He was arguably the most elusive suspect in the history of American criminal justice who tested the stamina of the FBI in one of the longest and expensive manhunts ever known.

The prolific assailant known as the Unabomber outwitted authorities for nearly two decades before his arrest.

Between 1978 and 1995, the meticulous serial bomber sent dozens of untraceable packages through the U.S. mail that ultimately left three people dead and 28 injured.

The perpetrator stayed out of sight until 1987, when a witness in Salt Lake City saw a suspicious man planting one of the crude homemade devices in the parking lot of a computer store. The bomb exploded after the person picked it up, causing severe shrapnel wounds.

The victim survived, and for the first time gave the FBI a clue that had remained a mystery for the first nine years of the investigation — a description of the shadowy suspect, which led to a composite sketch that has since become the most indelible relic to emerge out of the case.

The spookish drawing by renowned forensic artist Jeanne Boylan showed a mustachioed man with curly hair, wearing a hooded sweatshirt and aviator sunglasses. It was the only tangible lead authorities ever had since the first bomb was planted at the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1978. In that incident, the Unabomber had targeted an engineering professor who found the package suspicious because the box was marked with his return address but he knew that he never sent it.

Credit: File Photo

Credit: File Photo

Nine years later, the sighting of the bombing suspect in Utah seemed to be a crucial turning point in the investigation as the sketch was distributed across the country and emblazoned on the cover of magazines. But it would take federal authorities eight more years to learn the Unabomber’s true identity.

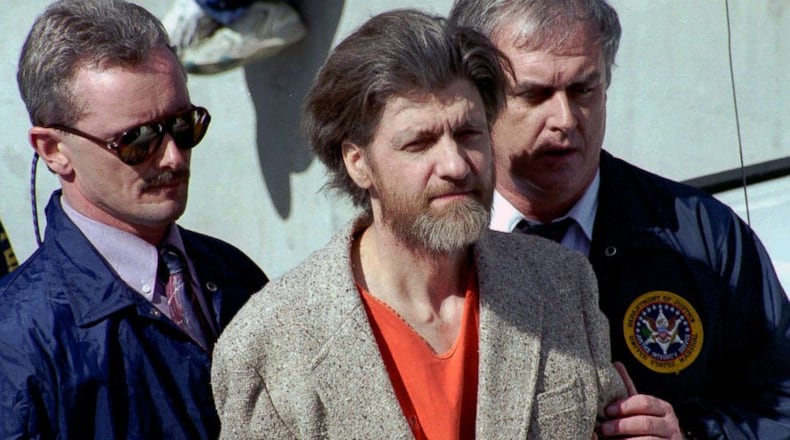

Theodore “Ted” Kaczynski, a Harvard-educated mathematician, was tracked down to a remote cabin in the woods of Lincoln, Montana, where he was finally taken into custody on April 3, 1996 — 25 years ago.

By the time of his arrest, the once clean-cut assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had grown into an eccentric 54-year-old hermit — alone, aloof, paranoid and disheveled.

His 17-year reign of terror was finally over.

Kaczynski killed and maimed professors, scientists and business leaders whom he felt were directly responsible for the decline of modern society through their promotion of technology and industrial development.

After a promising start as one of the youngest mathematics professors in 1967, Kaczynski became uneasy with his academic career and resigned from Berkeley without explanation after only two years on the staff, according to reports.

He was 27 years old.

In 1969, Kaczynski moved in with his parents for a short time and by 1971 had moved into the obscure Montana cabin where he would ultimately be caught. He purposely constructed the shanty with no electricity or indoor plumbing — human advances that he had come to detest.

Reports said he rode a bicycle, worked odd jobs around town and volunteered at a local library, where he read voraciously to occupy his time. He ate by hunting small game and picking berries from the wilderness around his isolated dwelling.

Credit: File Photo / AP

Credit: File Photo / AP

Around 1975, Kaczynski — now in his 30s — began carrying out acts of sabotage including arson and booby trapping against developments near his cabin, The New York Times reported.

By 1978, he upped the stakes and began mailing and hand-delivering bombs to random victims.

The Unabomber’s first device blew up at the Chicago university in 1978, which injured a campus police officer, according to the FBI. A second bomb, concealed inside a cigar box, was sent nearly one year later to Northwestern University but caused only minor injuries to a graduate student.

Also in 1979, another bomb was discovered in the cargo hold of an American Airlines flight from Chicago to Washington, D.C., which failed to explode but released smoke that prompted an emergency landing.

The FBI connected all three bombing incidents and gave the suspect the moniker “Unabomber” because two universities and an airline had been targeted.

And the attacks continued. Kaczynski was smart and patient, spreading out the time between bombings over months and sometimes years to throw off investigators. He also would use red herrings, such as scribbling irrelevant letters and initials on bomb parts.

Credit: U.S. Marshals

Credit: U.S. Marshals

His bombs grew more sophisticated through the years and impressed authorities.

The materials Kaczynski used left no paper trail as he purchased nothing and made everything from hand with ordinary materials.

