Georgia may have gotten its dream ruling at the Supreme Court this week, but that doesn’t mean the Southeast’s decades-old water wars will be over anytime soon.

Cases are pending in lower federal courts that involve two Georgia river systems. And Georgia can be sued by Florida officials again if they think the state’s water use is unreasonable during any future droughts.

Thursday, the Supreme Court ruled against Florida, which had argued that Georgia residents’ behavior during the 2012 drought killed its iconic oyster industry in the Apalachicola Bay. Florida was seeking a decree from justices limiting how much water Georgia farmers could take from the Flint River for irrigation.

Lara B. Fowler, an environmental law professor at Penn State, said if circumstances on the ground change – if populations grow, industries shift or extreme weather occurs, for example – the states could return to the Supreme Court. She cited Colorado and Kansas, which have a water dispute that justices have ruled on seven times over the years.

But “Florida lost and lost hard in this circumstance,” Fowler said. “I don’t think they could ask the court to rehear this case and would get anywhere.”

Ryan Rowberry, a Georgia State University law professor, said Florida could shift its tack and make legal claims under other federal laws like the Endangered Species Act or Marine Mammal Protection Act. Thursday’s ruling, he said, “in no way exhausts all of Florida’s legal remedies.”

“All this does is settle who’s responsible for the 2012 drought,” added Rowberry, who was part of Florida’s legal team between 2008 and 2010.

A spokeswoman for Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody said her office was reviewing the Supreme Court’s opinion and consulting with the state Department of Environmental Protection “to discuss if any further action is warranted.”

Lower level cases

More immediate legal threats to Georgia’s water supply are currently making their way through federal district courts.

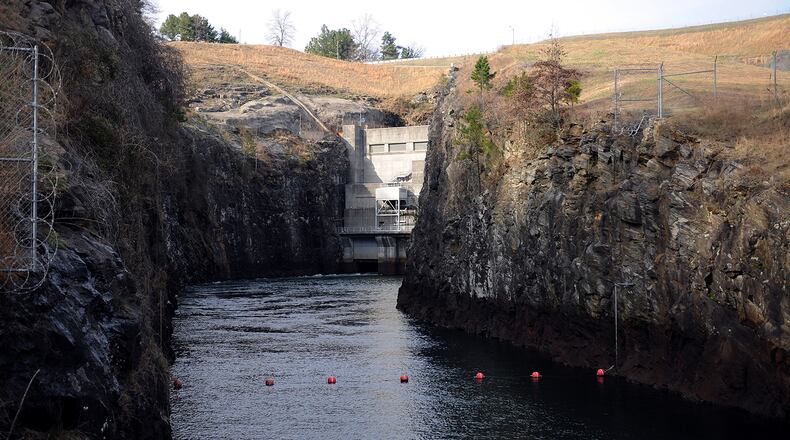

Alabama, which sat out of the Supreme Court case but backed Florida, has filed two suits that challenge the way the federal Army Corps of Engineers plans to divvy the water in its dams along the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) and Alabama-Coosa-Tallapoosa (ACT) river basins in the decades to come.

Credit: Atlanta Regional Commission

Credit: Atlanta Regional Commission

The ACF was the river system at the heart of Florida’s Supreme Court case. It begins northeast of Lake Lanier and meanders along the Georgia-Alabama border and through southwest Georgia into the Apalachicola Bay. The ACT originates in North Georgia with the Etowah River, incorporating Allatoona Lake and flowing through the heart of Alabama before ending its run in the Gulf of Mexico near Mobile.

Alabama believes the corps is holding back too much water in Georgia, leaving inadequate amounts for downstream users.

“Alabama has a need for the water in both the ACT and ACF basins just as much as Georgia and Florida do,” said John Neiman, who represents Alabama. “The real problems occur during droughts.”

The ACF case is being heard by U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia. It has been consolidated with a legal challenge from environmental groups that argues the corps did not adequately take into account the ecological value of the Apalachicola Bay in its water-sharing plans. Both sets of plaintiffs want the corps to revise its blueprint to release more water from Allatoona and Lanier.

Credit: Great Lake Allatoona Clean Up

Credit: Great Lake Allatoona Clean Up

Georgia, the Atlanta Regional Commission, city of Atlanta and governments throughout the metro area have intervened on the side of the corps in both the ACF and ACT cases. The river basins account for about 80% of metro Atlanta’s water supply, helping sustain millions of Georgians.

“Lake Lanier, Allatoona Lake, the Chattahoochee and the Etowah rivers are the biggest sources of water for metro Atlanta, and we do not have alternate supplies,” said Katherine Zitsch, managing director of natural resources for the commission, which oversees the region’s water plan. “Anything that puts a question mark on our ability to withdraw water from those sources is a challenge we’ll have to overcome.”

Legal observers believe the high court’s decision will have only a nominal effect on the Alabama cases. But Fowler believes it could have an impact on the types of evidence presented in water rights cases, since Florida’s was so poorly received by the Supreme Court.

Compact comeback?

Now that the Supreme Court case is over, Georgia, Florida and Alabama are under renewed pressure to negotiate water-sharing compacts for the ACF and ACT to prevent costly litigation in the future.

The three states, which began tussling over water 31 years ago, entered into similar compacts in the late 1990s but let them expire after governors couldn’t agree on the terms of their renewal.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

After years of facing off in court, fierce political rivalries may make it hard for the neighbors to come together again.

Still, Georgia State’s Rowberry said it’s incumbent on leaders to hash out an agreement.

“Courts are ill-equipped to speedily address these kinds of issues, so you have to have something politically, a playbook that you can go to and say, ‘We’re now entering a drought cycle, what kinds of things do we need to change to make sure everyone in the region is taken care of?’” he said.

“It’s been done before, and I think it can be done again,” he added. “I do think it will take some humility from all sides.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured