Georgia-born Blassingame changed how we view the history of slavery

Editor’s Note: This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

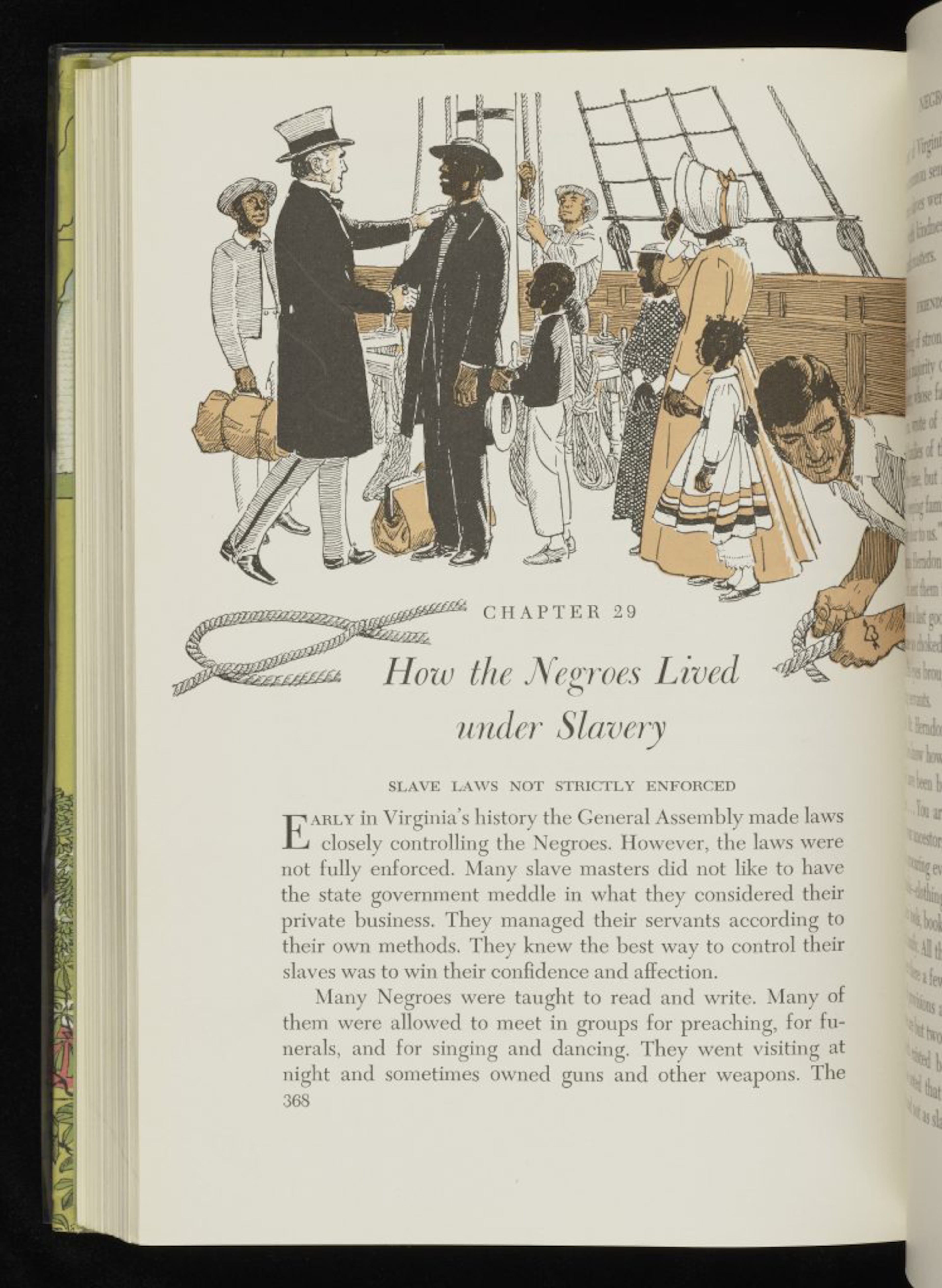

When Newton County native John Blassingame was a boy, school children in Georgia were taught that slavery in the American South was a largely compassionate institution that civilized African Americans at the expense of the slaveholder and the South as a region.

