Brawls, disorder mar Georgia boot camp for teens

A massive brawl broke out on a parade ground at Fort Gordon in Augusta one afternoon last fall, when about 70 teenage recruits of the Georgia National Guard’s Youth Challenge Academy slugged it out. Some used homemade weapons, including metal shanks, crudely sharpened toothbrushes and tube socks filled with metal padlocks.

Overwhelmed, the academy’s staff — most former military drill instructors — called for help, summoning the military police to break it up and ambulances to treat the injured. Two boys were taken to the hospital, one with a concussion, the other with bruised ribs. Others were treated on base after the Oct. 13 episode and sent back to barracks where cadets were placed on lockdown.

Within 24 hours of the brawl, a second melee involving more than two dozen teenagers broke out in one of the barracks and senior military leaders shut down the five-month boot camp in its first week, sending all 170 cadets home and barring them from Fort Gordon for a year. The violent week marked a debilitating breakdown of order for the state program that for three decades has helped at-risk youth complete high school education in an atmosphere of military discipline.

Since the shutdown, parents have been given little explanation from the National Guard about how the camp spiraled out of control so quickly. But an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation uncovered leadership failures and mismanagement by state officials who oversaw a program plagued by a history of violent episodes, of which the October melees were the largest.

Leaders rushing to meet a new enrollment quota last fall skipped their normal vetting process. That led to a failure to properly screen recruits for behavioral and mental health challenges, leaving the program’s small staff with the task of dealing with uncooperative and violent youths who were only later determined to be “high-risk” candidates, the AJC investigation found.

And once the academy devolved into chaos and violence, the National Guard’s program leaders made a concerted effort to sidestep accountability and shift blame solely to the teenage cadets without accepting any responsibility themselves, the AJC found after reviewing hundreds of pages of records, internal communications and government reports obtained through Georgia’s Open Records Act.

Jessica Donaldson, who sent her 16-year-old son, Tristan Hill, to the academy, was one of more than a dozen parents and students from the fall class that the AJC interviewed for this story. They provided similar accounts, expressing a sense of betrayal from a state program that attracts families with the promise of supervision and structure to help get their struggling teens back on the road to a successful life.

“I was sold a complete lie,” she said in a recent interview.

Donaldson and other parents said the academy’s administrators had assured them at the Oct. 10 drop-off day that their children would be safe during the five months away from home. Just days after the camp began, parents received an urgent call to return to the Augusta area and pick up their children who came home with stories of violence and trauma.

State leaders, including Gov. Brian Kemp, Adjutant General of Georgia, Maj. Gen. Thomas Carden Jr. and leaders Georgia’s YCA program, either declined the AJC’s interview requests or ignored them altogether.

Frustrated by the state’s lack of answers, Donaldson took her concerns to U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-Ga. in early December. When Ossoff’s staff asked the Georgia National Guard for information, Deputy Adjutant General Joe Ferrero wrote to the senator on Dec. 27, blaming a group of “belligerent, combative, and violent” students for the breakdown.

“Ft. Gordon leadership and our YCA staff jointly determined that the class should be canceled and the students sent home,” he wrote.

Ferrero said Donaldson was “rightly upset” that students were threatened and harmed, and the camp was shut down.

While acknowledging unspecified “lessons learned” from the fiasco, Ferrero did not share with Ossoff the series of missteps by program administrators that preceded the violence. Ferrero also downplayed the camp’s history of violent incidents.

“Such disturbances typically involve just a few students, and our staff intervenes, separates them, and gets the situation under control,” Ferrero wrote.

Word of the day: Chaos

Problems with the Fort Gordon camp began immediately when large numbers of unscreened applicants showed up at a public park pavilion in Martinez for orientation on Oct. 10, creating confusion, long lines and delays.

Lines snaked out of the building as parents tried to fill out forms and students had their bags inspected for contraband.

“The word of the day describing the intake process was: chaos,” staffers wrote in an after-action review obtained via open records request.

Camp Director Jarvise Reid later said she had orders to increase the number of applicants, even if it meant not screening until they got on campus. In an Oct. 25 email to Wallace Steinbrecher, state director of the Youth Challenge Academy, Reid said that meant they let students in without reviewing “critical documents” about their backgrounds.

Those missing documents included school disciplinary and mental health records and federally required plans on how to accommodate students with learning disabilities, she wrote.

One of the notes in the after-action review indicated 37 high-risk students were not interviewed at intake.

The tumult of that orientation day wasn’t what many parents expected from a military operation. Brinsina Copeland said the disorder dampened some of the excitement when she dropped off her 17-year-old son, Devonte Wright, that day.

“I started to have mixed feelings,” said Copeland, who lives in Clayton County. “You come into an operation it’s supposed to be on point, but it was so much chaos. It was not any order at all.”

An incomplete record

The YCA program, created in 1993 by Congress, operates camps in 28 states, Washington, Dap., and Puerto Rico.

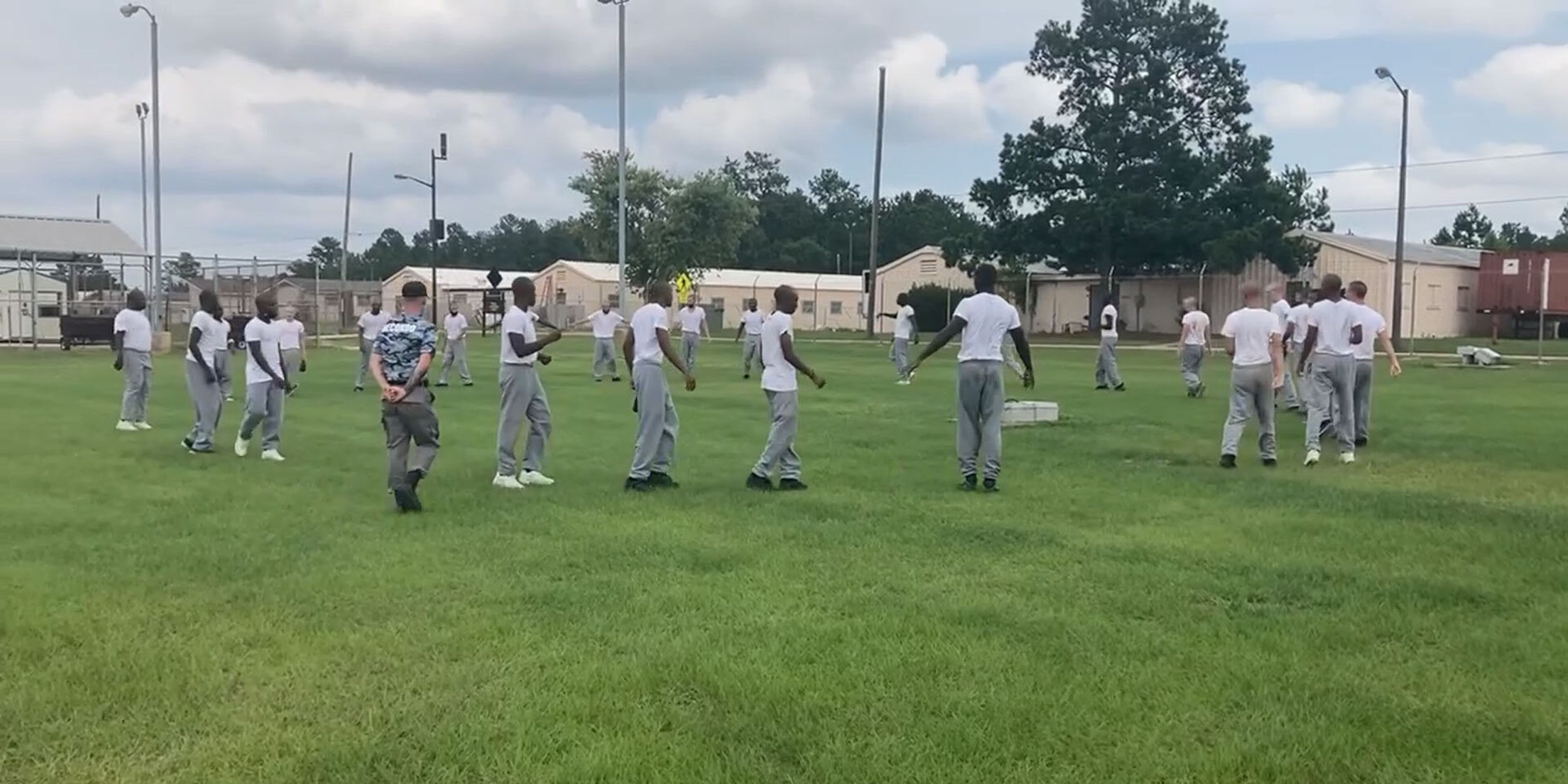

It is funded through the U.S. Department of Defense but administered by the states through the National Guard. The idea is to give at-risk students, ages 16 to 18, life skills, counseling, job training and academic instruction through the lens of a quasi-military boot camp.

In Georgia, the YCA has academies at Fort Gordon and Fort Stewart, about 40 miles southwest of Savannah, attracting hundreds of teenagers each year who live in military barracks with classmates. Georgia’s program boasts that it has had 18,500 graduates over the past three decades.

The program does not track the long-term success of its students, a fact the RAND Corp. has cited in a national study of the YCA as a problem with judging whether the program meets its objective. Anecdotally, many who complete the academy do benefit from the experience. But the program in Georgia has a history of serious problems as well.

In March 2020, an AJC investigation into the academy at Fort Stewart found the camp’s adult platoon instructors — known as cadre — physically abused cadets and sexually harassed female staff, aided by administrators who covered up the misconduct by reprimanding whistleblowers who came forward.

Our reporting

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution received email tips and phone calls from concerned parents in the days after the shutdown of the Fort Gordon Youth Challenge Academy in October. A team of journalists spent months interviewing parents and their children, requesting and reviewing hundreds of pages of records, and pressing for answers from state officials. Three years ago, the AJC went through a similar process for a multi-part series on the Youth Challenge Program at Fort Stewart, a program marred by sexual harassment claims from state and abuse accusations from students. The AJC will continue to follow this important story. If you have additional information on this story, contact reporter Chris Joyner at chris.joyner@ajc.com.

Some cadets reported being choked or slammed to the ground by cadre in violation of the program’s own rules, according to records.

Carden, whom Gov. Kemp appointed to lead the Georgia National Guard, acknowledged the problems but defended the program.

“The only way for me to drive risk to zero in that program is to not have it,” he said in a 2020 interview with the AJC.

Shortly after the investigation published, Georgia’s Youth Challenge Academy sites shuttered amid the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, the program has struggled to regain its pre-COVID enrollment levels and graduation rates have been significantly lower, according to state data.

A violent past

Fort Gordon’s YCA program has had its own history of trouble, the AJC has learned. Incident reports for the past two years detail massive fights, violent outbursts and serious mental health issues among cadets requiring the intervention of military police, ambulances or both, including:

- A fight in March 2021 involving approximately 38 cadets in two different platoons. Some of the teens arrived at the fight swinging socks with padlocks inside. Two cadets and two adults were injured, according to the report.

- A fight on Dec. 26, 2021 between a large group of male and female students required military police and ambulances. Eleven students were taken to the hospital.

- A fight in April 2022 between a half-dozen female cadets escalated into girls “flipping chairs, turning over ironing boards, grabbing irons and running out” of the barracks, according to the report. Staff again were forced to call the MPs to quell the fracas.

- A fight last September between two male cadets ended with one throwing a softball-sized rock at another, fracturing his jaw.

Other incident reports point to ongoing problems with screening applicants with serious mental health issues.

In September 2021, two teen cadets in separate instances confessed to plans to kill themselves. Both were transferred to mental health facilities. One, an 18-year-old, had “tried to kill himself a week before coming to the program (and) had a detailed plan to carry out a future attempt.” That same month, another 18-year-old cadet told staff he was hearing voices and was planning to kill himself by hanging. That cadet admitted to two suicide attempts prior to enrolling.

Meltdown at Fort Gordon

The fighting last fall among cadets began almost immediately when they arrived at Fort Gordon from the orientation on Oct. 10, a Monday, according to interviews with students and parents. By that Thursday, the violence had escalated into the full-scale riot.

According to interviews and records, dozens of boys from two platoons were drilling on a parade ground when members of one group began taunting the others. Even in the short week, some boys in the platoons had developed an animosity for each other based on rival gang affiliations.

Tristan Hill, Donaldson’s son, told his mother he had been in the latrine and emerged to find himself in the middle of a brawl.

“Somebody came up and drilled him on the side of the head,” Donaldson said. “Some other kids – a bigger kid – came and helped him up and helped him fight off two other kids.”

Ahsyria Pettis, a 17-year-old from Atlanta, was walking with other female cadets when the violence broke out. Their drill sergeant told them to run to their barracks.

“Boys started dropping to the ground,” Pettis said. She said she and other girls could hear the frantic chatter on the radios of the drill sergeant. One sergeant returned to the barracks hurt, having been sprayed with what she thought was tear gas, she said.

The next day, another massive fight occurred. According to the report, 25 students rushed a barracks where seven other students were being there for safety reasons “due to gang-related issues.”

“Boys started dropping to the ground."

Again, the MPs were called, but even they were unable to restore peace. According to the report, police found “numerous shanks” and socks with padlocks.

The continued disorder attracted the attention of the U.S. Army command at the base, and the acting garrison commander ordered the camp shut down and issued a blanket order barring every cadet from Fort Gordon for a year, regardless of their involvement on the program, “for the safety of the installation,” the report states.

Program administrators were told they had 24 hours to get all of the teens off base.

‘They failed us’

Parents interviewed by the AJC said recruiters and administrators promised their kids would receive counseling, mentoring and job skills in a safe setting. They were not told some cadets had violent behavioral problems, past legal troubles, and gang affiliations.

“My son just wanted to get his GED and be done with school. He’s not a problem child,” said Richmond Hill resident Vicki Hooks, whose son attended the camp. “Now I have a child who I’m worried about having PTSD from witnessing (violence).”

Brinsina Copeland, the Clayton County mom, said her son, Devonte, suffered bruised ribs as well as cuts on his back and arms. Devonte said he ended up in the middle of the melee when he tried to help a kid getting jumped by a group of cadets. Days after returning home, he was waking up at night, shaking with nightmares. Copeland said her son’s dreams of a military career were shattered at Fort Gordon.

“These kids went through a traumatic experience, a real traumatic experience,” Copeland said.

Asia Pettis, Ahsyria’s mother, said her daughter has had panic attacks since returning.

“My child wasn’t bad. She wasn’t fighting or doing anything,” she said.

Asia Pettis said her daughter was hoping to complete her education and get a leg up on a career in the military.

“They failed us,” she said. “They are not telling us the truth.”

In internal interviews conducted after the shutdown, staff, many of them retired from the military, described the program as “chaotic” and dangerous.

“Contraband checks not effective, kids hid knives in the bedding,” one cadre said.

“After kids put a hit out on me, I should have been told to go home,” another complained.

The National Guard insists that the program is not an alternative punishment for kids who break the law.

“The YCA is a voluntary program and does not accept cadets from detention centers or the court system,” Georgia National Guard spokeswoman Lt. Col. Pamela Stauffer said in an emailed statement to the AJC.

However, Several teens interviewed by the AJC said some of their fellow cadets were in trouble with the law and “flashed gang signs” to taunt their rivals in other platoons. Students said that cadets told them they were given the option to enroll in the program or enter the juvenile justice system.

‘Place the blame where it belongs’

As parents and the media began asking questions in the days after the brawls, state officials circled their wagons, providing few answers or details.

A few days after the shutdown, the guard released a statement acknowledging “a series of escalating incidents” that led to the cancellation but did not mention the riot or the injuries to students and staff.

Internal documents show guard leadership were interested in making sure the blame landed on the students.

Deputy Adjutant Ferrero in one internal email, suggested that the statement include that the cancellation was “due to the amount and degree of misbehavior on the part of a number of cadets.”

“Places the blame where it belongs,” State Director Steinbrecher replied.

The exchange made no mention of the program’s failures to screen children properly before the camp. There also was no mention of staffing shortages or other problems identified in a draft of the after-action review obtained by the AJC.

Except for the statement, the guard’s posture on the matter was one of silence.

An Augusta television reporter working on a story in late October about the shutdown asked the National Guard for an interview, state records show.

The National Guard declined the interview, but kept. Gov. Brian Kemp’s office in the loop.

“Requesting your feedback,” Lt. Col. Stauffer, the guard’s spokeswoman, wrote in an Oct. 24 email to Andrew Isenhour, spokesman for Kemp. “We do not intend to interview at this time.”

The state’s lack of transparency extended to other media outlets. National Guard officials would not accept telephone calls from AJC reporters and responded to requests for interviews with Carden with a shifting series of statements. Kemp’s office didn’t respond to the AJC’s requests for an interview.

Most of the guard’s public statements emphasized the high-risk students enrolled in the academy.

“The YCA is dedicated to help our troubled youth and we cannot run an ‘at-risk’ youth program at zero risk. We do not have the infrastructure, staffing, or training to run something along the lines of a regional youth detention center,” Lt. Col. Stauffer replied after a request by the AJC to speak to Carden.

Stauffer’s statement noted that the academy “is not a core mission of our organization,” appearing to create distance between the National Guard and the program it administers.

In addition, the statement to the AJC claimed, without evidence, that “violence in the Georgia school system has increased 200% and we are not immune from this trend.” There is no Georgia school system. School systems are local entities of counties and cities.

Six days later, Stauffer emailed that the statement should be amended to read “violence in some Georgia schools has increased 200%.” Again, the statement offered no examples and did not explain how behavior problems in a traditional school were related to violence at Fort Gordon.

A month after the shutdown, parents finally received communication from the Youth Challenge Academy —an email inviting them to apply for the class at Fort Stewart, which starts Sunday.