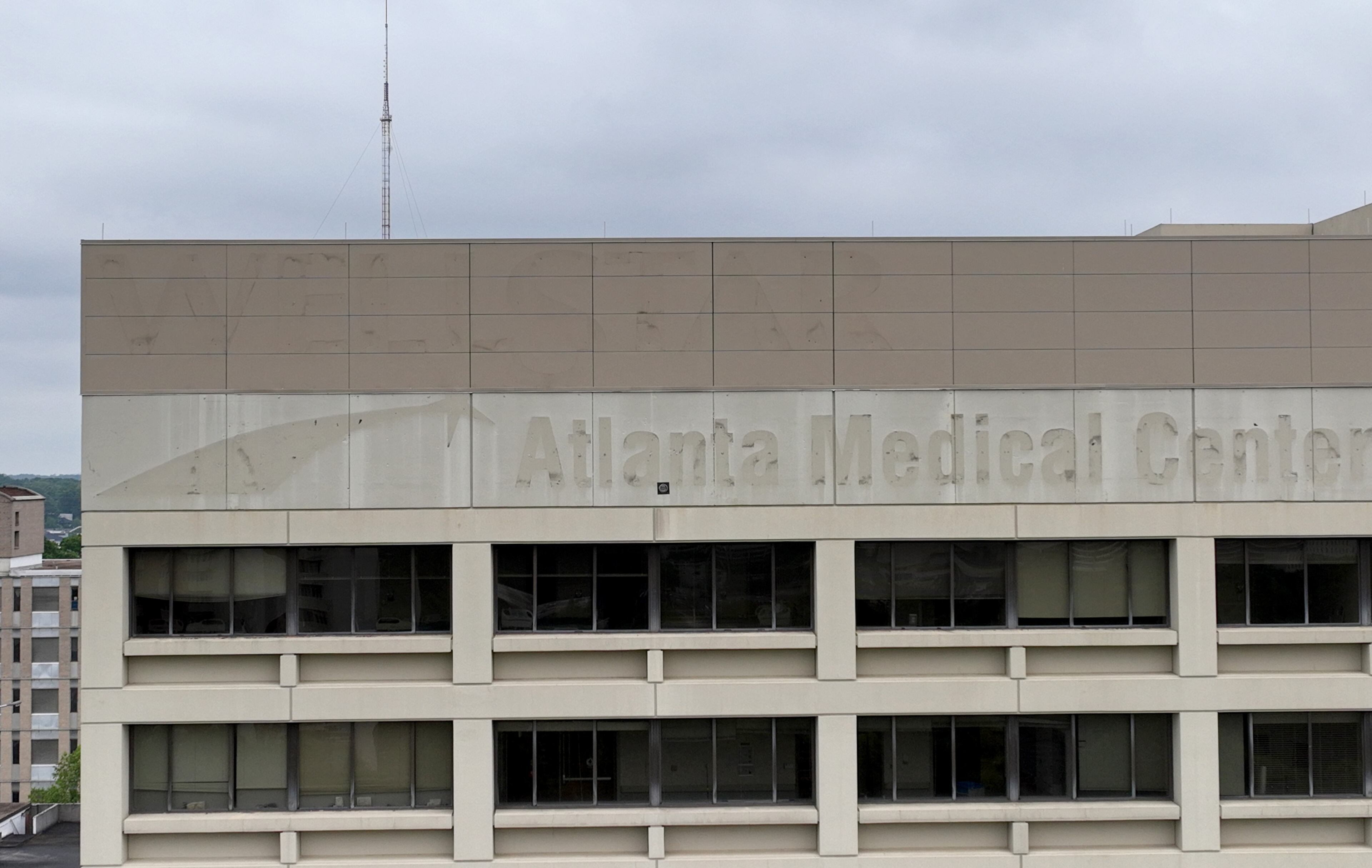

Six months after Wellstar closed two hospitals, path forward is unclear

Irene McGibbon’s pills are running out. And she knows that nothing about getting more of them will be simple.

When downtown’s Atlanta Medical Center closed about six months ago, the 75-year-old lost easy access to the doctor she’d seen for 25 years.

