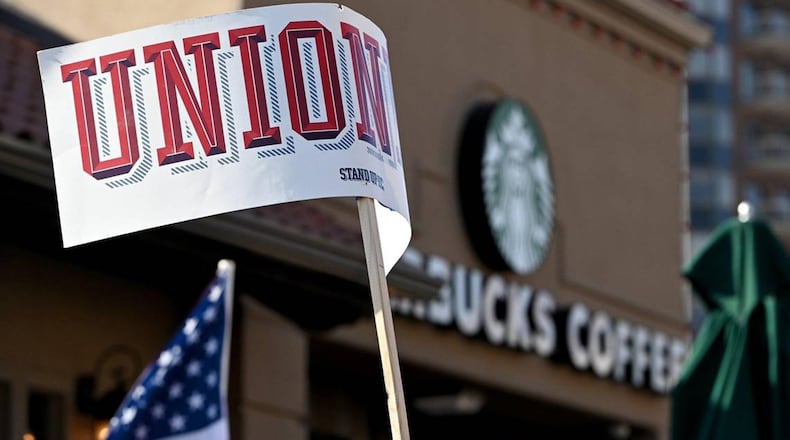

Workers at metro Atlanta stores belonging to Starbucks and Apple, two of the world’s most powerful brands, will soon vote on whether to join unions, a pair of high-profile showdowns that are likely previews of organizing drives to come.

In a vote overseen by the National Labor Relations Board, workers at a Starbucks store on Howell Mill Road in Atlanta will decide on Friday whether to form a union capable of bargaining for wages, hours and working conditions. A similar vote is slated for June 2 for workers at the Apple store in the Cumberland Mall in Cobb County.

Both drives are connected to national efforts to unionize workers at the two corporate icons. And both campaigns are being aggressively opposed by the companies.

In Georgia, virtually any organizing drive stands out. The state has a long, non-union climate, that includes “right to work” laws that crimp union fund-raising.

Just 5.8% of the workforce in Georgia is a member of a union, ranking 43rd among the states, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. So far, the organizing action seems to be limited to a small number of places, but activists say the current drives portend a larger trend, and they expect to keep winning.

“I am super-optimistic now,” said Page Smith, a barista at the Howell Mill Starbucks. “People who were slightly interested are extremely interested now because of the behavior and response of the company. They want to make sure that their voices are heard.”

The first U.S. Starbucks store to unionize was in Buffalo, New York, last fall.

Since then, more than 72 elections have been held at Starbucks stores with employees voting for a union at 60. And the $29 billion-a-year chain that remade the market for coffee and for many years touted its worker-friendly attitudes, has pushed back.

Founder Howard Schultz, who returned to the post of chief executive earlier this month, said that the company would be giving raises to non-unionized workers, but not to those who joined unions. Workers in Atlanta-area Starbucks say that anti-union information is commonly displayed in staff areas and that managers read anti-union statements to workers.

A spokeswoman for Starbucks said the company doesn’t think unions are needed.

“Our hope is that the union will respect our right to share information and our perspective just as we respect their rights,” she said. “We believe we are better together as partners without a union between us.”

Ben Scott, who works at a Starbucks in Covington, said he makes $12 an hour, up from $10 an hour when he started a year ago, but he has to work other jobs to pay his half of the rent for an apartment he shares with his girlfriend.

To get the job he had to sign an agreement that forbids him to work at any other coffee shop, he said. “I am looking to get rid of that. I think it’s just a power thing.”

Apple, too, has long promoted itself as a great employer that appreciates its workforce.

The company provides “very strong compensation and benefits,” Apple said in a statement. “We are fortunate to have incredible retail team members and we deeply value everything they bring to Apple.”

Employees do feel affection for the company, said Sydney Rhodes, who works as a “creative pro” at Apple’s Cumberland Mall store. But she said Apple’s handling of pay and hours is a challenge to workers who need to meet living expenses.

“We love Apple, and we want to stay,” Rhodes said. “At this point, we feel that this is the only way to get what we need, to have a legally binding contract.”

Apple is multi-trillion-dollar company, Rhodes said. Its annual revenue was $386 billion last year.

“There are ways for them to create long-term stability,” she said.

Apple’s website states its code of conduct for suppliers that requires them to let their employees organize without interference.

“If you set that rule for your suppliers, why not for your own workers?” Rhodes said.

An Apple spokesman declined to answer questions about its code.

Tough to organize

Unionized jobs make up a relatively low percentage of the overall workforce in Georgia. But there remain several enclaves, including skilled trades, teaching and some public sector jobs.

Unionized GM and Ford auto plants in metro Atlanta closed years ago, and the state’s textile industry, another sector that was partially organized, has been on the decline for years.

State officials use the lack of unions as a selling point when recruiting companies.

Currently, the state’s only auto plant is the non-union Kia factory in West Point. That factory employs more than 2,700.

Two future electric vehicle plants — Rivian, east of Atlanta, and Hyundai Motor Group near Savannah — are expected to collectively employ 16,000 and will likely be non-union.

The first Starbucks group in Georgia to approve a union was in Augusta where employees in April voted 26-5 in favor, said Jaysin Saxton, a shift supervisor at the store.

“I had this moment that day, thinking ‘Wait a minute, no other store has done this,’” he said. “This is a really big deal.”

He is hoping the union can negotiate for better parental leave, more generous sick time and better pay.

“I have a co-worker who has to be out for six weeks for back surgery and all they will do is hold her job,” he said. “And the pay is still below the living wage for the state of Georgia.”

Unlike many organizing drives of the past, the Starbucks drive is not fueled by resentment of the company, and is really no threat to its operations, said Nick Julian, a shift supervisor at the Ansley Mall Starbucks, who is also a graduate student.

Employees like their work, and they just want more control over their economic lives, he said.

“I didn’t come from a union family,” he said, “but I grew up with the understanding that union labor throughout time has allowed workers to achieve the proverbial American Dream.”

Share of workers belonging to a union

Georgia: 5.8%

United States: 10.3%

Median weekly pay

Workers represented by unions: $1,158

Workers not represented by unions: $975

Most commonly unionized jobs in Georgia: Public sector, telecommunications, education, skilled trades, film and grocery stores (e.g. Kroger)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured