Uncertainty, but also dedication, was the tone at a long-planned meeting of public health workers Thursday in south DeKalb County.

A few miles west, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was hosting broken links and changed pages on its website under White House orders to stop work on diversity, equity and inclusion programs. Overall, federal funding for health research was in question.

But for the nurses, counselors, public health workers and nonprofit managers at the conference, focusing on racial and economic gaps in health showed up as one of their key strategies to lowering rates of sickness and death. And a lot of such local work is funded with federal grants.

“I think uncertainty and instability would be a great way to describe the feelings that we’ve experienced over the past week, to put it lightly” said Caitlin Barringer, community partnerships manager for Open Hand. The nonprofit provides medically tailored meals, for example to people after they’ve been released from the hospital.

U.S. Sen. Jon Ossoff on Thursday morning released a statement charging the Trump administration with attacking the CDC and “endangering Georgians and all Americans who depend on the world’s leading public health agency.” He continued, “The Trump Administration’s apparent campaign to hollow out America’s public health system puts us all at risk.”

Trump’s executive order on DEI said the concept had infiltrated the federal government, leading to public waste and discrimination.

“That ends today,” he said. “Americans deserve a government committed to serving every person with equal dignity and respect and to expending precious taxpayer resources only on making America great.”

At the conference — hosted by Emory Healthcare at House of Hope Atlanta — workers traded resources, strategies and tools in their work to improve health and fight early death and sickness.

Workers described programs to connect people with primary care doctors before their health problems turn into emergencies, or to make sure people are given medication instructions they can actually read and use. They recounted bringing CPR training to an Atlanta Hawks game and using medical translators in the hospital so patients can give full answers to medical history questions and understand the instructions they’re given.

Several times they mentioned research showing that those programs were followed by improvements in health and savings of money.

Barringer said their data shows that people who get their medically appropriate meals are less likely to be readmitted to the hospital afterward. That’s not only better for the patient but represents a savings of $6,000 per patient to the health system, she said.

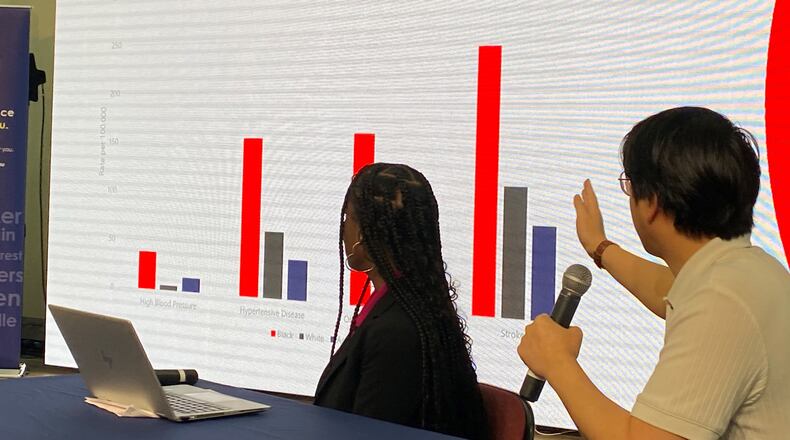

Stefani Carter, DeKalb Public Health’s community health director, openly addressed the role of diversity, equity and inclusion in improving health outcomes. She presented data showing the county’s Black residents were much more likely than white residents to die of heart attacks, cancer and external causes.

Emory’s chief transformation officer, Dr. Amaka Eneanya, gave a health equity report, but she rejected the term “DEI” and told a reporter that it was a political term. Focusing on equity, she said, allows medical science and public health to work toward giving every patient an equal shot at health.

Eneanya, a nephrologist, played a central role in the fight to remove race as a consideration in a widely used test for kidney health. Until recently, Black patients were scored as healthier just for being Black, which meant they were less likely to be placed on transplant lists and given intense care.

“All data is helpful,” she said.

Jeremy Cole, executive director of Mosaic Health Center, works to provide primary care to adults in the Clarkston area, which has a significant immigrant population. He said in an interview that there is an economic benefit of getting people healthier on an ongoing basis.

“We’re helping people get healthy,” he said. “We’re helping people be able to go back to their jobs.”

For him, he said, the mood is “determination. We’re determined to keep the focus on serving the community. People are sick and they need health care.”

Barbara Gibson, housing services director at the Women’s Resource Center to End Domestic Violence, had a similar message when she addressed the audience.

“We will not collapse,” she said. “We will be strong. We will hold each other up, and we will continue because the work that needs to be done is going to get done if we support ourselves and each other to make it happen.”

The maelstrom won’t end soon.

While the meeting was ongoing, a congressman from Rhode Island posted on social media that the federal government appeared to have shut down funding to community clinics he knew in that state.

Some community clinics that receive federal funding were participating in the DeKalb County conference. Representatives for those clinics at the conference were not aware of a funding cutoff.

Duane Kavka, director of the Georgia Primary Care Association, said last week that there were “some problems” at federally funded community clinics but things are “mostly back to normal.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured