Hurricane season ends with the third-most named storms on record

If you thought hurricane season ended weeks ago, you may be forgiven. The Atlantic basin produced only one named storm since late September.

But it wasn’t always so calm.

Despite the uneventful end to the season this week, 2021 will still go down in the record books. It ranked as the third-most active season on record in terms of named storms, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

All 21 storm names were exhausted, which also happened in 2020. NOAA says it marks the first time that all names were used in consecutive years.

“Climate factors, which include La Niña, above-normal sea surface temperatures earlier in the season, and above-average West African Monsoon rainfall were the primary contributors for this above-average hurricane season,” said Matthew Rosencrans, lead seasonal hurricane forecaster at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center in a news release.

The season started off early with a flurry of activity. The first named storm of the season — Ana — formed in late May. It was the seventh consecutive year that a named storm formed before the official start of hurricane season on June 1.

Seven of the storms grew into hurricanes and four of those reached major hurricane status, with winds of 111 mph or greater. A major scientific assessment released earlier this year by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that if humans continue to accelerate global warming by emitting greenhouse gases, it is likely that more storms will reach major hurricane status.

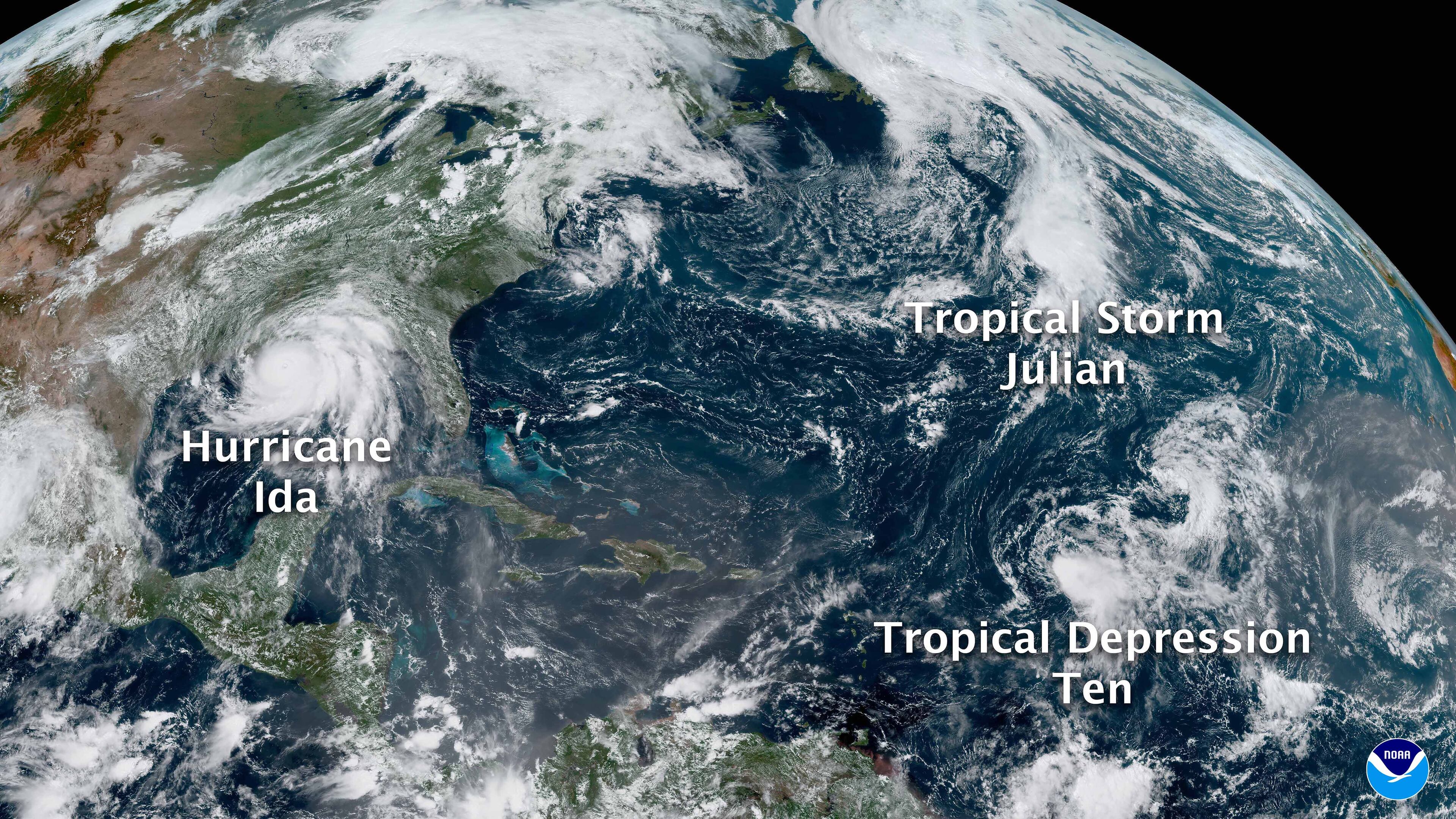

The most damaging storm to strike the United States was Hurricane Ida, which made landfall on August 29 as a Category 4 with winds of 150 mph. After hammering the Louisiana coast, the storm continued its devastating slog up the eastern seaboard, flooding towns and cities from Virginia to New York.

NOAA estimates the storm killed nearly 100 people and caused almost $65 billion in damages — a tragic reminder that the dangers posed by tropical storms extend far beyond the coast, according to Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University.

While Georgia took only a glancing blow from Ida, it was less fortunate with tropical storms Fred and Elsa, which spun up tornadoes and left thousands in the state without power.

But after a busy August and September, tropical storm activity mostly fizzled later in the season, to the surprise of some researchers, such as Klotzbach.

A strong La Niña pattern like the one that developed this fall typically favors an active late hurricane season, Klotzbach said. But that was not the case this year — largely owing to unexpected shifts in wind speed and direction called wind shear, which prevented storms from strengthening.

“La Nina tends to reduce vertical wind shear in the Caribbean,” he said. “Most strong hurricanes in the late season form in the Caribbean (as we saw last year). This year, however, we had stronger than normal shear in the Caribbean in October-November.”

NOAA will release its official forecast for the 2022 hurricane season next May.