Georgia women’s college quietly drops class names tied to Klan history

For more than a century, Wesleyan College for women has clung to class names cast from an era when the school openly celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and fostered initiation ceremonies that used nooses, Klan-like robes and rituals held by torchlight in the dead of night.

Many of these traditions continued for decades after the 1960s when the first African-American students entered the Macon school, which proudly touts its storied place as the oldest chartered college for women in America. Methodist ministers founded the school in 1838.

Now, as the school readies for fall classes that start next Monday, one of the last vestiges of its racist past has suddenly vanished. School officials on July 24 announced they are abolishing Wesleyan's use of its four class names over concerns they link directly back to the most menacing parts of the institution's history.

“We believe it was important we move away from the class names totally,” said Wesleyan President Vivia Fowler. “We want to create a better community for our students.”

The decision to eliminate the class designations such as the “Green Knights” and the “Purple Knights” has drawn both praise and anger.

It is part of a broader effort over the past 13 months by school leaders to seek racial reconciliation and healing after a series of racially charged incidents roiled the tiny campus of 700 students. As part of the effort, the college updated its official history on its website the day it announced elimination of the class names.

The new history includes a more comprehensive view of its past and fuller inclusion of African Americans to its story. Contributions of African Americans from the school's earliest days when slaves worked on campus are now a part of the school's story.

Fowler said reactions to the elimination of class names have run the gamut. A few people have said they will no longer be involved with the school, while others have fully embraced the change, she said.

“It’s been a very emotional conversation for many,” she said. “Some people have asked questions about why we’ve taken this action without having read the revised history. It’s not that they don’t want to accept it. It’s they truly don’t know.”

‘Something much bigger than Wesleyan’

Dana Amihere, an African American alumnae who graduated in 2010, said the change is long overdue.

She experienced the racist traditions almost from the day she stepped on campus in 2006 as a first year student. As editor of the school paper her senior year, she oversaw a series that questioned some of the traditions, but many in leadership still weren't receptive to change.

Still, she’s been surprised by the social media response over the past week revealing a significant group of alumnae who want to hold onto the past. Even with the class names eliminated, she’s not sure the school will ever fully let go of its racist past.

“I don’t see it going away anytime soon,” she said. “We’re in the throes of something much bigger than Wesleyan.”

Many of those most troubled by the change are white alumnae who date to a period when there were no or very few black students. Today, the school of 700 students touts itself as one of the most diverse small colleges in the country, with roughly 25 percent African American enrollment.

When racist graffiti appeared on dorm walls in January 2017 leaders canceled class for a day. Someone wrote the N-word in black marker and targeted an international student with offensive language.

African American students were hurt and angry. The fact that successive generations of school leaders had downplayed the college’s history seemed to add to the mistrust and tensions.

Leaders slow to recognize history

The class names played a central role in this past. Myths surfaced over the years that seemed to mask the true origins and added to the intrigue. An Atlanta Journal-Constitution article in July 2017 outlined much of this history. School officials for the first time formally acknowledged the racist past and apologized within hours of the article's digital publication.

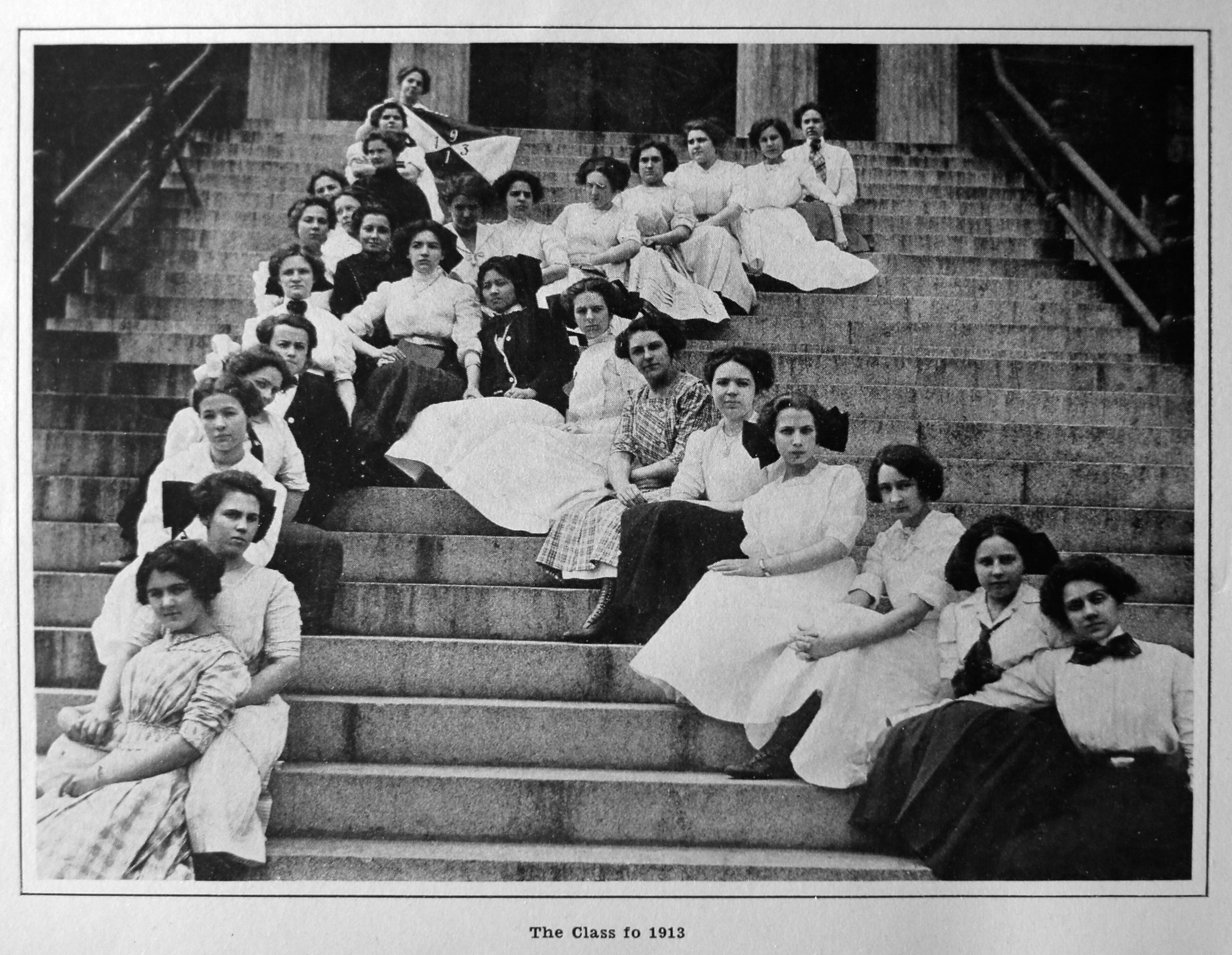

Class names first appeared on campus in 1909 when that year’s seniors called themselves the Ku Klux Klan. The class four years later utilized the Ku Klux Klan name and that year’s yearbook was titled Ku Klux. Eventually the name changed to the Tri-Ks, then morphed into the Tri-K Pirates before the school dropped Tri-K and simply used the Pirates starting in the 1990s.

Other class names created after the Klan moniker included the Green Knights, the Purple Knights and the Golden Hearts. For nearly a century, each new incoming class adopted one of the four names on a rotating basis. The freshman adopted class colors, cheers and went through an initiation process that for years incorporated hazing.

Judi Durand was in the freshman class of 1991 that opposed the use of the Tri-K Pirates name and fought the use of nooses during the school's initiation rituals. The college got rid of the nooses and dropped the Tri-K from the Pirates name during her time on campus, but refused to eliminate the class names altogether.

She said it’s shameful that it took all these years later for the names to go away. She’s not surprised, but is disheartened that some in the Wesleyan community still oppose the change.

“I feel like they only did it because they absolutely had to,” Durand said. “I think it’s an insult and disgrace it took this long.”

Our reporting

In a series of stories in 2017, the AJC exposed Wesleyan College’s use of symbols and rituals borrowed from the Ku Klux Klan at the turn of the 20th century. African American students recounted harrowing stories of feeling intimidated by hazing rituals inspired by the Klan. The AJC also chronicled the college’s efforts to change. Today’s story details a new effort at the Macon college to make amends.