Confederacy leader’s Black, white heirs unbury past at Georgia estate

Crawfordville, Ga. — Anyone who has kept an ear cocked at a family reunion knows that these events are where secrets are finally spilled. The tongues that buried them have gone still. The excavated treasures and tragedies now become the property of blood relatives and strangers who sometimes are one and the same, linked by the common need to — in Southern parlance — find out who their people really are.

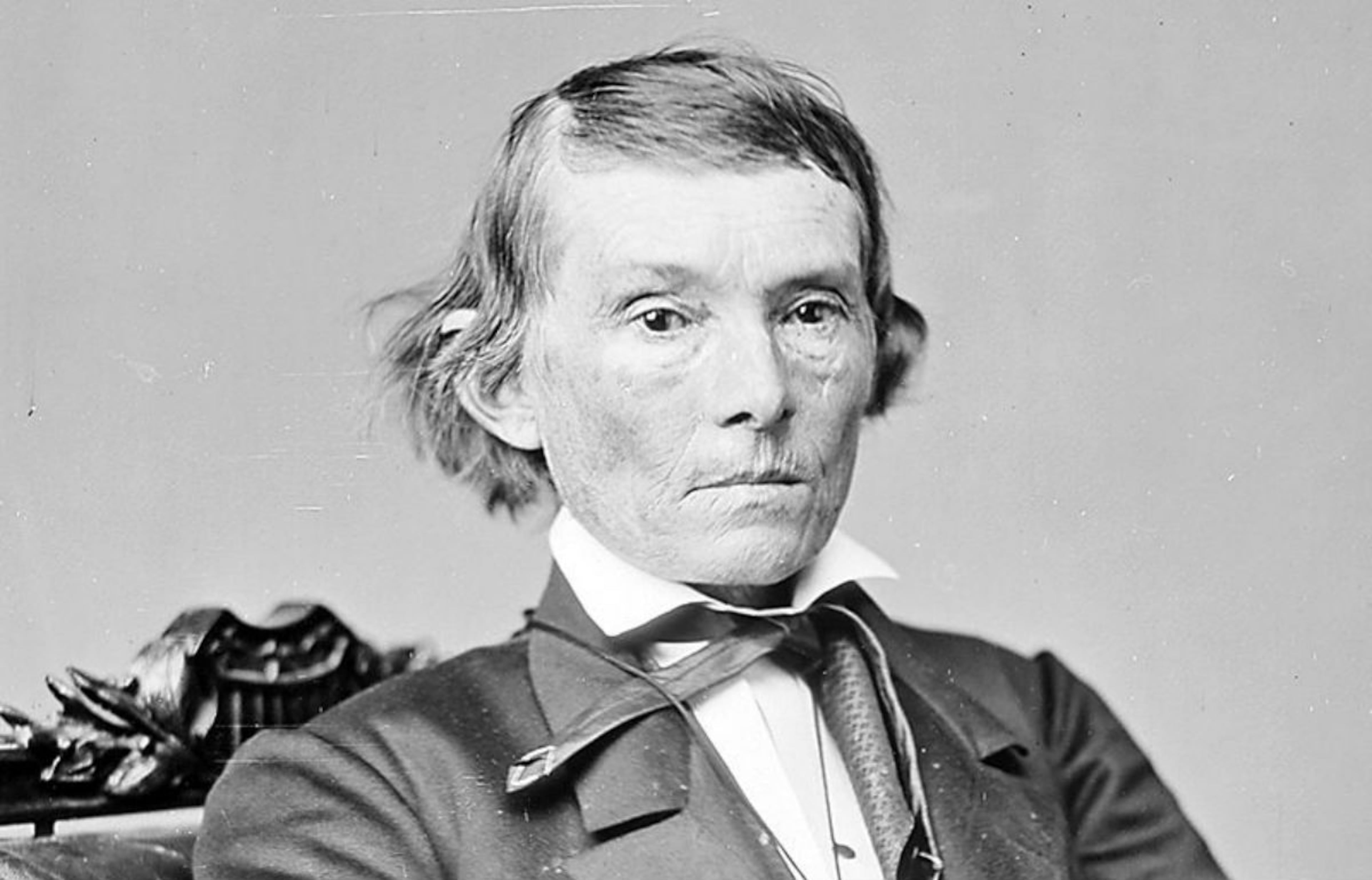

On this past Juneteenth weekend, there was no more important family reunion than the one that occurred at Liberty Hall, the estate-turned-state park that once served as the home of Alexander Hamilton Stephens, the first and only vice president of the Confederacy. He was a slave owner, too.

The hosts of the reunion were the Black descendants of Eliza Stephens. Family oral history says this enslaved woman’s first child, a son named Allen, was fathered by Alexander Stephens himself — a claim that thus far has escaped modern confirmation. The white guests were the Athens-based descendants of John Lindsay Stephens, Alexander’s half-brother. Lindsay Stephen’s son John was raised by his uncle Alexander at Liberty Hall.

That DNA testing has found no positive link between the two branches is less important than the indisputable fact that these two branches, descendants of enslavers and the enslaved, sprang from the same patch of clay — and were now gathered together under the shelter of Pavilion No. 3.

“Hello, beautiful people,” Jill Patton, a real estate investor from southern Florida, said in greeting. She then invoked the stunningly appropriate vision that will turn 60 years old in August, uttered by Martin Luther King Jr. from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood,” King had said then.

On this Saturday morning, the sisterhood was at the table, too. While the kids played soccer on a makeshift field.

The catered event was organized by Patton’s aunt, Elizabeth Coleman, the acknowledged First Historian of Eliza Stephens’ descendants and the recently retired pastor of a Presbyterian church in St. Petersburg, Fla. “We are gathered today in this place, to sit together at the table of brotherhood because we have made the choice to love. In spite of the past, of hurtful things, still we choose to love,” Coleman said.

Individual introductions followed. Both sides of the Stephens family have done well. Several were teachers, retired members of the military, and medical practitioners. The gathering included at least two elected officials. On Eliza’s side was Cynthia Jenkins, a longtime member of the Newnan city council. On John Lindsay’s side was Lawton Stephens, a superior court judge in Athens.

Along with occupations, college football loyalties — which bridge both race and religion — were often declared as well and did much to break the ice that covers several hundred years of slavery and decades of Jim Crow. Fortunately, the first order of business was lunch. Attendees were encouraged to sit with someone they didn’t know, an act that would have been abhorrent to the former owner of Liberty Hall and his white contemporaries.

For those unfamiliar with him, Alexander Stephens has become the “go-to” figure when historians do battle with the myth of the Lost Cause, the after-the-fact alibi that the Civil War had little to do with the preservation and expansion of slavery. In a well-noted 1861 speech to the citizens of Savannah, one month before shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Stephens denounced a particular phrase in the Declaration of Independence — the one that says “all men are created equal” — as social, moral and political bunk. The “cornerstone” of the Confederacy would be white supremacy, the new vice president said.

Alexander Stephens, a lifelong bachelor with no acknowledged children, was governor of Georgia when he died in 1883. His will tied together the two most-discussed ancestors at this outdoor conclave in east Georgia. John A. Stephens, the white son of half-brother Lindsay, was the first name mentioned in the document. Eliza Stephens, now a free woman of color, was the second.

It was something to ponder as the barbecued chicken and potato salad disappeared and the gathering got down to family business. And family secrets.

Chandra Fears of Chattanooga, a retired social worker, and Gail Poole-Vaughn of Columbia, Md., both from the Eliza Stephens side, spoke of the frustration that came with tracing Black lineage. “I know you guys are wanting a family tree. That family tree will not be delivered today,” Fears said. The 1870 census was the first in the South to count newly freed slaves and their offspring by name. The next few decades were periods of much movement, with families morphing into extended networks.

But the two amateur genealogists agreed with historians on two important points. Alexander Stephens had a special relationship with the slave named Eliza. He paid for her eventual wedding to a neighboring enslaved human being named Harry, whom Alexander Stephens later purchased as well. Secondly, in the context of slavery, “kindness” is a heavily weighted word, but Eliza and Harry Stephens were comparatively well treated. They both learned to read and write. Harry became Alexander Stephens’ major domo at Liberty Hall.

“Harry really managed the plantation,” Fears said.

“It was unheard of,” Poole-Vaughn added.

Then it was time for a second Alexander Stephens to speak — a real, live one who’s finishing up a doctorate in history at the University of Michigan. The living Alexander M. Stephens was partly responsible for this biracial meeting. And yet his was the hardest task of the afternoon — for he had to explain why his white family had been so long enamored with the long-dead Alexander H. Stephens, to the point of bestowing on him the ancestor’s name.

“I checked and ‘Andrew’ was available,” he said.

In August 2017, after a violent white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., Alexander M. Stephens and his brother Brendan Stephens wrote an open letter to Georgia state lawmakers on behalf of their entire family. They urged legislators to remove the statue of Alexander H. Stephens that sits in Statuary Hall of the U.S. Capitol, one of two allotted to each state. (The Stephens statue is still there today.)

Three years later, Jill Patton — the Florida real estate investor on Eliza Stephens’ side — wrote a similar letter, but it also contained the accusation that Alexander H. Stephens had raped her ancestor. That missive landed in my lap. I helped connect the two descendants.

On Saturday, Alexander M. Stephens said his father, mother, aunts and uncle all came of age on the right side of the Civil Rights movement. Nonetheless, he read this from that 2017 letter:

“We grew up with the hazy view of history that results from selective remembering, and we inherited ‘Lost Cause’ myths that emerged after the Civil War to sanitize the Confederacy and justify Jim Crow. We learned that Alexander H. Stephens initially opposed secession, but not that he spent his entire political career maneuvering to preserve and expand slavery… We learned the name of Stephens’ dog. But nobody around us ever quoted or even mentioned the ‘Cornerstone Speech.’”

The living Alexander Stephens added another factor to his family’s attachment to the dead Alexander — a story that Eliza Stephens’ relatives likely had never heard. At the close of the war, Alexander H. Stephens was a member of a small contingent of rebels who met with President Abraham Lincoln for an unsuccessful peace parley.

The Confederate vice president’s nephew, John A. Stephens, was being held as a prisoner of war. Alexander H. Stephens asked for his release. Lincoln complied, and had the young man brought to the White House. The Confederate lieutenant carried back to Richmond a letter from Lincoln to his uncle, asking for the release of a United States soldier of similar rank. The letter now rests in the archives of the University of Georgia.

“It’s a story that makes it a bit easier, for me at least, to understand the reverence that so many people in our family over the years have had for Alexander,” his namesake said. “After all, he ensured our ancestor’s freedom.”

But the living Alexander M. Stephens himself wasn’t wholly convinced. If Alexander H. Stephens believed that everyone who lived and worked at Liberty Hall deserved the same thing, he added, “maybe his name would be worthy of passage to the next generation.”

The living Alexander Stephens was followed by Emily McClatchey, a Cambridge, Mass., psychologist turned historical researcher. Other than myself, she was the only outsider who attended the Saturday session. The next stop for the reunion attendees would be the Liberty Hall grounds and museum. McClatchey offered some significant corrections to what they were about to see — and not see. For instance, there is the matter of Eliza Stephen’s age when she was purchased.

“Eliza gave an interview in 1912, five years before her death, to The Jeffersonian newspaper. In it, Eliza described being put up on the auction block. She was not 12 years old, as the museum tells us. She was six,” said McClatchey, an Athens native.

The elderly woman said she was given a beautiful red dress to wear on the auction block. Alexander H. Stephens bought her on a lark. Why were the extra years added? Possibly to ease the image of a little girl being ripped away from her family, McClatchey surmised.

After the war, Eliza and Harry Stephens prospered. In 1872, they built a two-story, nine-room house on land near Liberty Hall. Harry Stephens died in 1881, leaving $20,000 to his family — a remarkable amount for a former slave in rural Georgia. His widow lived in the house with a daughter, Dora, for the next 45 years. Yet on the grounds is the replica of another structure.

“The story you’ll hear today is that the two-room slave cabin — that was reconstructed in 1933, by the way — was where Harry and Eliza belonged,” McClatchey said. And what happened to the nine-room, two-story house built and owned by former slaves? Eliza Stephens left it to her daughter Dora. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the United Daughters of the Confederacy sought to turn Liberty Hall into a shrine to Alexander H. Stephens and the Confederacy — which would eventually be turned over to the state. Dora Stephens’ ownership muddied the situation.

McClatchey read from a letter that a UDC officer wrote, spelling out the problem to her fellow members: “The land on which Liberty Hall, the home of Alexander H. Stephens, is situated on consists of 12 acres. By the side of the Liberty Hall lot, and between it and the street, is attractive land containing about eight acres on which there is a two-story dwelling. And in my opinion, it is very desirable that this property should become a part of Liberty Hall on account of its proximity to it, and because of the further fact that it is owned and occupied by Negroes.” The last words of the final sentence were underlined, McClatchey said.

Upon her death, the UDC maneuvered the house away from Dora Stephens’ heirs. A museum extolling the virtues of the Confederacy sits there now, dedicated in 1952 by Gov. Herman Talmadge. All in all, that’s a pretty big family secret — and a relatively modern one at that.

I was not there, but the Stephens family reunion continued on Sunday. Elizabeth Coleman, the Presbyterian pastor, led a worship service of reconciliation outside Liberty Hall. Hymns were sung. Prayers were said. Wreaths were laid at the graves of Eliza Stephens and Alexander H. Stephens. Most importantly, sins that had been committed on this patch of clay were read out — and those who committed them were forgiven. For that’s what reconciliation is all about.

--Jim Galloway, a former political columnist for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, retired in 2021.