Historic Stockbridge cafe getting new life to help keep the past alive

For more than five decades, Carrie Mae Hambrick and her tiny Green Front Cafe was an institution in Stockbridge.

From 1949 to 2002 when she retired, it was the place where the Henry County city’s black community went to catch up with old friends from school when they came back to town after moving away.

It was the gathering spot for kids whose parents didn’t have the means for trips out of Henry County. From the cafe they could go on bus trips to skating rinks in nearby Clayton County, baseball games in Atlanta or to Six Flags Over Georgia.

And it was a must stop for those looking for a hot dog, hamburger or Hambrick’s celebrated cornbread.

“Anybody who was sick got a home-cooked meal twice day,” Brenda Shaw, Hambrick’s daughter, said of the Green Front. “You could also get clothes because people brought them to my mother for people who needed help. She also sponsored baseball teams out of her pocket so the kids would have something to do and keep them out of trouble.

“My son asked me once, ‘Why does grandma give so much away? I told him that’s just her,’ ” Shaw said

Hambrick died in 2010 at age 90, but a new owner is hoping to revive the Cafe and its role as a core of Stockbridge, which will celebrate its centennial next year. Diane Miller is renovating the one-floor cottage — which in the early years also housed Hambrick's family in the back — into a restaurant and tourist attraction for visitors who want to learn about Henry County's past, especially as the once rural community has exploded into metro Atlanta's second-fastest growing community.

Back when Hambrick opened the restaurant in the late 1940s, Henry's population was only about 11,000 people. Today about 235,000 call the county home, 5,800 of whom were added to the south metro community between April 2017 and April 2018 alone, according to the Atlanta Regional Commission.

“It should be a beacon again,” Miller said recently during a tour of the renovations to the building, which include restoring its hardwood floor, exposing the beams in the ceiling to give the restaurant a more open feel and using reclaimed barn wood to stabilize the structure’s rafters. “This needs to be a place to create memories.”

Historic heartbeat

Stockbridge officials are incorporating the Green Front into the city’s expanding historic trail. Once centered around Main Street, the trail branches out from downtown into neighborhoods along a walking path in the name of Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., Stockbridge’s most famous son and the father of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The neighborhood around Green Front includes Floyd Chapter Baptist Church, where "Daddy King" first preached at the age of 15, a field that was once home to a Rosenwald School for African Americans and a black cemetery that city leaders think contains the graves of enslaved African Americans before the Civil War.

