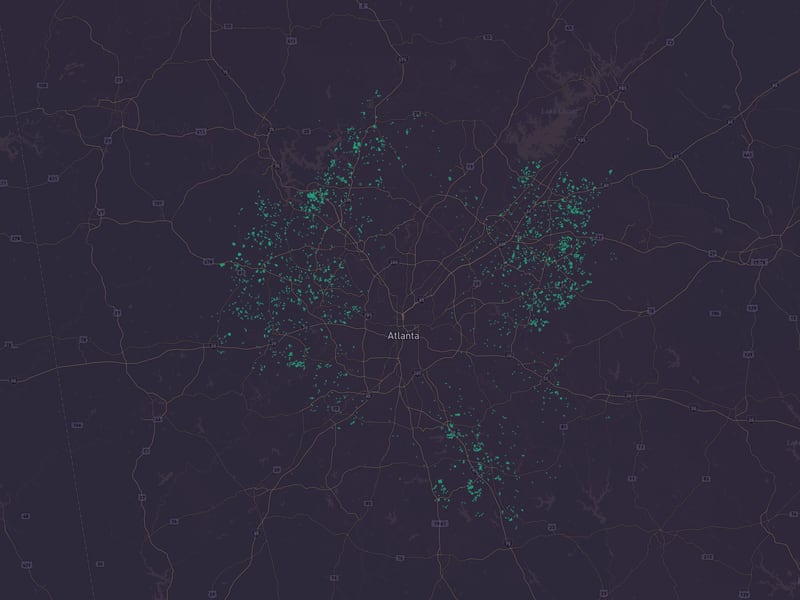

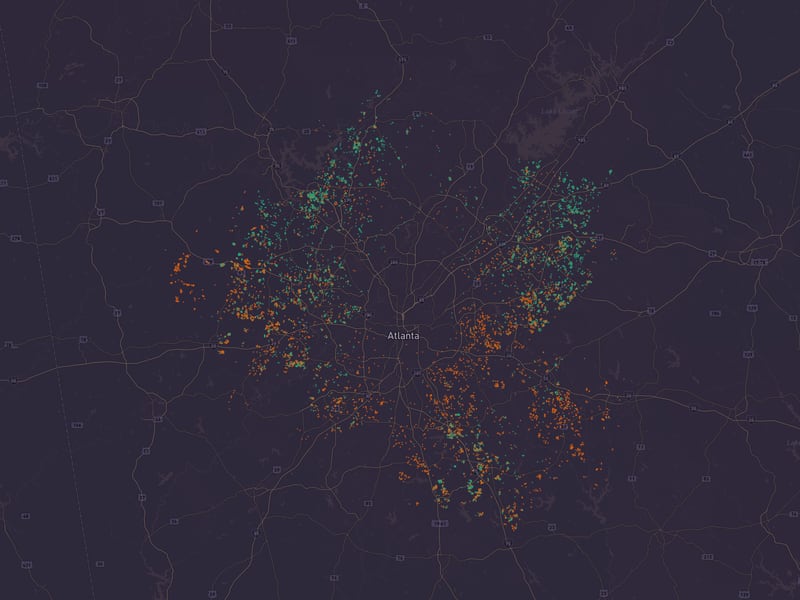

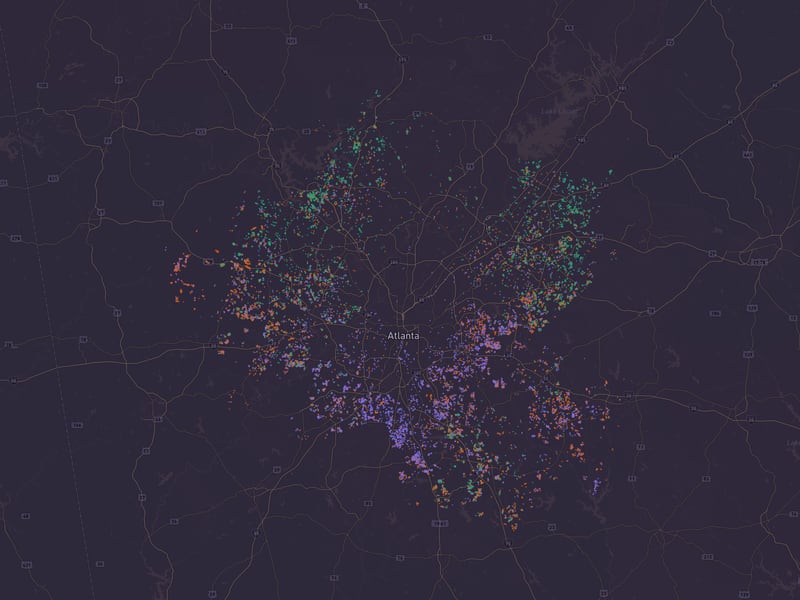

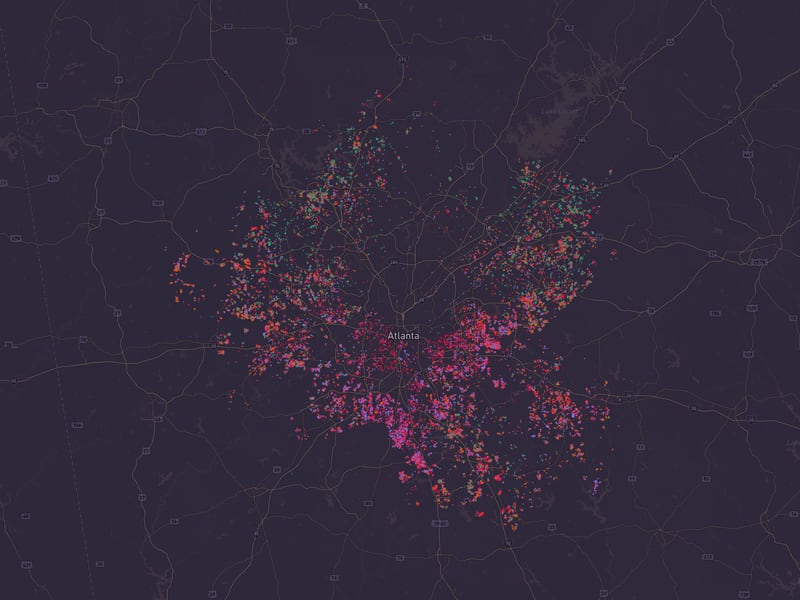

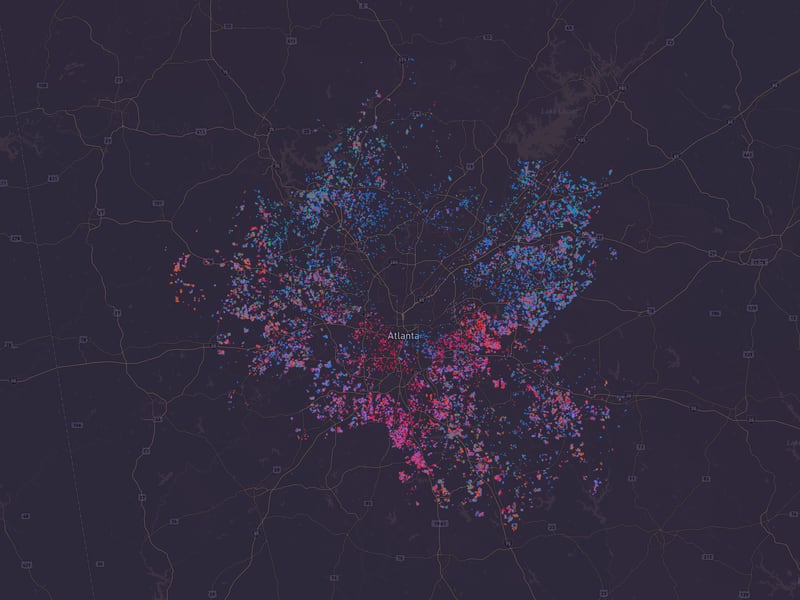

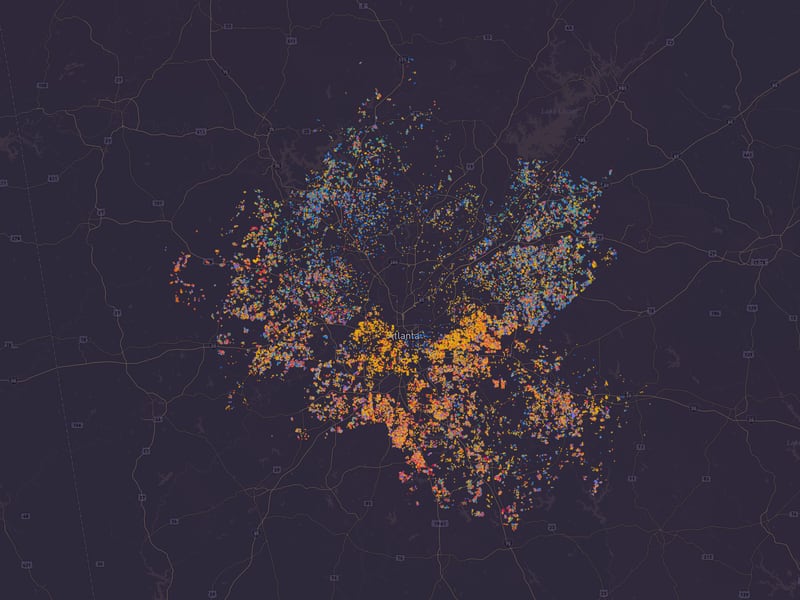

In the wake of the Great Recession, investors have scooped up thousands of single-family homes across metro Atlanta.

They compete against families for a limited supply in all but the wealthiest neighborhoods.

Instead of building wealth for residents, these homes are now a vehicle for shareholder profits.

Some investment groups own dozens of homes.

Others, like the five largest owners depicted here, bought them by the thousands.

In all, large investors own more than 65,000 homes today... and they plan to keep buying.

© Mapbox © OpenStreetMap

American Dream For Rent: Investors slam tenants with fees, evictions

Private equity makes big push into metro Atlanta’s single-family homes.

Tawana Randall’s landlord charged her a $15 penalty every month for not having renter’s insurance.

Under her lease, the insurance had to benefit not just herself, but also Progress Residential, the company that owned the four-bedroom home.

Randall said she sent proof of her policy. She emailed. She called. And month after month, the $15 fees kept hitting her account.

Finally, in August 2022, a Progress employee called Randall about the policy, she said. Not to clear up her billing dispute, but because her house went up in flames, and Progress wanted to cash the insurance check.

The growth of investor-owned, single-family rental giants like Progress Residential has come at an extraordinary cost for many of the residents who live in those homes, an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation found.

Over the last decade, investor-backed firms bought more than 65,000 houses across metro Atlanta, transforming one of the most enduring symbols of American middle class success, the single-family home, into a financial product for out-of-state and foreign shareholders.

The investor buying spree is pushing the American Dream of homeownership out of reach for many first-time buyers who find they can’t compete with the flood of cash, the AJC found.

A number of families told the AJC they were outbid by investors for a home on the one hand, only to be stuck renting from them on the other. And while the largest firms compete for houses in all but the wealthiest neighborhoods, they disproportionately target starter homes in communities of color.

Progress, Atlanta’s second largest homebuyer with more than 10,000 homes, is based in Arizona, but is owned by Pretium Partners, a New York private equity firm with over $51 billion in assets.

Armed with technological and financial advantages, Progress and other large single-family rental firms are more sophisticated than traditional landlords at scooping up homes, filling them with renters and maximizing profits. In their pursuit of higher returns, the largest firms aggressively increase the cost of housing through rent hikes and fees, while skimping on maintenance and passing many traditional landlord responsibilities on to the tenants themselves, the AJC found.

The reliance on computer automation that gives Progress a leg up in the buyer’s market can make renting from them — and a number of other similarly situated investment firms — a dystopian nightmare, renters say.

Minor problems that could be resolved with a conversation snowball into endless runarounds. Unanswered emails lead to infuriating phone calls. Two hours on hold leads to empty promises that someone in another department will call back.

“It’s like a game,” Randall said. “Why is it so hard to have a conversation?”

Over and over, Progress’ tenants described being trapped between two bad choices: Pay outrageous fees they believed were charged in error, or refuse and risk their financial credit when the company’s software locks them out of their account and triggers an eviction filing.

For this story, the AJC interviewed more than a dozen Progress Residential renters and reviewed lease documents, emails, court filings and other evidence provided by tenants. The AJC also spoke with more than a dozen housing experts, including tenant attorneys, government officials, real estate agents and academic researchers.

Progress is not alone. Experts say the company’s tactics are common among single-family landlords owned by private equity. But Progress stands out, filing more evictions than any firm in the country since the pandemic.

Progress officials declined an interview request. In a statement, a company spokesperson called eviction a “last resort outcome,” and touted the company’s partnership with the city of Atlanta to house residents displaced from Forest Cove, a troubled low-income apartment complex.

“Progress is proud to serve our residents throughout metro Atlanta, and we are committed to working with partners in the community to create access to quality single-family homes in great neighborhoods,” the statement said. “We continue to invest in talented people, tools, and technology to enhance our resident experience.”

For Randall, the $15 insurance fees paled in comparison to what came next.

An unexplained $448 utility fee from the burned-out house in Conyers she had fled a month earlier. No credit for the $1,500 balance of her August rent, after she was forced to evacuate with her two children on Aug. 12. A new $2,370 security deposit when the company relocated her. Plus, another $456 for moving in a few days before her transfer took effect Sept. 10.

Progress also kept some of Randall’s deposit from the home that burned. Randall didn’t have the carpet professionally cleaned, nor did she restore the walls “to their pre-move-in condition” as required by her lease.

After the fire, which Rockdale County inspectors blamed on faulty electrical wiring in a floodlight, the home needed much more than a routine cleaning. Randall’s ceiling collapsed, dumping black ash, insulation and dry wall all over her bedroom furniture. For the walls, Progress’ move-out instructions suggest using Mr. Clean Magic Eraser.

Rather than protecting renters like Randall, Georgia law has enabled the most egregious profit-seeking behaviors, housing and legal experts say.

The AJC found that the same power imbalance that has long allowed landlords to profit from low-income renters living in deplorable conditions is now being exploited by some of the world’s wealthiest investment groups. In doing so, they subject middle-class renters, some of whom were priced out of homeownership by these same firms, to similar treatment.

In complaints to the state Attorney General’s Office obtained through an open records request, residents said their investor landlords rented homes in hellish conditions. One woman’s laundry room ceiling collapsed due to severe mold. A pregnant woman, who has asthma, said her air conditioning was out from June 17th to July 7th. At one point during a record-setting heat wave, the temperature rose to 97 degrees inside the house.

A 2022 Congressional survey found that the average leaseholder with one of the top five single-family rental firms made an annual income of $84,852.

“The problems we’re talking about are not new, they’ve just been happening to poor people,” said Elora Raymond, an assistant professor at Georgia Tech who studies the financialization of housing. “But now as homeownership is going away for a new generation, essentially, who are we talking about? That housing stock, that price point, it’s middle-class people.

“The limelight is going on: How can we shore up homeownership, how can we make sure that the wealth gap doesn’t increase?” Raymond said. “But also could we talk about why this isn’t OK, and (why) the 35% of our society who rents shouldn’t have to live like this?”

In September, Progress locked Randall out of her account.

After spending over $2,000 on deposits and fees to move in, the online portal wouldn’t consider her rent paid without also settling up $900 in new charges that no one at the company would explain. The software tacked on late fees, then placed her in eviction status for a home to which Progress had relocated her just a few weeks earlier.

“We have the rent. We want to pay it,” Randall said. “Just get someone on the phone who will talk to me and tell me what these fees are.”

In increasingly desperate emails and phone calls over the next few weeks, Randall pleaded with Progress employees for assistance. On Sept. 25, a leasing specialist seemingly came to her rescue, telling the customer service email and six other employees that Randall had “paid more than was required,” and to remove two eviction fees, which were an additional $500 a piece.

No one made the adjustment to her account. And later that fall, a final injustice appeared at Randall’s door: the eviction notice.

Credit: Hyosub.Shin@ajc.com

An Artificial Intelligence landlord

In 2012, when federal policymakers began promoting bulk sales of foreclosed homes to convert into rentals, traditional landlords scoffed at the idea. Scattered-site rental housing was simply too cumbersome to manage nationwide, said Hannah Holloway, the director of policy and research for the TechEquity Collaborative, a nonprofit focused on economic inequality.

“It was really just private equity that was like, ‘I think we can figure this out,’” Holloway said. “And the way they figured it out was through digital landlordship.”

Today, you can rent from large companies headquartered two times zones away without ever speaking to anyone, let alone meeting your property manager in person. Through online portals, renters apply for homes, submit paperwork needed for background checks, sign their lease and make payments.

Several Progress residents told the AJC they were never given an in-person walkthrough of their home. Instead, they received a code to open a lockbox and let themselves in.

Digitizing everything from rent payments to maintenance requests cuts down on management expenses. But those savings aren’t necessarily passed on to renters. And leniency is out the window.

“If you’re a second late on submitting rent, you automatically get a fine,” Holloway said. “The automation of things that usually would’ve required a conversation with your landlord … that individual relationship just doesn’t exist with these companies when it’s just you and the website algorithm.”

Seth Ninger, an entrepreneur in Woodstock, started seeing $45 charges pop up on his Progress account for violating homeowners association rules. One was for overgrown weeds that predated his tenure by two months. Another was for painting the outside of the house. That’s the landlord’s responsibility under his lease.

When bogus fees pile up, renters say it’s impossible to pay only the rent while trying to resolve the dispute.

“Any time you send Progress money, it goes to the oldest charges,” Ninger said. And then the late fees pile up. He said he called Progress at least 40 times in his tenure, often with hour-long waits.

“Everybody was like: ‘Man, that’s insane, I can’t believe that’s happening, let me get you over to the right department,’” he said.

Then the transferred call would go to voicemail.

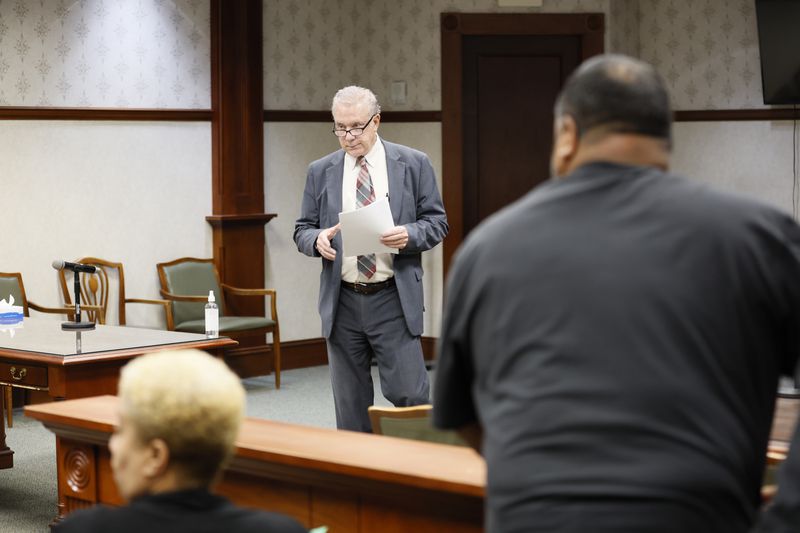

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Problems lead to eviction court

Ninger says renting from private equity has transformed the landlord-tenant relationship from a mutually beneficial business transaction to something closer to extortion.

The threat is present in every interaction: Pay up, even if the bill is wrong, or face an eviction filing.

“Eviction is cheap in Georgia. It is fast in Georgia. And it is primarily a vehicle to get tenants to pay up,” said Becky Hudock, senior policy counsel at Georgia Appleseed, a nonprofit legal policy center.

Just one out of five eviction filings results in the tenant being kicked out, she said.

“It’s just an aggressive tactic to get the money” and pile on additional fees, Hudock says. “They’re not abusing it because that is the system, and that’s exactly what it was meant to be set up for.”

While the overall eviction rate in Atlanta’s single-family housing market was 7%, Raymond and her co-authors found in a 2018 study that the nine largest investment firms filed evictions on 20% of their tenants. And corporations with more than 15 homes were 68% more likely to file evictions than mom-and-pop landlords.

Credit: Miguel Martinez

No single-family rental firm filed more evictions than Progress in 2020 and 2021, a Congressional study found. It collects three to 10 times more in late fees per tenant than three of Atlanta’s other largest single-family landlords — Invitation Homes, FirstKey Homes, and AMH, formerly known as American Homes 4 Rent. It trails only Main Street Renewal.

“Progress is committed to working directly with residents facing financial challenges to provide information and resources to support them,” a Progress spokesperson said in a statement.

Ninger got so fed up, he stopped paying the fees, went to magistrate court and reached a settlement. For others, that’s not a viable option. Even when a tenant wins in eviction court, they can lose. The mere fact that an eviction was filed can damage their credit and make it harder to find another home.

“I can’t be a realtor with an eviction notice,” said Florence Knight, a Douglasville real estate agent who is renting from Progress while she builds a home. “That’s not good for my business.”

To avoid an eviction, Knight paid Progress more than $1,000 on “HOA violation fees” in the two and a half years she has lived in her Brookmont neighborhood. But her homeowner association has never written her up for a violation, she said.

Premier Association Management, the HOA manager, sends courtesy letters to every resident reminding them to cut their grass. Progress charges a $45 fee every time a letter arrives, no matter what it says.

“They’re gonna send you a friendly reminder multiple times a month,” Knight says. “So then Progress (penalizes) you multiple times a month.”

Aside from rent and fee collection, the AJC found there’s another reason eviction filings proliferate: There’s no one at the wheel.

Ninger’s court order wiped out over $1,000 in fees. If he settled up his rent, Progress agreed, his account would be restored to good standing, and he would be eligible for a new lease in the fall.

Per the judge’s order, he took out a cashier’s check for $6,768, took a picture of the tracking number and overnighted it to the Progress headquarters in Scottsdale, Ariz. (The Progress office in Alpharetta does not accept payments or allow customers to enter the building, renters said.)

Within a month, his account was back in eviction status. Progress cashed the check, but never wiped out the fees.

Company officials declined to comment on Ninger’s case, citing ongoing litigation.

“The amount of stress that you are causing a single father with two school-aged children because of your failure to follow a court ordered agreement is unacceptable,” he wrote in an email to Progress. “The amount of anxiety and duress you are causing is unacceptable. The amount of time you are taking up is unacceptable.”

He received no reply.

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Nowhere to turn

In early December, a blue tarp billowed in the breeze on Cape Lane, loosely covering the hole where Randall’s roof used to be.

But the electrical fire didn’t stop Progress from trying to rent it to someone new. The fire-gutted home was listed on Progress’ website for $3,490 a month with a move-in date of Sept. 10, according to a screenshot Randall provided to the AJC.

The listing has since been taken down, and it’s not clear if Progress ever tried to place a new renter in the home. But Atlanta’s largest single-family landlords have a track record of moving families into places that either aren’t ready for a new tenant, or are flat out uninhabitable, the AJC found.

One family drove from Florida with young children to a Decatur rental home that was supposed to be move-in ready. They arrived late at night, exhausted, to an overwhelming stench. Atlanta-based Sylvan Homes had rented a house with no water or heat, active gas and carbon monoxide leaks, and mold, according to a lawsuit. Sylvan denies the allegations.

Knight said she submitted 13 work orders in the first week she lived in her Progress home. It took five maintenance visits to fix the leak in her kitchen sink. Progress didn’t fix the hot water in her master bathtub for 21 months, she said.

At move in, Ninger said the bedroom ceiling fan was on and the window was open in an apparent attempt to air out the smell of cat urine wafting from the master closet. He ultimately tore out the flooring and replaced it himself, and filed a claim against Progress for reimbursement. Just prior to this article’s publication, Progress reached a monetary settlement with Ninger, who signed a non-disclosure agreement.

Randall said she filed 17 work orders in the first three months after Progress relocated her.

“The automation of things that usually would've required a conversation with your landlord … that individual relationship just doesn't exist with these companies."

Local attorneys say Georgia law enables landlords to shirk maintenance responsibilities. The landlord’s duty to repair is legally separate from the tenant’s duty to pay rent.

“Many tenants are living with mold and rats and mice and flooding and leaks, and crumbling walls and ceilings and they still owe rent in full to the landlord every single month,” said Cole Thaler, an attorney at the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation. “And if the tenant makes the completely reasonable mistake of thinking that they shouldn’t have to pay rent to the landlord who is not fulfilling their legal duties, the response from the landlord almost certainly will be to file an eviction and probably win that eviction if the tenant has withheld rent.”

Tenants can turn to code enforcement when the home’s condition violates local building ordinances. But local agencies are ill-equipped to fight back against billion-dollar firms that might own hundreds of homes in a given city.

Georgia does not explicitly require that a home be habitable before a tenant moves in. And state law prohibits local government from requiring proactive inspections of rental housing. The only way to find out there’s a problem inside is for a tenant to complain. In Gwinnett County, code officers won’t go inside a single-family home even if they’re invited.

State law also bars local governments from creating a landlord registry that would give them a point of contact when problems arise. Because landlords hide behind obscure LLCs, it can take months to serve legal notice against the property manager. Repairs can drag on even longer.

Housing experts say the best approach is to force landlords to “fix it up, pay up or give it up” by placing liens on investment properties when the owner refuses to make repairs.

“It has huge ramifications for the investors,” Raymond said. “They really don’t like liens because that disrupts their ability to foreclose on their collateral.”

But few local governments have attorneys trained to do that. Instead, understaffed agencies often refer cases for criminal charges. That’s a powerful stick to use against a local landlord. But out-of-state investors ignore criminal charges and get away with it, in part because local prosecutors lack the resources to extradite suspects on an ordinance violation.

Some agencies are more effective than others. But Hudock said there are no true success stories.

“It’s just different flavors of ‘this is not working,’” she said.

When code enforcement fails, some have turned to the Georgia Attorney General’s Office. Through an open records request, the AJC obtained 39 consumer complaints against FirstKey Homes, Main Street Renewal and VineBrook Homes — three of Atlanta’s largest investor-backed buyers. Frequently, the attorney general’s complaint line advice to renters was to read the tenant-landlord handbook, hire an attorney or file a code enforcement complaint.

The AG’s office withheld an unspecified number of complaints against four of Atlanta’s six largest single-family landlords, citing ongoing investigations into Invitation Homes, American Homes 4 Rent, Tricon Residential and Progress Residential.

‘They’re all Progress.’

Experts worry that the threats to communities are beyond local governments’ ability to solve.

“You can add on legal protections here and there, but if you don’t take care of the basic fabric of a government that requires accountability in situations like this, it’s going to be very difficult to make a lot of progress,” said Michael Waller, the executive director of Georgia Appleseed.

Waller and other safe housing advocates are pushing for state legislation next year that would allow local governments to set up a landlord registry, allow tenants the right to cure overdue rent before an eviction is filed and explicitly require landlords to ensure a home is habitable before renting it out.

State Rep. Marvin Lim (D-Norcross) supports all of the above. But he believes the true solution lies with an antitrust case against investor-owned landlords. Academic research has found that in concentrated markets like Atlanta, the largest firms act similar to a monopoly, raising rent faster in neighborhoods where they have less competition.

“The state can do a lot. The county can do a lot,” Lim said. However, “this is a federal issue at the end of the day.”

After her first two years renting from Progress, Randall was ready for a home of her own. In 2020, she got pre-approved for a loan, put in an offer and lost to a cash bidder when she and her boyfriend couldn’t afford to put $10,000 more in the pot.

“The state can do a lot. The county can do a lot. ... This is a federal issue at the end of the day."

Randall lost furniture, clothes and the laptops for both her jobs. She dipped into savings and moved her two children and dog Rusty into a hotel while she waited for the insurance check to arrive.

The policy paid out $15,000 on $28,000 in damages, but “$15,000 goes really fast when you’re buying stuff that you already had,” she said. “We still don’t have clothes, we still don’t have the essentials. That money’s gone.”

Today, Randall’s trying to keep things as normal as possible for her son while he finishes high school. She started working at Target before the holidays to bring in a little extra money.

Around Christmas, Progress offered her a monetary settlement, dropped her eviction filing and she moved out.

But finding another place to live in her son’s school district was no easy task.

“How? How?” she said in early December, laughing bitterly. “They’re all Progress. You call the number and you’re with Progress. … You look on Trulia, Apartments.com and all these places, and all you see is Progress.”