Georgia research illuminates property thefts endured by Cherokees

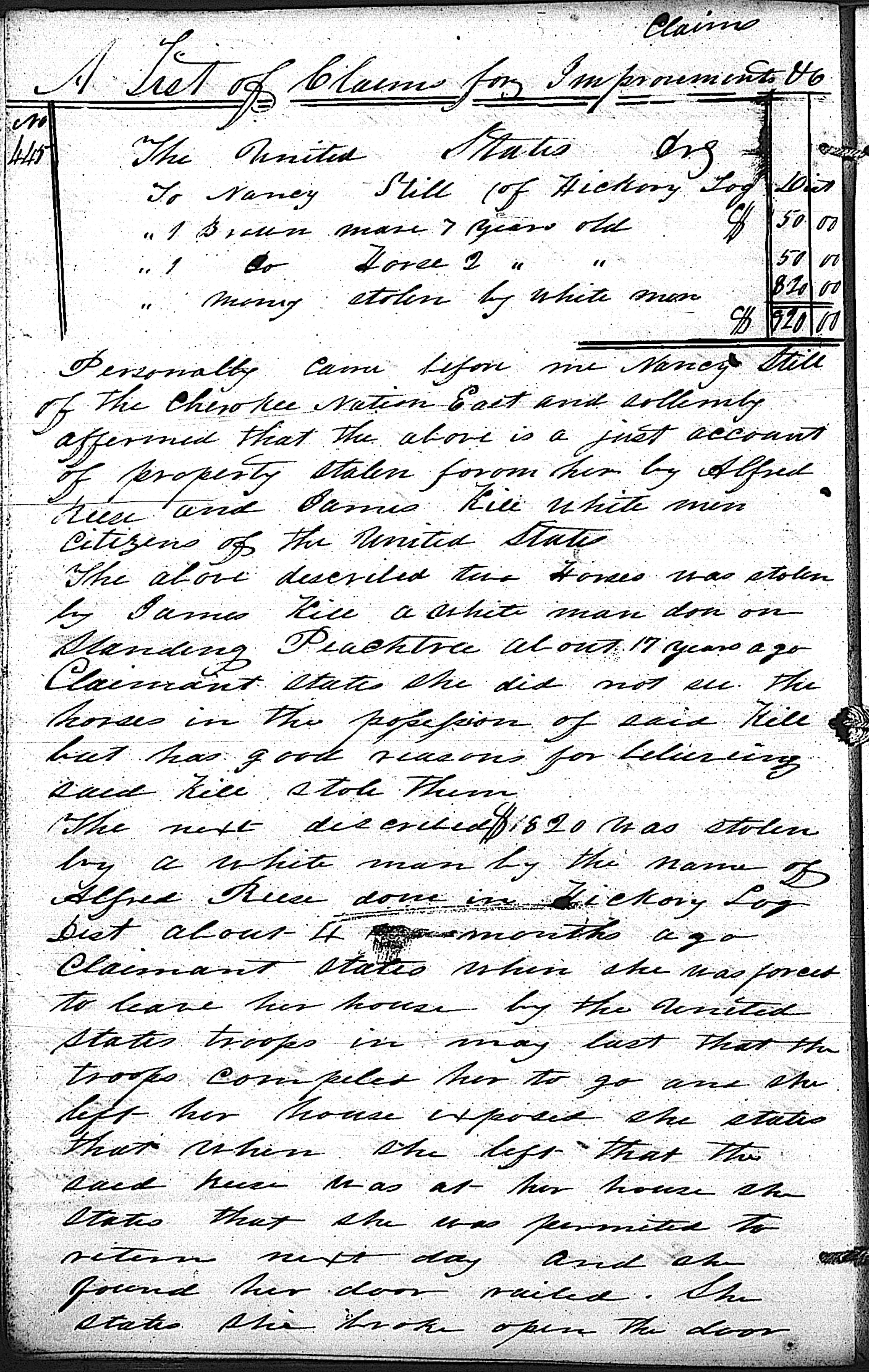

In September of 1838, Nancy Still filed a claim to recoup $820 she said was stolen from her after federal troops expelled her and other Cherokee from their homes in what is now North Georgia. Forced to migrate west to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears, thousands of Cherokee died on the way.

“The troops compelled her to go and she left her house exposed,” a Cherokee claims agent wrote of Still’s account. “She was permitted to return the next day and she found her door nailed. She states she broke open the door and found her trunk broke open and her money gone.”

Other claims filed by Cherokee living in the same region say authorities forced them to abandon their land, crops and livestock. Some alleged a notorious band of Georgia thieves called the Pony Club stole their horses and cattle. One mentioned being “whipped” by white men he accused of stealing his rifle, sheep and hogs.

Illuminating a tragic part of American history, researchers at Reinhardt University are transcribing such handwritten legal documents and making them available to the public online. The painstaking work comes as the university is preparing to host a two-day gathering this weekend exploring the history of the Cherokee.

Chuck Hoskin Jr., the Oklahoma-based Cherokee Nation’s principal chief, said he appreciates Reinhardt’s work because it helps document his people’s history and the atrocities they endured.

“It’s good in terms of keeping the memory of that chapter of American history alive,” said Hoskin, who has traced his heritage to Georgia and has obtained a copy of a claim an ancestor from McMinn County, Tennessee, filed for a log cabin, bricks, eight acres and 46 peach trees.

Other Cherokee filed claims for houses, livestock, guns and even slaves.

“This wasn’t the dominant aspect of our economy. It is not the whole of the story of pre-removal Cherokees. But it is a part of the story we have to confront and that is that we enslaved Black people under our own laws,” Hoskin said. “It will not surprise researchers and it does not surprise me that there were claims of some Cherokees for property that happened to be human beings.”

Reinhardt’s research builds on work by Michael Wren, a historian from Sandy Springs, and other volunteers at the National Trail of Tears Association. The nonprofit was formed in 1993 through the efforts of the U.S. National Park Service and the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Advisory Council. The principal chiefs of the Cherokee Nation and the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians signed the association’s corporation papers.

The association is making scanned copies of original Cherokee claims available for free on its website. Those claims — which came from universities, the U.S. National Archives and other sites — contain handwritten accounts by agents appointed by the Cherokee. Commissioners representing the federal government, Wren said, “summarily dismissed every one of them.”

“The burden always falls on the person making a claim to prove their claim,” said Wren, chairman of the association’s research committee. “It was very much weighted against the Cherokee.”

The Cherokee filed some of their claims as Georgia and federal authorities sought to force them west. President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Around that time, Georgia passed laws making it easier for white people to dispossess Cherokee without the threat of legal consequences, according to Andrew Jones, a Reinhardt history professor. Georgia did that, he said, to “open up land to white settlement and in alliance with the wider goals of the Jackson administration.”

Meanwhile, looters and robbers targeted Cherokee property.

“Some of them really were bandits, like the Pony Club,” said W. Jeff Bishop, who directs Reinhardt’s Funk Heritage Center and who has worked closely with Jones in transcribing the Cherokee claims. “They just flooded in. They were rapacious. They took what they wanted.”

Transcribing the Cherokees’ handwritten claims is difficult time-consuming work that involves paleography, or deciphering historic documents. Working as interns as part of the Cherokee Voices Project, Reinhardt students are learning history on the job.

“I really just enjoy getting to be part of this process of documenting this history that people can use and that Cherokee descendants can use,” said Dakota Youngblood, a history student at Reinhardt. “Getting that hands-on experience has been wonderful. And being able to help people in the process has been really nice.”

Fellow Reinhardt history student Avery Murray agreed, saying each claim helps “put a face and a name to a part of history.”

As for Nancy Still, she filed multiple claims and was eventually forced west to Oklahoma, where she survived into her 70s, according to Wren. He tracked her to Oklahoma through a will.

“They survived. They overcame. And they flourished in the west. That doesn’t excuse what happened to them in the east at all,” Wren said of the Cherokee. “But they didn’t let the misfortunes define them in the rest of their lives.”