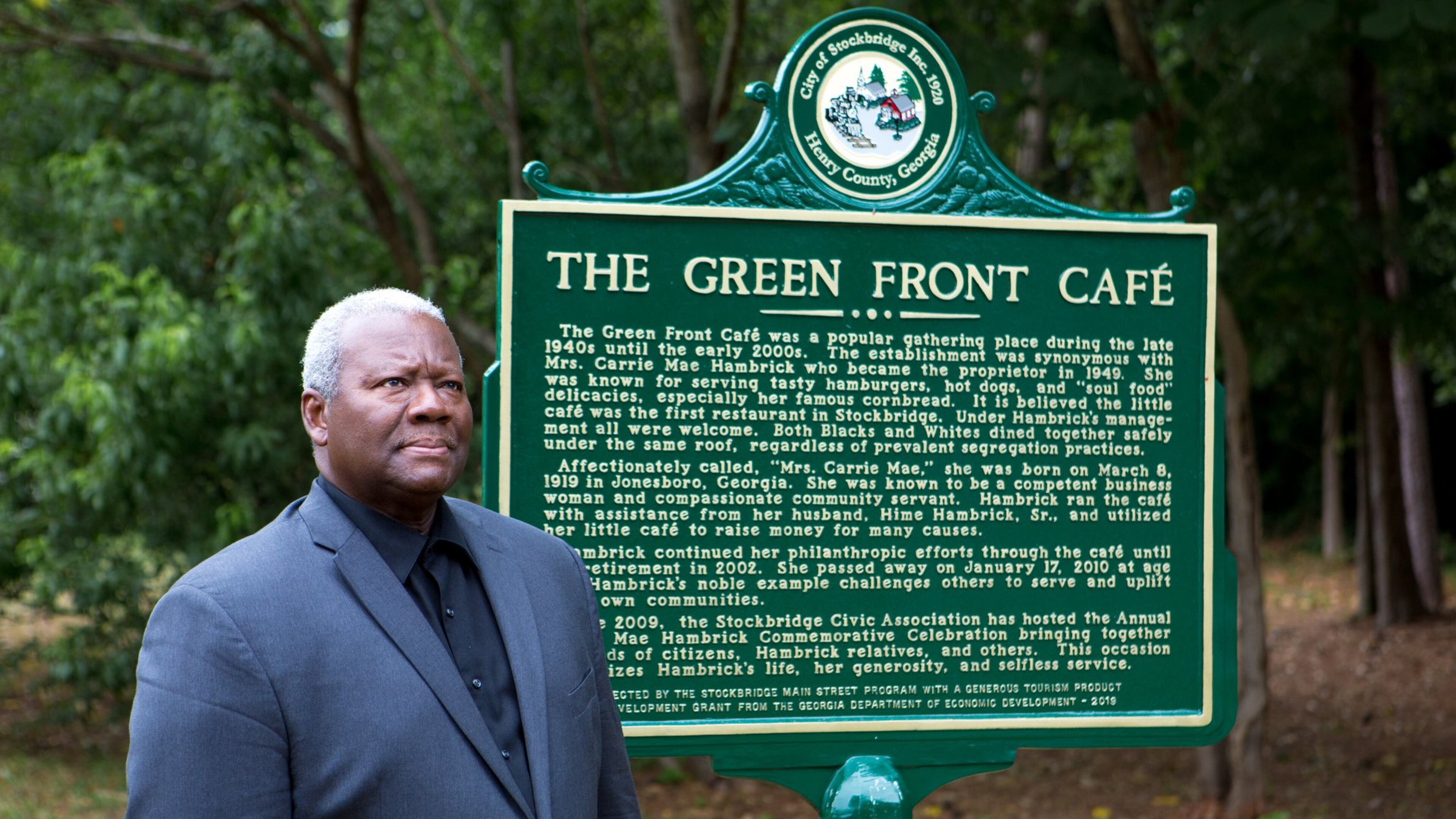

The city recently installed a historical marker at the Green Front as well as banners on light poles that include a photo of the restaurant. It also honors Hambrick every May with a community celebration and commemorative service, now in its 11th year.

“Green Front can be seen as almost a way station for the trail system,” said Kira Harris-Braggs, manager of Stockbridge Main Street. “We see this as a catalytic-type building.”

And one that will adhere to its past as much as possible while meeting modern needs and code guidelines, Miller said. There are two bathrooms instead of one and the original kitchen has been removed for one that meets today’s codes. The building will have an automated filtration systems, solar panels and Wi-Fi.

“I’m committed to this being as green as possible,” Miller said.

The community picked the shade of green used on the exterior (there were about 15 shades when work crews peeled back the building to its original surface), but not after one resident burst into tears when she saw it covered in white. It was actually the primer, but the resident thought Miller had committed sacrilege when she saw the base coat.

“This is how important this place is to the neighborhood,” she said.

Community mom

Carrie Mae Hambrick bought the Green Front Cafe from a cousin who was moving to New York and almost immediately it became a community gathering place, her daughter Brenda Shaw said. Others said it took off so quickly because the closest restaurant was in Morrow in Clayton County.

That allowed the restaurant, which was just a handful of bar stools, a counter and a smattering of tables, to integrate long before it was possible in the Jim Crow south of the 1950s and early 60s, friends and relatives of Hambrick said. Black and white Henry residents ate, laughed and caught up on the local news shoulder to shoulder at the Cafe.

“We didn’t know anything about segregation because of that,” Shaw said. “All people were invited to the cafe.”

Hot dogs at the Green Front were 10 cents and hamburgers cost 25 cents, said Stockbridge City Councilman Alphonso Thomas, who worked as a manager at the restaurant for many years and was for a period a would-be successor but could not fully take the reins because he lived in Decatur. Hambrick put breadcrumbs in her hamburgers to give them that extra oomph and her cornbread was legendary, though the recipe remains a mystery.

But equally as important was her philanthropy, friends and relatives said. She would help residents with homeowner’s insurance and had fish fries and other fundraisers if a family could not afford burial costs. Insurance agents would often stop by the restaurant to pick up payments because so many in the community left them in her care.

“She used the Green Front as her community front,” Thomas said. “She was engaged in the community in all facets.”

Most believe her commitment came from her Christian upbringing. She believed Christians were tasked with the duty of helping others when able, Thomas said.

Shaw said occasionally she will run into someone who will tell her of how her mother’s verbal or monetary intervention changed their lives, including a man who Hambrick talked out of a fight that could have landed him in jail. At least one person who borrowed money from her mother for a car kept making payments to the family after Hambrick’s death because she felt it important to keep her promise to the restaurateur.

“Sometimes I think she left us out to help others,” Shaw said.

The family sold the cafe to Miller because, after years of helping their mother from the time they could walk, they were ready to move on, Shaw said. Miller said she hopes to have the operation up and running by the end of the year.

As she surveyed the work that has been completed and the tasks still ahead, Miller said she is happy she invested in something so special to the community.

“I’m not a restaurateur or a preservationist,” she said. “But there is something about the Green Front. The story, the people, the history. It just struck me.”