That doctor helped her to lose weight, checked that her medications were working and made sure they got refilled. In short, Dr. Patricia Lloyd did everything she could “to help me help myself,” McGibbon said.

But Lloyd’s office is permanently shuttered, along with AMC. McGibbon said she needs to find a new doctor to manage her medical conditions, but, without the hospital and adjacent medical suites that came with it, there are no good options nearby.

McGibbon, like many others, is keeping a close eye on what happens with the idle AMC property.

The area where AMC was located has been home to a hospital for a century. City officials would like for some type of health care facility to fill the void, possibly combined with other uses. But they are also keenly aware that the property is on the outskirts of thriving gentrification, making it potentially attractive for developers.

A city-imposed moratorium, put in place in September, bars new development at the site, which covers a city block. Now, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens is working to renew that 180-day moratorium. If the City Council agrees, it will be October — a year after the hospital’s closure — before owner Wellstar Health System can do anything new with the land.

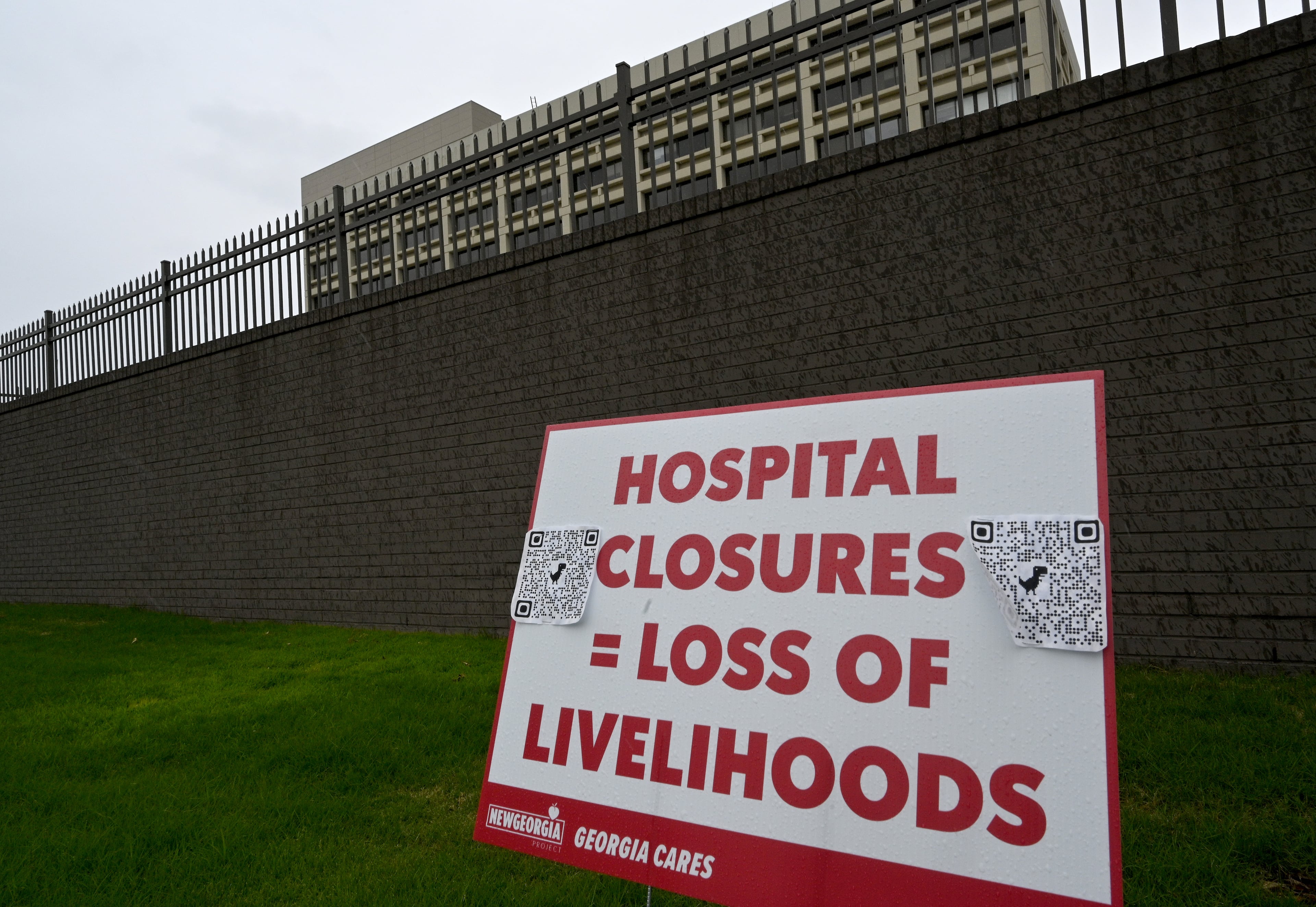

The prospect of such a large piece of property and buildings sitting dormant in the historically Black Old Fourth Ward neighborhood worries neighbors and city leaders. Many are still angry about Wellstar’s decision to close the safety net hospital and to convert a second AMC location in East Point into a clinic, citing mounting financial losses.

Atlanta councilmember Liliana Bakhtiari applauded the moratorium that blocks Wellstar, a nonprofit hospital system, from selling the land. It would be wrong for Wellstar to enter into any kind of deal with a developer after closing “two hospitals within less than a year, in some of the hardest hit areas of our city,” said Bakhtiari, whose district includes the AMC property.

Wellstar has previously pushed back against suggestions that it wants to profit off selling the AMC property, saying that assertion is “simply untrue.”

Meanwhile, in the months since Wellstar’s closures, thousands of patients have either been traveling to see new doctors or, like McGibbon, not seeing doctors at all.

Replacing the health services offered at AMC’s main campus and the hospital features of AMC South in south Fulton County will require creativity and money. And there’s little evidence of progress.

“We’re still working on trying to find the occupant for the space to make sure that we can get medical attention to the Atlanta community that needs it,” Dickens told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution last week. “And so we’re still talking to operators of hospitals, and working with the county and with some of the local providers to be able to bring about an opportunity for us to come back with something that’s a hospital there.”

Atlanta City Councilman Amir Farokhi, who represents the AMC area, said his constituents are growing impatient.

“Neither I nor residents want to see a black hole in the middle of the Old Fourth Ward for long,” Farokhi said. “The concerns I hear are, ‘Let’s move forward sooner rather than later.’”

Show them the money

In East Point, where the second AMC hospital was closed and now operates as Wellstar East Point Health Center outpatient clinic, the Fulton County Commission is in negotiations with Morehouse School of Medicine to operate a new clinic not far away.

The Morehouse clinic — intended to address concerns about easy access to primary care doctors as well as behavioral health services — would require financial support from the county. The medical college is asking Fulton to provide $4 million to $5 million in start-up costs, and later the county would need to allocate $2.5 million annually.

Fulton County already gives Grady Memorial Hospital more than $40 million in tax dollars each year, according to Grady, which on Thursday announced plans to open two clinics south of I-20. Earlier this month, the Fulton commission postponed discussions about implementing a county-wide sales tax to cover the cost of health care services.

For the former AMC location in downtown Atlanta, options proposed by council members late last year included a new health-care focused project, possibly combined with a real estate development or a city “equity center” that would provide a range of social services. But those resolutions from council members Michael Julian Bond and Mary Norwood have been tabled for now.

Fundamentally, Dickens said, the site needs to continue to provide health care, but he does not want to write a big check to Wellstar to make that happen. Bond has said that the best way for the city to get what it wants at that location is to buy the property from Wellstar, but that is likely to be expensive. “We can not hope to obtain the property by any other means,” Bond said.

Any deal that the city makes with the hospital system needs to be a “no-cost or low-cost option for us, or a provider to buy the land,” Dickens said.

Wellstar said in an emailed statement Thursday that it is considering future uses for the property, but has not taken part in any formal discussions and has no timetable for making a decision. “We expect to begin the process for determining the future use of the property shortly and we look forward to engaging with the mayor and others as that process unfolds.”

Making a new health care provider succeed there would require not just acquiring the site but paying for its operations year after year, Dickens acknowledged. He suggested the city could strike a deal with a private operator.

“It’s a really public-private partnership model,” Dickens said. “So if we could help support it, that would allow Wellstar to give it to an entity like a city or county, and then an operator will be able to be the ones that would actually run the hospital and take care of the patient needs, but we will be trying to be a part of the deal if we need to make it go through.”

Local and legislative help needed

As the city tries to settle on a new plan for the downtown AMC location, two organizations that could help provide financing and public support say they’ve not yet been brought into the discussion.

The city of Atlanta has its own economic development authority that can help raise money for such projects through borrowing, giving tax credits or using other means. Officials at the authority, Invest Atlanta, said they have not yet been contacted about helping finance anything new at the AMC site.

“The toolkit is there,” said Eloisa Klementich, president and CEO of Invest Atlanta. “We just have to understand who would be coming and what they would need.”

Atlanta Neighborhood Planning Unit M, which includes the Old Fourth Ward, also is waiting to be included in the talks.

“There’s not much engagement from the city with the local community as part of the process,” said Ross Wallace, land use committee chair for the NPU. “I think the biggest concern and request from the local community, at this stage, is to be part of the process, whatever the process looks like.”

Sen. Nan Orrock, D-Atlanta, said part of the solution for the former AMC sites should include a cash investment from Wellstar. ”Wellstar needs to step forward, be accountable and take responsibility for the fact that they really left a health care desert in the southern portion of our county,” Orrock said.

Bakhtiari, the Atlanta City Council member, said that state action is needed to fix the larger issue of access to health care. “As far as Georgia is concerned, I think the governor has a lot of work to do, and the Legislature has a lot of work to do in terms of looking at health care and making sure that people are not just barely surviving in our state but are actually thriving.”

“Something must be done because this has happened all over rural Georgia, and people are now starting to come into the city for help,” Bakhtiari continued. “And now they only have one option when they come into our city, and Grady cannot continue to carry the burden of every other health care agency.”

County Commissioner Khadijah Abdur-Rahman represents the south Fulton district. Her constituents also worry about lack of health care providers.

“We know what the problem is,” said Abdur-Rahman. “But we don’t have a blueprint for the resolve.”

Asked if Gov. Brian Kemp’s office is involved in finding a way to replace the lost hospital services, a spokesman pointed to last year’s one-time grant of federal dollars to help Grady Memorial Hospital deal with some of AMC’s former patients who were flooding through its doors, and to state dollars that are helping Grady open two new outpatient clinics south of I-20.

Left with ‘a mess’

McGibbon has lived in the Old Fourth Ward for decades, and part of what made it work was AMC and its surrounding medical office buildings. McGibbon has a thyroid disorder, congenital heart failure and vertigo. “I deal with it.” she said.

Or at least she did, when her doctor was close by.

Other residents at the seniors-only building where she lives have told her she has to make her way to a clinic at Grady Memorial Hospital. Because she doesn’t have a car, that will require McGibbon to take MARTA. She also has to find her medical records; she didn’t learn her doctor’s office was closing until its last day open.

“She explained to me I’d have to pick up my medical records by that Friday. Unfortunately I couldn’t, and now I have to go find them,” McGibbon said. “I’m not the only one.”

Experts are concerned gaps like this in the changeover to a new doctor will cause some to drop out of care altogether.

McGibbon’s former physician, Dr. Lloyd, told the AJC that she knows some of her former patients have not been able to find new doctors.

For now, McGibbon and her neighbors, friends and family rely on each other’s help to find doctors and get to those appointments. But, McGibbon said, it didn’t need to be this way.

“This is a mess,” McGibbon said. “It is so unfair.”

As for the mayor, Dickens knows restoring service there is important, he told a reporter for the AJC.

“We need it, and we’re still working on it. It’s important to our city, whether it’s there or anywhere else in the southern part of the city.”

How we got the story

The AJC has reported deeply on communities affected by the closure of Atlanta Medical Center hospitals in downtown and East Point. The AJC learned that, when the 180-day moratorium on development at the Atlanta Medical Center site in Old Fourth Ward expired on April 15, Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens intended to renew it for another 180 days. The AJC was first to report both the original news about Wellstar’s closure of AMC and of the mayor’s temporary moratorium on development there. To answer questions about what comes next, reporters contacted local and state leaders.