and cocked his own gun. According to Crawford, Ferguson claimed Daniel was in pain from the first shots and said he was “ready to meet his Lord,” so Ferguson shot him again, this time in the head using the old man’s gun, and then took $170 from his wallet.

Crawford also told the court that Ferguson had admitted he was a meth user and that the drug had hampered his ability to remember exact dates.

Crawford, now a criminal defense attorney, said Daniel’s murder is one he remembers well because it was so senseless.

“The whole thing was a complete shock to me,” he said. “(Ferguson and Daniel) knew each other well, and (Ferguson) seemed genuinely remorseful at the time of the plea.”

Three years into his prison sentence, Ferguson was in a cell at Georgia State Prison with Boyd, sentenced for a lengthy history of drug-related convictions.

Just hours after being placed there, Ferguson attacked. Boyd survived after being transported by helicopter to a hospital in Savannah.

When questioned about the matter by officers, Ferguson refused to provide a statement, according to the incident report.

In a recent letter to Burns, Boyd wrote that he still can’t explain why Ferguson attacked.

“Honestly as for him attacking me … I don’t really understand why?” he wrote. “I never done anything to him nor do I even know him.”

There’s nothing in the GDC report to explain why the assault, which could have been considered attempted murder, did not lead to criminal charges.

Ferguson was then moved to Hays State Prison, which the GDC says manages “some of the state’s most challenging offenders.” During an eight-week period starting in mid-December 2012, four inmates at the prison were murdered and two guards stabbed. MacClain, 27, was among the murder victims.

“Honestly as for him attacking me … I don't really understand why? I never done anything to him nor do I even know him."

Ferguson strangled him during a fight late on Christmas night. Other inmates reportedly were involved in the melee, but Ferguson was the only one charged.

A lawsuit filed by MacClain’s mother, Rahonda MacClain, alleged that her son, serving time for armed robbery, was housed in an area where the locks on cell doors weren’t functioning, making it possible for Ferguson to move freely despite his history of assault.

She died unexpectedly five months after filing the suit, leaving her brother, Lysander Turner, to become the plaintiff. He settled with the state for $350,000.

Another killing

After the MacClain killing, Ferguson was placed in solitary at the Special Management Unit, then moved to Augusta State Medical Prison, which houses inmates seeking medical attention as well as others requiring close security.

That prison has long been plagued by security issues, some of which were spotlighted by the facility’s former medical director, Dr. Timothy Young, in a whistleblower lawsuit. The suit was filed in 2018 and settled three years later with the state paying $300,000.

In October 2019, Ferguson was found in an unauthorized area of the prison and refused to leave, forcing officers to Tase him. Then, when he refused to put on his handcuffs properly and return to his cell, he was hit with pepper spray.

Seven months later, Ferguson was placed in a cell with Gosier, 39, in the security wing.

At the time of his death, Gosier had served eight years of a 20-year sentence for sexual assault of a 14-year-old boy. Gosier reportedly assaulted the boy after asking him to come to his house in Quitman to help move furniture.

The crime was another chapter in a troubled life. Born with club feet and a condition that didn’t allow him to straighten his fingers, Gosier struggled to walk normally even after surgery, his sister said.

Thomas, who lives in Tifton, said she understands how people can react to her brother’s crime, but officers should have known he was someone who could be particularly susceptible to violence.

“People who commit crimes against children are targeted,” she said. “Everybody in prison knows it. And on top of that, he had physical disabilities.”

Brantley’s statements at the sentencing hearing added to a scant public record. Court documents and the GDC incident report give few details about Gosier’s slaying. There is no video, according to GDC.

Now the question is what more can be done to Ferguson if he’s found guilty of yet another murder.

The plea deal laid out at the hearing would have meant life with the possibility of parole. In theory, that would have pushed his eligibility date out to 30 years from this month. Would that have any impact?

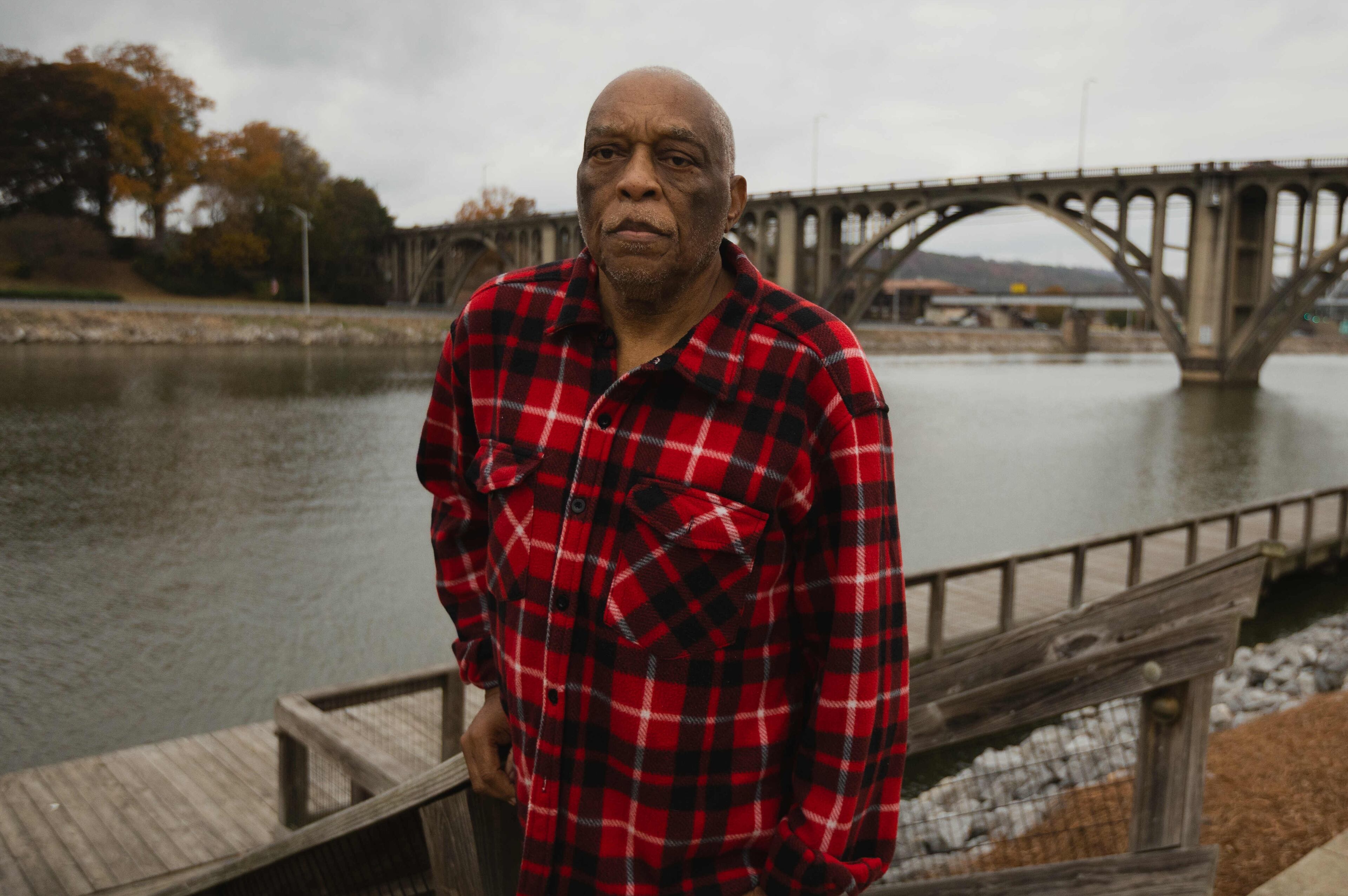

Thomas isn’t sure, but she hopes there can be closure for a situation that, her brother’s issues aside, should never been allowed to happen.

“He went to prison for what he went to prison for,” she said, “but he was not sentenced to die.”

Investigative reporter Danny Robbins can be contacted at AJCInvestigations@ajc.com.