Pearl Harbor: A love story finds its end 79 years later

On November 29, 1941, lonesome Boilermaker 1st Class Eugene Blanchard, from tiny Tignall, Georgia, wrote his wife Laura Ann from the battleship USS Oklahoma in Pearl Harbor.

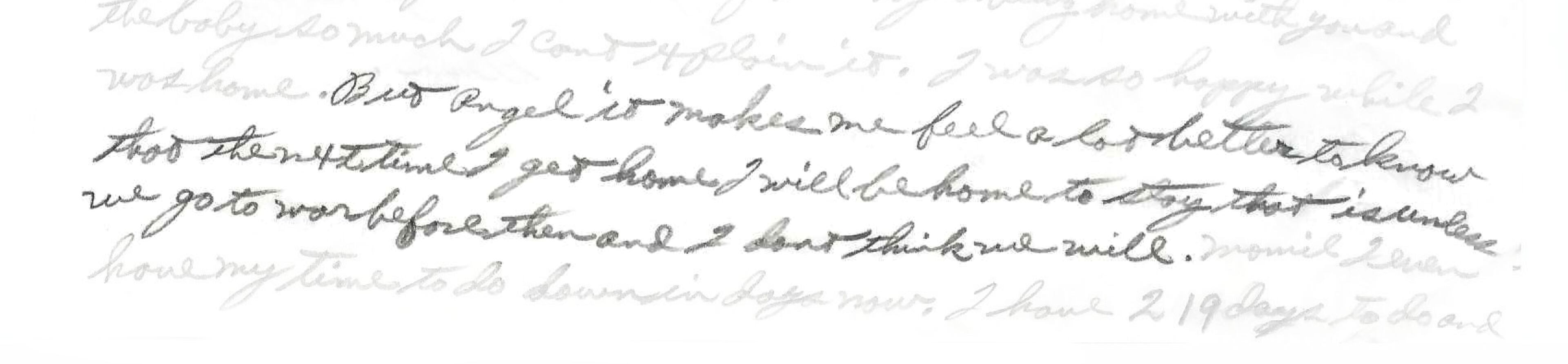

“Miss you and the baby more and more each day that goes by. I will be so glad when my time is up. Well, I have 5 months and 19 day left to go now.

... I don’t think there was ever a guy who wanted to come home more.”

Eight days later, the Japanese attacked the Hawaiian base, torpedoing the Oklahoma. It capsized in under 12 minutes, taking with it 429 crew members, including Blanchard.

Seventy-nine years and six months later, Gene Blanchard is coming home. He’ll be laid to rest in North Carolina, where his son lives, on June 7.

His remains and hundreds of others were unidentifiable for decades, buried in Hawaii as unknown sailors. It took a Pearl Harbor survivor’s tenacious commitment and advances in forensic technology to finally put names to bones so that the bodies could be returned to family members.

The baby whom Blanchard referred to in his letter is nearly 80 years old. Bill Blanchard doesn’t remember his father, but the man has always been a presence in his life.

Until now, the only tangible connections Bill had with his father were a brass ashtray engraved with USS Oklahoma and a lighthouse-shaped lamp that the boilermaker made and sent home. Each time Bill moved — to Washington, California, Alaska, Idaho, North Carolina — the lamp and ashtray came along.

“The lamp, it was always lit, like a beacon for my dad. And he is home finally,” Blanchard said from his home in Elizabeth City, North Carolina.

“Our family is intact. Thank God.”

Navy records given to the Blanchard family have helped bring details to to life about the 24-year-old sailor — describing him as 5-feet 7 inches tall and 120 pounds with two tattoos, an anchor on one arm, a woman on the other.

“We are finally getting to put a picture together to where you have more human emotion about it,” said Bill’s son, Chris Blanchard. “Because it has been so ethereal. It just feels much more real now.”

In 1936, when Gene joined the Navy in the middle of the Great Depression, Tignall was a deep piney woods Southern community. Even today, the rural outpost east of Athens, near the South Carolina border, has only one stoplight.

He left school at 16 years old, after the 10th grade, applied to the Naval Academy without success and then worked with his blacksmith father for three years before signing up, his family said.

“Our family is intact. Thank God."

On his Naval induction papers, he wrote one word as his goal in joining the service: “Career.”

The Navy gave him one, training Gene as a boilermaker before assigning him to the USS Oklahoma, a 20-year-old battleship. It was stationed in Pearl Harbor by 1940, but also had long stops for repairs and upgrades in California and Bremerton, Washington, the home of Laura Ann LaGasa, a dark-eyed, 5-foot-tall brunette.

The family doesn’t know much about the couple’s romance, other than the two eloped and married in Nevada on June 17, 1940. Gene was 22; Laura Ann, 18.

“I truly don’t remember a time when my mother and I sat down for an hour or two and went into anything about my dad in great detail,” Bill said, his voice cracking as he paused to gather his emotions. “I think she just wanted to hold that information close to her heart about my dad.”

He does remember that she attended many meetings of Pearl Harbor survivors over the years, looking for information about Gene. She died in 2007.

Bill’s daughter, Stephanie Blanchard, recalls her grandmother saying how she enjoyed resting her fingers in the waves of Gene’s dark hair. Laura Ann kept his letters from Pearl Harbor in a wooden Brown & Haley chocolate box.

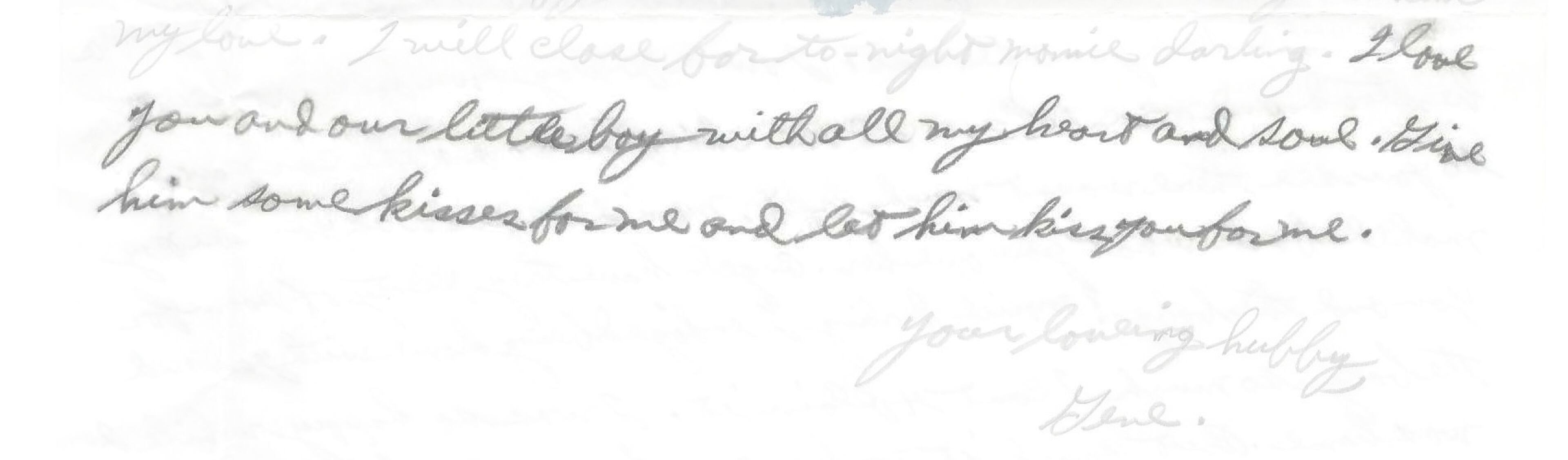

“I think he was the love of her life,” said Stephanie, who takes care of the letters that brim with love for his wife.

“Honest, Mommie, it seems to hurt me more and more each time I have to leave you,” he penned on Oct. 1, 1941. “Well, the next time your daddy comes home, you won’t have to worry about him leaving you again.

“... Angel, I love you and that darling boy so much that my heart aches for you both when I start thinking of you both and that is almost all the day and night.” He turned down a shore-based job — which, in retrospect, might have saved his life — because it would have left him with too much time to think.

Even after Laura Ann remarried, Gene’s picture was always up in her house, as well as the framed Memorial Certificate of his death signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

It was in 1987 that another letter arrived for Laura Ann from North Carolinian James Saul, one of Gene’s shipmates and friends who managed to escape the Oklahoma. It provided details about her husband’s last moments and words. Nine torpedoes ripped through the Oklahoma’s 13-inch steel plate sides, and it had rolled over quickly. Gene was trapped in a lower-deck compartment with Saul and about a dozen others, the water rising around them.

“All of his thoughts were of you and his son. He kept repeating over and over what is going to happen to his wife and son, please God take care of them,” Saul wrote.

Saul managed to dive to a submerged porthole, open it and wriggle through after four tries. “I could never find out if he made it through the porthole or not,” he wrote.

It took 18 months to right the ship and remove the remains of the sailors and Marines. The dead were buried together in mass graves in Hawaii but disinterred in 1947, when the navy made initial efforts to identify them using dental records and other references.

The Navy managed to identify only 35 men at that point and reburied the rest, said Kelly McKeague, a Georgia Tech graduate and retired Air Force major general. McKeague is now the director of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. The job of its 725 employees is to find and identify soldiers missing or killed around the globe and to bring them home.

A survivor of the Pearl Harbor attack, Ray Emory, began lobbying in the 1980s for the Oklahoma remains to be disinterred again so that new scientific testing, such as DNA, could be used. A partial disinterment took place in 2003 and, by 2010, six sailors had been identified.

In 2015, McKeague’s agency launched the Oklahoma Project with the goal of naming and sending home the remaining 394 men.

It was daunting to open those caskets containing bundles of bones that had been indiscriminately gathered into semblances of full skeletons and wrapped in blankets, project director Carrie LeGarde said. She is a forensic anthropologist at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, where the work is done. Early on, one casket contained five bundles, but bones showed DNA from nearly 100 different men, she said.

She and teammates began carefully matching the more than 1,300 bones, using forensics and searching for perfect fits between bones and joints.

The Service Casualty Office began tracking down families to ask for DNA samples.

Bill’s son, Chris, initially thought it was a scam after getting a letter.

“I kind of blew it off,” he said.

Bill Blanchard had heard on and off about attempted identifications, but “never, in a million years, I don’t think any of us would have thought this was going to happen.”

He got a letter in 2015 asking him to participate. Several first cousins, sons of his father’s sister, also were asked for DNA samples. With so many remains to test, cross referencing DNA from different sides of the family can help the investigators with identifications.

Then, in January, Bill got a phone call while watching TV. The agency had identified Gene, thanks to a DNA match from one of Bill’s cousins.

“Honestly, at the moment, I thought, is this a joke?” he said. “The person assured me, in fact, this is for real. And I said, ‘I am flabbergasted,’ and almost fell off the chair. I said, ‘My God, after all this time, he is going to be brought home.’”

The casket will contain his skull and many, but not all, of his bones. A uniform will be draped over them when the casket is flown to Elizabeth City, where Bill and Stephanie live on June 3, Bill’s 80th birthday.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s renewed efforts starting in 2015 to identify the remaining 388 unknown sailors and Marines who went down on the USS Oklahoma using advanced forensics, including DNA testing. More than 5,000 DNA samples from surviving family members were collected. To date, it has successfully identified 336 of those men.

“These men and women went off to combat, serving our nation and they paid the supreme sacrifice. And while their families know to this day they perished in combat there is still a void in heart and mind and in life that the loss leaves…For us, we not only have a sacred duty to our comrades in arms, but also duties to their families (to return their remains)…Not having that body back is truly impactful for them and they are still grieving because of the uncertainty that exacerbates their loss.” — Kelly McKeague, Director of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

Pearl Harbor

On Sunday morning, Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese Imperial Navy used six aircraft carriers and support ships to launch a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific fleet in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

The attack sank numerous U.S. ships and destroyed nearly 100 aircraft that were mostly on the ground. U.S. military casualties totaled more than 3,400, including more than 2,403 killed. The attack pushed the U.S. into World War II.

LeGarde said that, since 2003, the agency has identified 336 men from the Oklahoma. There has been a cascade of identifications in the last year — 52 since January, as years of work paid off.

The Georgians identified and returned home include John M. Donald, from Cherokee County; Archie Callahan Jr., from Atlanta; and Julian B. Jordan, from South Georgia.

The remains of only one Georgian are still unidentified, Walter B. Manning, one of Blanchard’s shipmates. LeGarde said the agency has family DNA samples, and she is hopeful.

Gene will be buried in a plot that is within a stone’s toss of the monument to Elizabeth City’s lone Pearl Harbor casualty, a sailor from a ship that was moored next to the Oklahoma.

About a year ago, Stephanie had the lighthouse lamp rewired and put it in her house.

“As soon as I plugged the lamp in, I said to Gene, ‘I am going to leave this light lit night and day so you can find your way home to us,’” she said. “And, sure enough, here we are.”