‘Let go’: How Atlanta artists hit peak creativity

Brain researcher John Kounios says if you want to understand what it means to be in the flow, watch a jazz performance or a video on YouTube of artist Pablo Picasso creating a painting in under five minutes.

“You can analyze anything that requires improvisation,” the Philadelphia-based researcher said. “You see evidence of flow in artistic outlets that require real-time production of creative ideas.”

That’s just what he and his colleagues at Drexel University did in a recent study that Kounios says is the first to reveal how the brain enters creative flow states. Area artists told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution that the process described in the study reminds them of their own flow states.

The flow state has been described as effortless attention to a task. It’s an enjoyable state in which intrusive thoughts and consciousness of time falls away and high concentration and original thoughts can come effortlessly.

For decades creative flow has been the focus of research and books, and it’s highly sought in pastimes and jobs requiring artistry or creativity.

Kounios learned that artists can slip into creative flow states when a part of the brain’s activity is actually suppressed. But that can usually only happen in highly trained artists. “Once you’ve done your homework and developed expertise, you essentially sit back and let it happen,” he said.

It’s a feeling that Atlanta artist, Stan Clark, said he can achieve in his studio or on an airplane. “After a 3- to 5-hour flight, I can almost always walk off the plane with a good, well-realized drawing,” he said. The act of blocking out poking elbows and pesky fellow passengers allows him to enter a flow state that leads him to “mentally decode what my mind sees into shapes that my hand renders onto the paper.”

The study called into question previous research on flow.

Researchers who look at the neuroscience of creativity had thought that flow states depended on two brain networks cooperating with each other to produce ideas, Kounios said.

“The thinking was that the brain’s “default mode network” would draw from memory to produce the stream of Ideas. The “executive control mechanism,” or the front of the brain, would then supervise those ideas,” Kounios said. He likened the default brain to a firehose spouting water, and the executive brain to the firefighter holding the spout. “We found that in highly experienced jazz musicians in a state of flow, activity in those two networks is actually suppressed. Instead, there’s this other network in the left hemisphere of the brain that seems to be taking over and producing Ideas. It had been thought, prior to our work, that the two networks were needed and worked together.”

J. Douglas Bremner, a professor of psychiatry and radiology at Emory University School of Medicine, called the research “interesting,” and said it makes sense to him as a former tennis player. “You teach yourself how to move your arm, how to move the racket. But at a certain point, the motions become automatic. And in order to be competitive, you have to stop using your conscious brain — the frontal cortex — and just let the movement take over. The conscious brain can ultimately inhibit the movement.”

Though the Drexel research is reflective of most experts’ thinking on the subject, Genevieve Cseh, a specialist in flow at the Centre for Positive Psychology at Buckinghamshire New University in Wycombe, England, says there’s more to it. Her research argues that there is, in fact, a more deliberate and effortful thought process to creativity.

“I’d say jazz improv involves different creative thinking patterns potentially than plotting and writing and editing a novel for instance,” Cseh said. “A lot of people seem to focus on the romantic part of creativity as this unconscious process of the muse talking to you, but they forget all the editing and consciously trying things out, evaluating them to see if they work or not, back and forth that happens in the creative process a lot of the time.”

For Atlanta-based pianist and composer, Madoka Oshima, the mere act of playing a piece, whether an etude or a jazz number, brings on the flow state. “Now that I’ve been playing music for a long time, it starts right away,” she said. “I follow the rhythm or harmony. It’s like kneading clay. I start to work with whatever I hear.”

Kounios says even untrained artists can find a flow pattern by slowly developing expertise and confidence in their abilities. “The way to develop the self confidence that is critical to flow is to start small,” he said. “Think of a young stand-up comedian. The comedian might practice with family. Then with friends. Then work at little, out-of-the-way comedy clubs. You have to build up self confidence any way you can in order to let go, relax your grip, and let the flow experience ensue.”

How Atlanta Artists Get In the Flow:

In Kyoung Chun, visual artist based in Atlanta

“I keep adding, I keep working when I’m in the flow. It can even occur at 3 am. I might even wake up in the middle of the night and start the flow process. It’s almost like a moment of nirvana. It’s not superficial like going to a fancy restaurant or shopping for nice clothes — it’s fundamental, it’s basic, it’s existential happiness, and it requires preparation.”

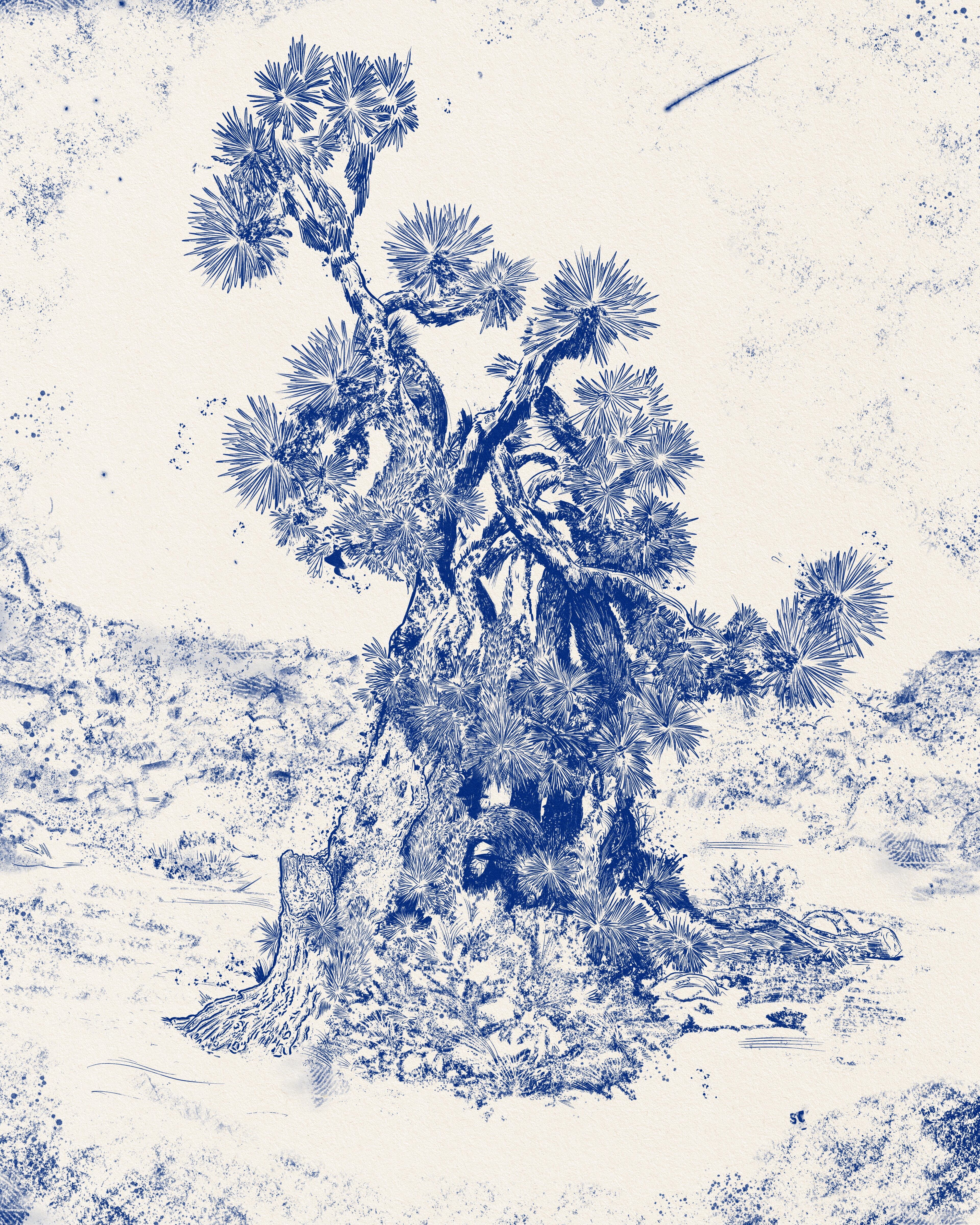

Stan Clark, visual artist based in Atlanta

“Being on an airplane is a good place to be in a flow state. My brain rebels against the boredom and tedium. Being on a plane puts me in a certain emotional place too. Waiting to catch a plane, or the stress of passing TSA, gives way to a kind of reverie once in the sky. The ‘looking down on life’ feeling from the air puts me in an emotional place as well, and that encourages the flow. It brings about a kind of quiet. Being on a train can do it too.”

Joe Gransden, jazz musician

“The flow came after years of practice. But very early on, as a young student, I had glimpses of this amazing feeling of improvising — making something up on the spot that I felt sounded good, and the musicians around me thought sounded good. With regards to the trumpet, I’m able to direct that feeling of creative flow through the horn. I will take chances, but I know my limitations — if I hear something in my head, I can judge quickly whether I can reproduce it on the horn or, if not, send myself in a different direction. You don’t really know where the brain will take you in that moment. But you will escape everydayness.”

Madoka Oshima, jazz musician and pianist

“I can be in a flow state playing almost anything — an etude or a classical piece, or a jazz piece. Playing piano itself is really something that I like doing, physically. Aside from trying to create something with the notes, just playing, the act of playing, puts me into a flow state. When I play with certain people who are really good, we can almost talk with music and enter a flow state. Music provides tension and release via the harmony, rhythm, and dissonance. When that happens, it feels exciting.”

Judy Pfaff, visual artist who works appears in the High Museum

“I’m not sure I recognize it until it’s been happening for a while, so maybe I don’t have a point of realization. I just move freely around the studio space starting and stopping different things and when I feel like I’m losing focus on something I stop and watch TV to gather myself. I built my studio in a way where I can sort of always be working, so maybe I just live in a constant state with ebbs and flows.”

Ato Ribeiro, visual artist

“I play music because it helps me establish a tempo, a flow. It’s also a timer for me. If I’m listening to a Willy Nelson album, or to Andre 3000′s jazz album, I’m hyper focused on the music, but I’m also hyper focused on the sound of the blade moving over the wood. I actually think of ‘losing one’s self’ as a form of collaborating with the musicians who inhabit the room with me, with the tools that might be in other areas of the room. If a machine makes a certain sound, I know I can pause the music. With natural materials like clay and wood, you start working through your fingers — your fingers just know how to sculpt the materials.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of In Kyoung Chun, a visual artist based in Atlanta