Atlanta struggles to reduce HIV rates

Whenever she meets a woman in Atlanta who has newly acquired HIV, activist Masonia Traylor experiences a cascade of emotions that bring her back to her own diagnosis 15 years ago.

“I cry when it happens,” she told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Women often find out while they are pregnant. It angers me. They tell me ‘I didn’t even know this was still a problem.’”

It’s all the more tragic because HIV drugs can keep people from catching the virus, and prevent those living with the virus from passing it on. If everyone who needed these drugs could access them, activists say new HIV infections in Atlanta would fall by 90%, potentially saving taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

Medicines given to those living with the virus render it untransmittable via sexual intercourse. But pills called PrEP, for pre-exposure prophylaxis, are considered the missing link to ending HIV because HIV-negative people who take them are nearly 100% protected from acquiring the virus. There’s even a new PrEP drug that researchers could soon give as a twice-yearly shot — a discovery of such importance that the drug, called Lenacapavir and produced by Gilead Sciences, Inc., was Science Magazine’s breakthrough of 2024.

But in Atlanta, gay Black men and straight Black women have been left behind, experts said. Black women are now the second-highest group of people testing positive, outpacing infections among gay white men, traditionally one of the most at-risk groups.

Activists and researchers say the reasons are twofold: a large, uninsured population in Georgia means some can’t access medical care, while stigma among Black Georgians has made HIV taboo. Until these issues are addressed, they say, the Peach State will struggle to close the gap between scientific advancement and the mundane reality of treating at-risk patients in Atlanta.

The most exciting and new dimension to Lenacapavir is that it might eventually be administered as an annual shot, much like a vaccine, and could help end HIV in Atlanta and around the U.S.

In two trials funded by Gilead, one of which took place in Africa and a second at several sites in Asia, Latin America, and the U.S., including at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, the drug was nearly 100% effective as PrEP. The test of the twice-a-year shot was so successful that Gilead quickly opened a second trial to evaluate whether Lenacapavir could be given annually.

Dr. Colleen Kelley, co-director of the Emory Center for AIDS Research and leader of the Atlanta team that looked at Lenacapavir’s effectiveness, said miracle drugs only work if people can access them.

She points to another injectable PrEP drug called Apretude made by Viiv Healthcare. It’s just as effective, and has been FDA approved since 2021, but not widely used.

“People really want to be on Apretude, but they don’t know how to get it,” she said. “Clinics had to learn how to deliver an injectable every two months. And insurance coverage remains very difficult. From a public health perspective, we have done a really poor job around access. This time around with Lenacapavir, we run that risk again.”

Moreover, government and drug companies aren’t reaching people who could benefit from PrEP, said Leisha McKinley-Beach, a national HIV consultant and CEO of the Black Public Health Academy, which prepares Black health department employees for leadership positions.

She said a free, nationwide PrEP program sent thousands of bottles of medication back to the pharmaceutical company. “This is evidence to me that cost is not the major factor but awareness, knowledge, and community connection is,” she said.

Only 25% of 1.2 million people in the U.S. who would benefit from PrEP have been prescribed it, according to a study by Harvard researchers.

Nationwide, about 1.2 million Americans are living with HIV, and 31,800 acquired the virus in 2022, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), a nonprofit that provides health policy research, polling, and journalism.

In Georgia, 2,575 people were diagnosed with HIV in 2022, and 60,902 Georgians are living with HIV, according to the Department of Public Health.

Only Miami and Memphis outrank Atlanta in terms of new HIV infections, the AJC reported.

Joshua O’Neal of the Southeast HIV/STI Prevention Training Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said PrEP injectables have been rolled out in San Francisco and Seattle, but uptake in the South has been slow, with the exception of a free PrEP program at Grady Memorial Hospital.

“Many people can’t or don’t want to take medication on a daily basis,” he said. “This is why these injectables are revolutionary.”

Most people living with HIV take daily medicine in tablet form, and many people on PrEP do the same. Both groups sometimes develop pill fatigue, said Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu of the Yale School of Medicine and principal investigator of the global Lenacapavir trials.

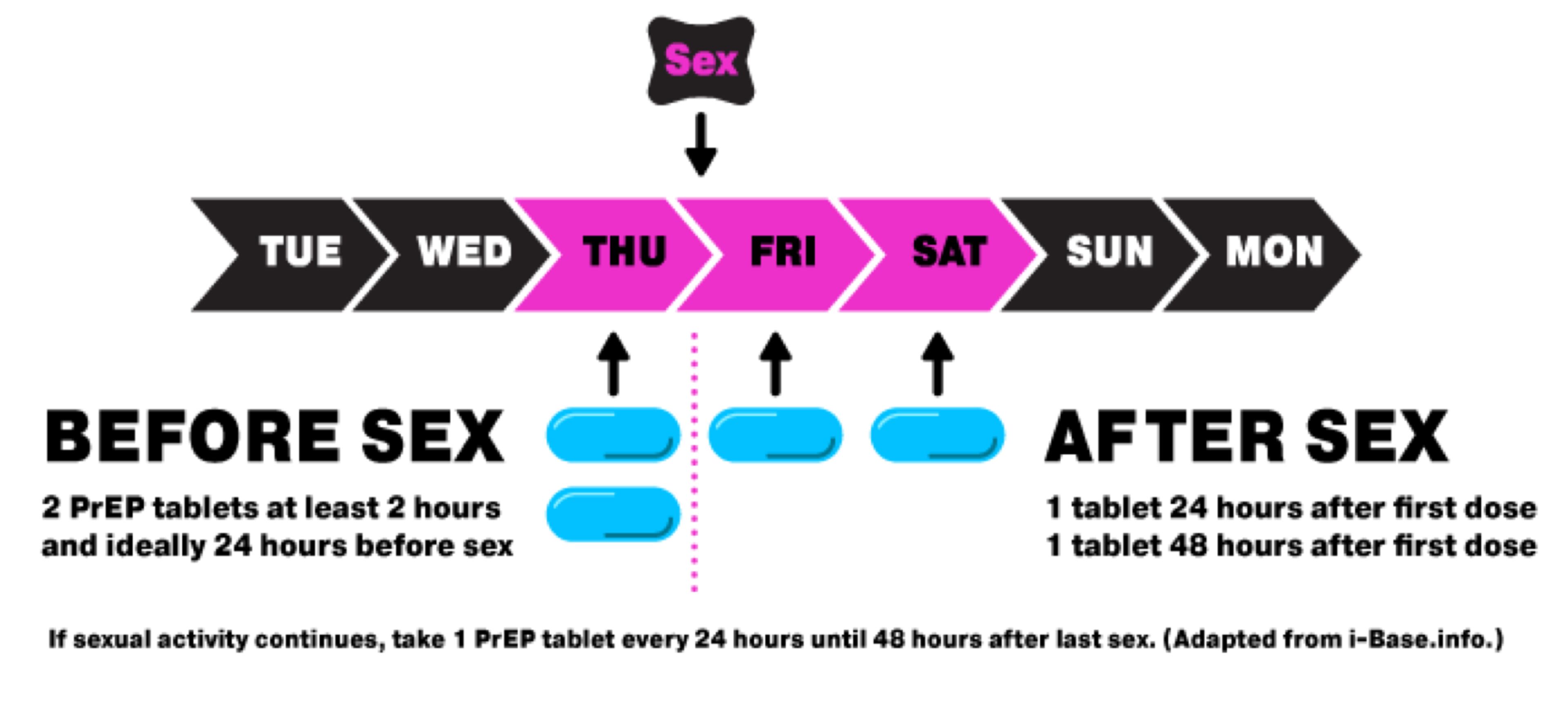

One solution to pill fatigue employed in New York City and many European countries is to prescribe PrEP “on-demand” rather than daily. Activists attribute their successes in driving down HIV infections in gay men, in part, to the flexibility that on-demand dosing allows.

If access to the drugs is the bottleneck, stigma around HIV serves as a barrier stopping Black gay men and Black women from achieving the decline in HIV infections seen in white gay men.

“The conversation in the Black community is not as accepting as in the white gay male community,” Traylor said. “I am one of two cisgender Black women talking about her diagnosis. I know thousands of women who don’t feel it’s anyone’s business.”

She said Black women worry about being fired from their jobs or losing housing if they are associated with HIV, irrespective of whether they are living with the virus or taking PrEP pills to prevent it.

Dr. Jared Baeten of Gilead said the company’s research corroborates this.

“You may not want to bring home a bottle of pills for HIV prevention that your aunt, or your partner, or boyfriend might discover,” he said. “People asked for something that was discrete.”

Randevyn Pierre of Viiv Healthcare said people are also sometimes afraid to talk to their own doctors about PrEP due to fear of judgment. “This stigma-driven disconnect is a significant barrier to PrEP access that doesn’t get enough attention,” he said.

HIV experts in the South hope that President Donald Trump will recommit to his 2019 goal to end new HIV infections in the U.S. within 10 years.

Kathie M. Hiers, CEO of AIDS Alabama, said her organization and others in the South will need help from the federal government and drug companies to be able to access injectable HIV medications.

“I love the idea of long-acting injectables,” she said. “But the reality is, we have to get whatever good medication at lower prices in the states that don’t have Medicaid expansion.”

Additionally, people experience barriers like time constraints, reliable transportation, and other logistical challenges to receiving injectable forms of PrEP from a provider or pharmacist, said Tristan Schukraft, CEO of MISTR an online PrEP pharmacy that has a program to mail free PrEP to uninsured patients.

Dr. Onyema Ogbuagu of Yale said Connecticut’s mandatory HIV testing requirement for all patients who seek treatment in emergency rooms has helped the state catch HIV infections in young people who lack insurance.

Grady Memorial Hospital has an “opt-out” HIV testing policy in its emergency room and 13 primary care clinics. But HIV testing in an emergency room setting is not otherwise mandated in Georgia, the Georgia Department of Public Health said.

Traylor says Black women living with HIV could be the best ambassadors for PrEP and treatment if society would stop judging them.

“We have to destigmatize HIV so that people who are living with HIV will actually feel comfortable talking about it,” she said.