His bombs were “intricate, tripwire-type” devices built out of wood instead of metal pipes. It was also later discovered that Kaczynski wore gloves and even vacuumed the compartments of the bombs, which allowed for no traces of DNA, hairs or fibers.

Credit: U.S. Marshals

Credit: U.S. Marshals

The bombs never exploded while being delivered through the mail but would detonate only as the package was opened.

Through the years, 16 bombs exploded, one after another, frustrating federal authorities who remained clueless to the man’s identity and whereabouts.

His early targets included Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering at Northwestern University, who was uninjured.

Also Percy Wood, the president of United Airlines, who was wounded but survived one of the bombings in 1980.

Two years later, Janet Smith, a secretary at Vanderbilt University, sustained shrapnel wounds and burns to her face, but she survived.

The next victim was an engineering professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who suffered burns and wounds.

Three years later, in May 1985, a University of California, Berkeley graduate student lost four fingers.

Six months after that, a bomb injured a psychology professor and research assistant at the University of Michigan.

Then in December 1985, Hugh Scrutton, a computer store owner in Sacramento, California, became the first victim who was killed.

Two years later came the bombing in Utah where the Unabomber was first sighted and the composite sketch made.

Credit: File Photo

Credit: File Photo

More than six years would pass before the bomber struck again.

In 1993, Kaczynski mailed a bomb to the home of Charles Epstein, who lost several fingers when he opened the package. Later the same year, David Gelernter, a computer science professor at Yale, lost the use of his right hand, and suffered severe burns and shrapnel wounds but survived.

Thomas Mosser, an advertising executive, was killed in an explosion at his home in North Caldwell, New Jersey in 1994. Kaczynski later told investigators that he wanted to kill Mosser due to his work to repair the public image of Exxon after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989.

The final bombing came in April 1995, when Gilbert Brent Murray, a timber industry lobbyist, was killed by a mail bomb addressed to previous president William Dennison, who had retired.

Throughout the 1990s, Merrick Garland, the current U.S. attorney general under President Joe Biden, oversaw the investigation as the principal associate deputy attorney general in the Clinton administration. At the time, his role in the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice coincided with other high-profile cases including the Oklahoma City bombing and the bombing at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996.

The iconic sketch of the Unabomber ultimately proved inconsequential in his capture, and in 1995 Kaczynski made a critical mistake.

After years of reclusive silence, he began mailing his political writings to newspapers, including a 35,000-word manifesto called “Industrial Society and Its Future,” which was published in The Washington Post and The New York Times.

Kaczynski’s estranged brother, David, saw the essay in the newspaper and immediately recognized the extreme viewpoints, which reminded him of letters Ted had written years earlier. Eventually, David Kaczynski took these personal letters to authorities, and linguistic experts made a positive match.

On April 3, 1996, dozens of FBI agents descended on Ted Kaczynski’s remote Montana cabin, where they found a live bomb and a “wealth of bomb components” as well as the original manifesto manuscript, plus “40,000 handwritten journal pages that included bomb-making experiments and descriptions of Unabomber crimes.”

The manifesto “was his undoing,” said former FBI agent and ABC News contributor Steve Gomez.

Credit: File Photo / AP

Credit: File Photo / AP

The trial judge refused several attempts by the former professor to fire his legal team and represent himself, and Kaczynski pleaded guilty in January 1998. He was sentenced to four life sentences at the “Supermax” federal prison in Florence, Colorado, where he remains.

In 2011, the FBI launched a probe into whether Kaczynski had been responsible for lacing several bottles of Tylenol with cyanide in 1982, another shocking whodunit from the same time period of his bombing spree. Kaczynski revealed the investigation in a court filing, saying the FBI “wanted a sample of my DNA to compare with some partial DNA profiles connected with a 1982 event in which someone put potassium cyanide in Tylenol,” Kaczynski wrote. “The officers said the FBI was prepared to get a court order to compel me to provide the DNA sample but wanted to know whether I would provide the sample voluntarily.”

Kaczynski’s DNA, however, did not match and the killings of seven people who swallowed the poisoned medicine in the Chicago area remains unsolved.

Kaczynski will turn 79 years old on May 22. He remains a prolific writer of essays and books, and regularly corresponds with hundreds of people who equate his ideas to historic philosophers including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Paine and Karl Marx, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

In May 2011, the U.S. Marshals Service opened an online auction for several of the items seized in the Unabomber case. In all, collectors paid more than $200,000 for 58 items seized during the raid of Kaczynski’s remote Montana cabin in 1996, with all proceeds going to victims and their families.

Credit: (AP Photo)

Credit: (AP Photo)

The items included a typewriter; a hooded sweatshirt and sunglasses that resemble those the Unabomber wore in a well-known police sketch; Kaczynski’s academic transcripts and diplomas from Harvard and the University of Michigan; photographs; tools that he used to make bombs; several quivers of arrows; handwritten codes; books; watches; and more than 20,000 pages of writings, including early handwritten and typewritten versions of his manifesto.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured