Gordon Corsetti made an extraordinarily brave decision in 2018 when he wrote an essay for USA Lacrosse Magazine about his battle with depression and his attempts to take his own life.

“I write this to debunk the notion that no one cares, that no one understands — so that someone in a dark place can find hope in my words, and so I can finally be free of my silence,” he wrote.

“For those of you suffering alone, I do not know your pain. I know only the extent to which I have experienced mine. I felt alone. I felt as if I wasn’t worth the companionship of others. If I found help from those around me, that means you can, too. Give voice to your pain.”

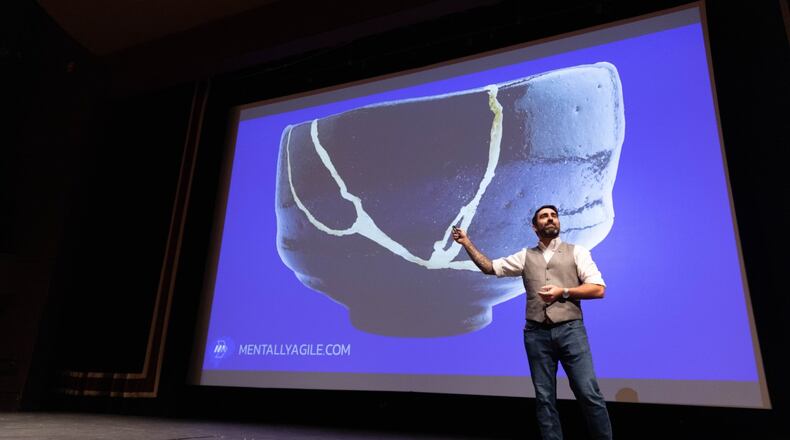

Empowered by the positive feedback he got, Gordon began speaking publicly as an advocate for suicide prevention and created a related company, Mental Agility. He published articles about his difficult experiences and talked openly about them on YouTube.

Meanwhile, Gordon threw himself into activities that helped him focus on the moment and recover, including officiating lacrosse. Invented by Native Americans, lacrosse is nicknamed the “Medicine Game” because those who play it believe it helps them heal. Gordon credited the sacred sport for saving his life.

He was resilient and fought his depression fiercely for years, underwent therapy and took medication. He had the support of many friends and his family. But all of that was not enough on Dec. 2, when Gordon died by suicide at 34.

Yet, his important work lives on today through a foundation his family created in his name for mental illness research and suicide prevention. It has already raised more than $60,000 from family, friends and strangers.

“I am blown away by it, but it doesn’t necessarily surprise me because of the reach that he had,” said his father, Lou Corsetti.

This is where I should pause and tell you that Lou was my son Casey’s first lacrosse coach. And Gordon was my friend. We played lacrosse together, officiated games together and served alongside each other on the Georgia Lacrosse Officials Association’s board. My wife, JoAnn, and I contributed money to the Gordon Corsetti Mental Agility Foundation.

I admired how Gordon had guts. My respect for him grew as I talked to some of his other friends for this article and learned new things about him. For example, Susie Reece, a fellow suicide prevention advocate, told me she and Gordon were working on a national year-long mental health education program for young people before he died.

“I know quite a few mental health speakers and suicide prevention advocates, and Gordon was just very genuine and authentic,” said Susie, director of lived experiences initiatives for the federally funded Suicide Prevention Resource Center. “He was just so good at what he did that it really was just a matter of time before he was most likely an international speaker.”

Credit: Cecil Copeland

Credit: Cecil Copeland

How to absorb a hit and fall

Born in New Jersey, Gordon moved with his parents, Lou and Mary Jo, to the Atlanta area in 1990. Lou had been a standout lacrosse attackman for Marist College’s Red Foxes. The retired business executive brought his love of the sport to Georgia and aided its substantial growth here by cofounding Atlanta Youth Lacrosse. Gordon and Mary Jo helped run it. Meanwhile, Gordon followed in his father’s footsteps and became an exceptional lacrosse athlete, first competing for Pace Academy and then Presbyterian College.

I was struck by how Gordon never did anything halfway. When he got interested in officiating lacrosse, for example, he not only became excellent at it, he wrote a book about it, “Advancement Rules: Improving Your Lacrosse Officiating.” He created his own referee training videos. In my favorite one, Gordon demonstrates how to safely absorb a hit and fall after inadvertently colliding with a player. I chuckled watching him wince as he rolled around in a field on camera. To master the game, Lou told me, Gordon typed the entire “Boys Lacrosse Rules Book” into his phone.

USA Lacrosse, the national governing body for the sport, saw Gordon’s potential and hired him in 2014 to educate and train officials. After about five years excelling on the job, he moved back to the Atlanta area and eventually became an electrical lineman, another activity that helped him focus on the moment and heal. He joked about his career switch, acknowledging how he had benefited from electroconvulsive therapy, his sister Caitlin Corsetti Luscre of Dunwoody wrote in his poignant obituary.

Gordon’s family reminisced with me about him recently at Lou and Mary Jo’s home in Roswell. Their living room was filled with bright red poinsettias brought by their friends from Fellowship Christian School in Roswell, where Lou coaches lacrosse. Caitlin underscored for me how Gordon was able to connect with his fellow electrical linemen. I learned that he repeatedly returned to his alma mater, the Elite Lineman Training Institute in Tunnel Hill, and talked to the students there about suicide, the power of vulnerability and how to be resilient.

“In Gordon’s fashion, he would sit them down and he would say, ‘Guys, I am about to make it really awkward in here,’” said Waylon Hasty, the institute’s founder and owner. “‘We are going to discuss some crap that you don’t want to discuss. But I am going to do it anyway because that is why I came.’”

Invariably, Waylon said, the students thanked Gordon for talking about those difficult subjects.

Gordon spoke to hundreds of others across the country, sharing his tips for thinking positively, meditating and using breathing exercises. In March, the Interfraternity Council and Sigma Chi at the University of Georgia invited Gordon to speak in Athens. Sam Granelli was in the audience that day. Diagnosed with depression, the UGA student said Gordon’s essay in USA Lacrosse Magazine helped him understand he wasn’t alone.

“It was really the first time I had ever heard a male around my age talking about it, even discussing that it was something that anybody could go through,” said Sam, who got to know the Corsetti family while participating in Atlanta Youth Lacrosse. “For him to talk so openly, it really helped me feel that it wasn’t just me who was going through it.”

Credit: Austen Risolvato of Carraway Weddings

Credit: Austen Risolvato of Carraway Weddings

Etowah Indian Mounds

A week before he died, I met Gordon for coffee in downtown Cartersville near his home. As we often did, we chatted about the books we were reading. Gordon was extremely intelligent and well-read. We talked about the therapy he was undergoing for his mental health. I noticed the gleam in his eyes as he excitedly told me he was planning to travel to Germany to visit his fiancée Lisa Köngeter’s family and ask her father for permission to marry her. I was thrilled for him.

When it was time for us to part, I hugged him just outside the coffee shop, told him he mattered to me and added: “We need you in this world.” That was the last time I saw him.

For years, I had wanted to visit the Etowah Indian Mounds near where I met Gordon that day, but I had never found the right time. Something compelled me to do it immediately after I saw Gordon.

I climbed to the top of the highest mound at the historic site, which some archeologists date to about A.D. 1000. The community’s chief is believed to have presided atop that mound over ceremonies in a plaza below, where fellow Native Americans played a game from which lacrosse originated. I was alone. It was peaceful and quiet up there. I felt serenity as I gazed at the surrounding countryside dotted with round hay bales. I have Gordon to thank for that moment and many other moments in my life.

Since his death, I’ve been grappling with the fact that he took his own life despite being so strong, despite being such an outspoken advocate for suicide prevention and despite having so much support from those around him. At first, I attributed it the formidability of depression. But that didn’t completely satisfy me.

John Trautwein — a former Major League Baseball relief pitcher from Sugar Hill who lost his 15-year-old son, Will, to suicide — helped me see the situation in a different way. Our mutual friend Gordon, he reminded me, survived his depression for as long as he did with the support of his friends and family and the healing that came from his advocacy.

“It breaks your heart,” said John, co-founder of the Will to Live Foundation, which fights teen suicide. “But, oh, we are so thankful for the time that we had with him.”

Credit: Jeremy Redmon

Credit: Jeremy Redmon

‘You do not have to be good’

Lisa met Gordon on a dating app, and they had their first date in August last year. They met at Cherokee Brewing and Pizza Company in Dalton, where she teaches junior high school German. His intellect and sense of humor attracted her.

“You cannot deny that he was a good-looking dude,” she told me via WhatsApp from Stuttgart. “His eyes were just so kind. He had these stupid, ridiculously long lashes that no guy needs and all girls want.”

They eventually fell in love and planned to get married. Meanwhile, Lisa noticed how sharing his story on stage took a lot out of Gordon.

“Sometimes, I got a little worried that speaking about it was taking a toll on him because it is kind of like being retraumatized,” she said. “Even though he was exhausted and it was a lot, that was something he lived for — making sure that no one else had to go through what he had to go through.”

Credit: Courtesy of Lisa Köngeter

Credit: Courtesy of Lisa Köngeter

On their first date, Lisa asked about Gordon’s tattoos. One on his right arm declares: “You do not have to be good.” He told her it comes from the late Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Mary Oliver’s poem, “Wild Geese.” Now among my favorite poems, it is simultaneously sad and sweet, comfortingly reminding us that the natural world goes on despite our despair:

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Lisa movingly recited that poem in German at Gordon’s Dec. 11 memorial service in the East Roswell Recreation Center’s gymnasium. As she spoke, I glanced around the gym and witnessed the substantial impact Gordon made in life. Hundreds of mourners had filed inside to remember him. His family moved the event from a smaller venue to the recreation center after learning so many people wanted to attend. Many of them, like me, wore black-and-white striped lacrosse referee shirts in solidarity with Gordon.

Together, we championed his motto: “Take care of your crew.”

Need help? Call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988. Donate to the Gordon Corsetti Mental Agility Foundation at www.everloved.com/life-of/gordon-corsetti/donate/

Credit: Courtesy of Lisa Köngeter

Credit: Courtesy of Lisa Köngeter

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured