Charges to be dropped against Carroll County murder suspect after 73 years

Clarence Henderson will get his day in court next month in Carrollton where Superior Court Judge Erica Tisinger will hear a motion to drop charges against him for the murder of Carl “Buddy” Stevens, Jr.

The motion, scheduled to be heard in open court March 2, comes more than seven decades after police arrested Henderson, setting the Black sharecropper on a years’ long journey through the Jim Crow justice system of segregation-era Georgia.

Coweta Judicial Circuit District Attorney Herbert Cranford filed the motion Jan. 23 after reviewing the case at the request of Henderson’s great-grandson, Atlanta resident Brandon Henderson.

“I’m very thankful for everybody who is involved,” Brandon Henderson said after learning the charges against his ancestor are to be dismissed. “I can’t express my gratitude in words. I’m just thankful that this day is here.”

Clarence Henderson, who died more than 40 years ago, was tried and convicted three times by all-white juries on charges of having killed Stevens. Each time the Supreme Court of Georgia overturned the convictions citing a lack of evidence in the case, but the charges were never dropped.

The case was well known in Carrollton for generations, but had faded from memory in recent decades until a book investigating the Stevens murder and Henderson prosecution was published last year. Although Henderson, the victims, lawyers and witnesses have all passed away, Cranford said there are good reasons for formally dismissing the charges now.

“Pursuing justice, upholding the law, and maintaining the trust of the community all include dismissing charges as much as they do prosecuting charges,” he wrote in the motion.

The move comes amid a reconsideration of historical past injustices, such as monuments erected to memorialize forgotten lynchings and books and podcasts that investigate the South’s history of racial discrimination through the criminal justice system.

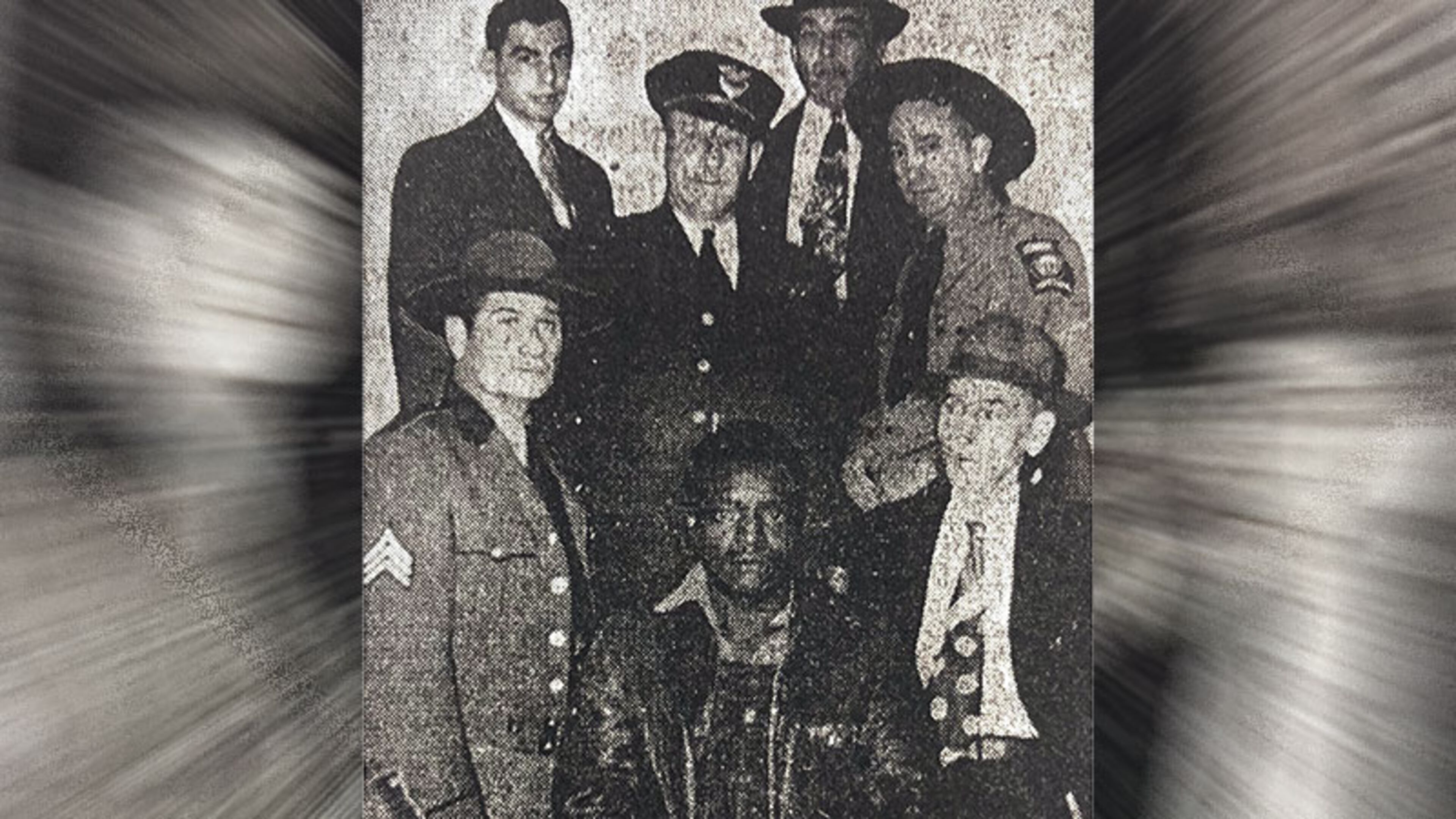

Stevens, a white 22-year-old Army veteran, was killed on Oct. 31, 1948, defending his girlfriend, Nan Turner, from a would-be rapist suspected in several earlier attacks stretching over the summer of that year. Turner could not give a description of her attacker but told police he “sounded like a Negro,” according to court records and contemporary press coverage.

The murder shocked the community and led to a statewide manhunt, but more than a year passed before police arrested Clarence Henderson. Henderson had no connection to the crime and no witness put him at the scene, but investigators said he owned the suspected murder weapon for a narrow window of time long enough to have been the culprit.

Henderson, who died of natural causes about 40 years ago, denied owning the gun, and expert witnesses disagreed over whether the gun actually fired the fatal shot.

Brandon Henderson said the pending dismissal of the charges against his great-grandfather validates “what we’ve known for far too long.”

In his motion, Cranford wrote that the state’s case rested on circumstantial evidence, including a series of witnesses who testified that they saw Henderson in the weeks prior to the murder with a gun similar to the one believed to have been used to kill Stevens. But no witness placed Henderson at or near the scene and Henderson maintained his innocence in two written statements taken after his arrest.

The evidence that Henderson was the culprit was never there, Cranford wrote. “Through three jury trials, that never changed, and still has not changed.”

Henderson’s three guilty verdicts were each overturned by the Supreme Court of Georgia in the early 1950s, which sent the case back to Carroll County for retrial. The trials were held years before a number of important U.S. Supreme Court precedents that now protect defendants from abuse. If Henderson was in the same position today, the state could not retry him under the modern interpretation of double jeopardy under the Fifth Amendment, Cranford wrote.

“The District Attorney understands the Henderson family’s desire to have the name of their forefather cleared of the charge of murder, and believes most families in the Coweta Judicial Circuit would be similarly motivated in similar circumstances,” Cranford wrote.

Aside from members of Henderson’s family, Cranford wrote that unrelated members of the community have supported the review.

“The District Attorney has been contacted by black citizens and white citizens, young and old, to support the decision to review this case,” he wrote. “Communication with the District Attorney regarding the decision to review this case has been nearly unanimous in support of doing so.”

Cranford told the AJC he wanted to hear from relatives of Stevens and Turner as well, but in his motion said he never heard from anyone. Stevens was the only child of Charlcie and Carl Stevens Sr. and had no children of his own. Turner married a couple of years after Buddy Stevens’s death and moved out of Carrollton, according to records.

While the motion finally removes Henderson as a suspect in the cold case, Cranford wrote that if evidence were available, he would pursue other suspects.

“If the state currently had the ability to determine who murdered Carl Buddy Stevens, the pursuit of justice would demand doing so to provide the truth to the victim’s family and to the community, even if the killer is long dead,” he wrote.

Such a revisit is unlikely. While the county still has the gun suspected of killing Stevens and a 9 mm bullet taken from his leg following the murder, little else exists that would conclusively point to a possible killer.

Our reporting Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigative reporter Chris Joyner spent years researching the murder of Carl “Buddy” Stevens, Jr., and the trials of Clarence Henderson for the book “The Three Death Sentences of Clarence Henderson: A Battle for Racial Justice at the Dawn of the Civil Rights Era,” published in 2021 by Abrams Press. After publication, Joyner continued to investigate the unresolved charges against Henderson, leading to an effort to dismiss them posthumously.