That view of slavery was perpetuated by influential historians like Ulrich B. Phillips, who grew up in LaGrange, graduated from the University of Georgia, and taught history at Yale University until his death in 1934. The mythology of the benign slaveholder and the docile slave, based largely on the records of Southern slaveholders themselves, was the dominant narrative taught to Black and white children in schools across the nation, but especially in the South where the idea of the Lost Cause was a powerful tool in maintaining the social order of segregation.

But Blassingame, who was born in Covington in 1940 and spent his childhood in Social Circle, grew up to challenge that narrative by unearthing the voices of the slaves themselves, who told a story of resistance and resilience despite brutal oppression and violence.

“He’s really the leader of this enormous, tremendous shift in the approach to the history of enslavement in the United States, because he took the perspective of the enslaved people,” said Mark Smith, a history professor at Fort Valley State University, a historically Black college in middle Georgia where Blassingame earned his undergraduate degree in 1960.

Blassingame’s most influential work, “The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South,” published in 1972, is widely considered a cornerstone work that changed how American slavery was understood and taught. The book used narratives of former slaves, collected during the Great Depression but long ignored by white historians, to reveal the vibrant culture and family structures created by African Americans in defiance of white enslavers and overseers.

Gerald Jaynes, a Yale professor of economics and African American studies and a colleague of Blassingame, said “Blass,” as he was known to his friends, grew up being taught a version of Southern history that rested on “a bed of inaccurate, distorted facts.”

But that history did not match the reality Blassingame knew from his upbringing in Social Circle, at a time when some of the elders in his community would have been the children of former slaves, Jaynes said.

After graduating from Fort Valley, Blassingame went on to graduate school at Howard University, and finally, Yale where he earned his doctorate and was invited to join the faculty. Jaynes said Blassingame’s personal background and scholarly path prepared him to confront the official history of slavery.

“If you think about it that way, he had no choice but to resist,” he said.

Blassingame faced criticisms from white historians of South history for using sources like the slave narratives. Many historians had disregarded the more than 2,300 first-person accounts of slavery as untrustworthy recollections taken down decades later, despite the consistency of those stories.

“We think about Blassingame’s major contribution to historical study — which applies directly to slavery, but goes beyond that — was that he gave historical Black Americans a voice,” Jaynes said. “He set all those former slaves’ voices free.”

There had been prior challenges by historians to the Phillips school of thought about slavery. Notably, Kenneth Stampp, a white historian, attacked slavery as both brutal and profitable, contrary to the assertions of Phillips and others. But this interpretation still did not view enslaved African Americans as anything other than victims of an oppressive system.

Blassingame focused less on the brutality of the enslaver and concentrated his analysis on the vibrancy of the community built by the enslaved.

“He shows that they have the resiliency to create their own community, to create their own culture,” Smith said. “That, in and of itself, is a form of resistance — just resisting the system and the attempt to break them to the will of others.”

“After Blassingame, no one could write about slavery in the United States and ignore the Black voice,” Jaynes said.

Even so, there is little public recognition in Georgia for Blassingame, who died in 2000 in Connecticut. A historical marker outside of LaGrange memorializes Ulrich Phillips as a “noted Georgia historian,” but no such marker exists for Blassingame in Newton County or anywhere else in the state.

Smith said there was an effort to create a scholarship in his honor at Fort Valley shortly before the money for it dried up in the economic downturn of the Great Recession of 2008. Smith said the effort needs to be revived.

“In terms of scholars to come out of the university and go on for graduate work elsewhere, his is probably the biggest impact that I think that Fort Valley State has probably produced in the academic community,” he said. “We need to do a better job of remembering that legacy.”