Georgia and abortion without Roe: Comparing 1972 and today

In October 1972, a few months before the U.S. Supreme Court overturned abortion bans, an Atlanta Constitution article chronicled the experiences of 15 women who wanted to end their pregnancies.

One recounted waking up at midnight in a pool of blood because of an illegal abortion. Another remembered her doctor in Georgia telling her to “settle down and have the baby.” One took a judo lesson during her freshman year at the University of Georgia and hoped the coach would fall on her and trigger a miscarriage.

Half a century later, the ability of women in Georgia to get an abortion is again being sharply curtailed. On Wednesday, a court upheld the state’s “heartbeat” law prohibiting most abortions after about six weeks, before many women know they are pregnant. That ruling came after the Supreme Court last month reversed its January 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, ending constitutional protections for abortions.

The debate over abortion never went away. It likely will continue to be fought on medical, moral and law-enforcement fronts as Georgians weigh the rights of women and the unborn.

Much has changed since the last time abortions were mostly unavailable here in the late 1960s and early 1970s. But there also are similarities between then and today.

Back then, teenagers and women still had abortions in Georgia, a few of them legally, others illegally. If they had the money, they traveled to New York for the procedure. If they were poor or lived in rural areas, and if they were Black, their options were far more limited.

In some ways, history could repeat itself as abortion restrictions tighten again.

“Discrimination will occur among the poor,” predicts Dr. Roger Rochat, one of the lead authors of a study published in 1971 by the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the health impacts of Georgia’s earlier abortion ban.

And illegal abortions “will be disproportionately African American, and perhaps disproportionately refugees or immigrants from other countries who have other challenges in terms of getting health care,” predicts Rochat, now a professor at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health.

Historic twists, turns and rubella

Georgia’s current abortion law is among the most restrictive in the nation, banning most abortions after fetal cardiac activity is detected. It allows later abortions in cases of rape, incest, threats to the mother’s life, or if a fetus would not be able to survive.

It is not the first time the state has taken aim at abortion.

Georgia passed its first anti-abortion law in 1876, later than most other states. It criminalized the procedure except when it saved the pregnant woman’s life. If the abortion was performed before a woman could feel a fetus move, the law carried jail time of one to 10 years. If a woman could feel the fetus, it carried a felony charge punishable by “death or imprisonment for life.” The law was vague about whether both the doctor and the woman could be charged.

How we researched this story

We reviewed written accounts of abortion in Georgia, including historical documents, academic papers and news articles and op-ed pieces in The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution. We also reviewed epidemiological studies from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and interviewed one of the authors. We also spoke with area historians and local women who lived in Georgia before Roe v. Wade.

In 1968, Georgia became only the fourth state in the nation to ease its abortion ban. It allowed for abortion in three circumstances: cases of rape, threats to a woman’s physical and mental health, and fetal deformity. Unlike Georgia’s new law, the 1968 version did not make an exception for incest.

The 1964 rubella epidemic, which caused birth defects ranging from deafness to developmental delays, played a leading role in the push to ease the ban. Infected women began requesting abortions at Atlanta’s Grady Memorial Hospital in the early 1960s. Some women received abortions because of threats to their health, but others were turned away.

The same year, Atlanta became home to the first Planned Parenthood outpost in the Southeast.

The state’s small Catholic population opposed easing the ban, but it garnered support among Protestants, who were most concerned with protecting maternal health, according to some historians.

“The two things that sold legislators who were very conservative in this state, whether they were Democrat or Republican, was wanting better babies, better breeding and dealing with this public health problem,” said Ellen Rafshoon, a history professor at Georgia Gwinnett College.

Most abortions were still banned at conception in the 1968 law, stricter than Georgia’s new law, which bans them roughly six weeks into a pregnancy. Georgia politicians who supported easing the law in the 1960s never intended to fully legalize the procedure and turn the state into an “abortion mill,” as former Gov. Lester Maddox noted at the time.

Few options despite ‘mental health’ clause

Merry O’Dowd says when she was in high school in metro Atlanta in the late 1960s, she had one wealthier friend whose father paid for his daughter to travel to New York for an abortion She says other wealthy young women she knew were forced by their parents to carry their pregnancies to term.

“It was a very judgmental thing. It was shameful. So if (abortions) happened, people didn’t talk about it,” says O’Dowd. “They did it. They didn’t admit it.”

Under the new law upheld Wednesday, criminal penalties for performing an illegal abortion remain the same as before: one to 10 years in prison. But medical and legal experts say there are many unanswered questions about what doctors can and cannot do, including when treating women for possible miscarriages. Several Georgia prosecutors have vowed in recent weeks to not seek charges against those who violate the state’s new abortion law.

Historians say there is no evidence that criminal convictions against abortion providers or women were common in Georgia in the 1960s or 1970s. But there also were very few places women could go in the state for an abortion.

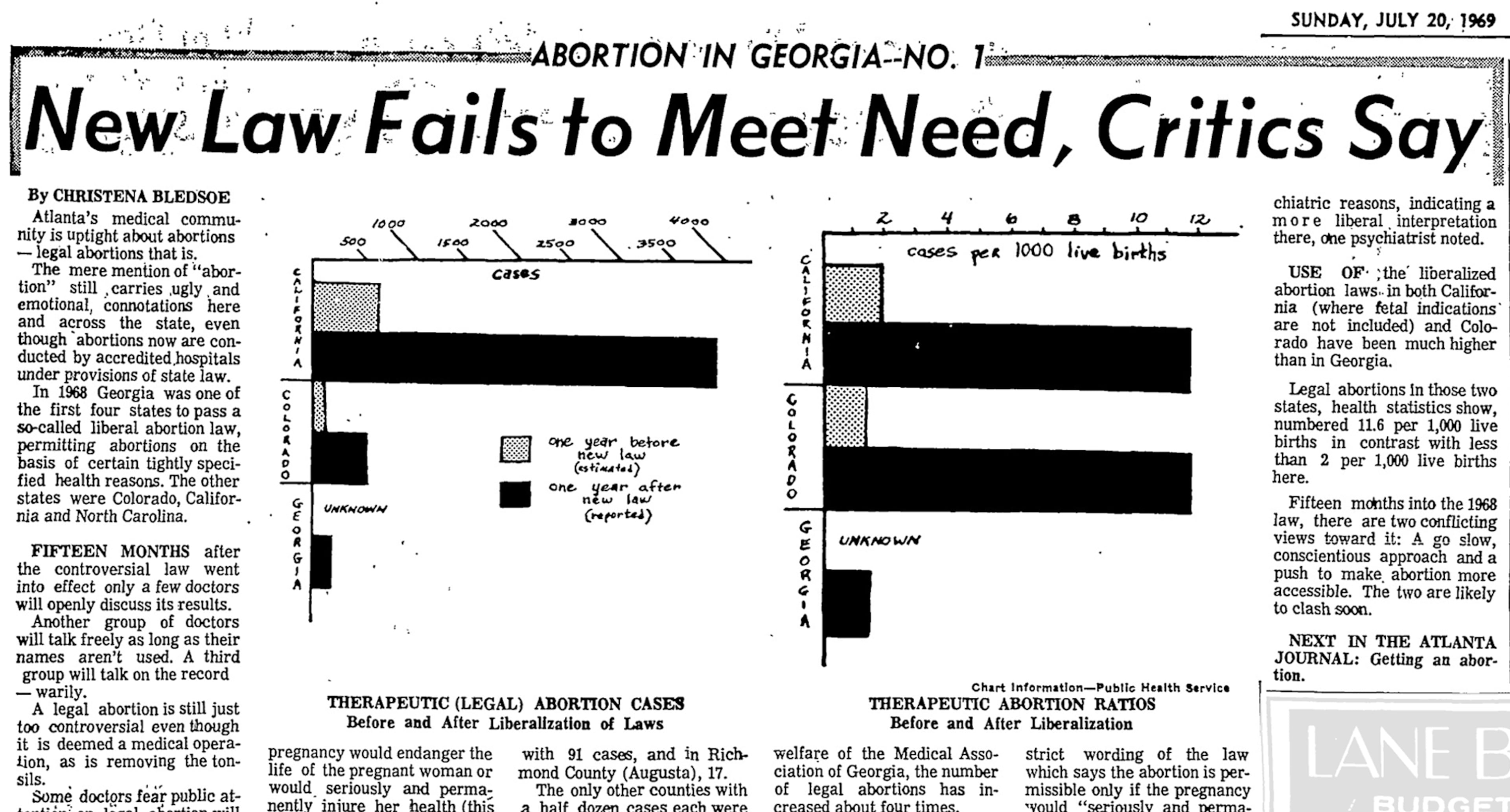

The 1968 law allowed the procedure for “mental health” reasons, broader than the new law, which focuses on the pregnant woman’s physical health. But the Atlanta Journal reported in 1969 that 140 of Georgia’s 159 counties hadn’t performed a single legal abortion. Grady Memorial Hospital had an unofficial cap of six abortions a month, according to Alex McGee, an archivist at Georgia Tech who wrote her thesis on the politics of abortion in Georgia.

Women had to gain the approval of three physicians and a three-man board at the hospital performing the abortion to legally end their pregnancies. For pregnancies that resulted from rape, the woman had to provide a police report, and her friends or family could go to court to bar her from getting the procedure.

“You had to really be in dire straits for doctors to take action,” McGee said. “Doctors didn’t want to be seen as doing too many.”

In 1968, there were 73 legal abortions in Georgia. The number more than doubled in 1969 to 168, and quadrupled in 1970 to 701. In 1971, it climbed to 1580, according to a 1972 Atlanta Constitution article that cited government data.

That was still far below the nearly 35,000 abortions in Georgia last year. But some public health officials estimated Georgia had two to five times as many illegal abortions as legal ones in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That didn’t include women who traveled to New York for legal abortions.

Atlanta-New York abortion flights

With Georgia’s new abortion law, women are again considering traveling to another state for the procedure, and some abortion rights groups are raising funds to help them. Many other states also have tightened restrictions in recent weeks, particularly in the South, narrowing options, although North Carolina and Florida’s laws remain less strict than Georgia’s.

Back then, there were even fewer options. Only four states legalized elective abortion procedures before 1971: New York, California, Alaska and Hawaii.

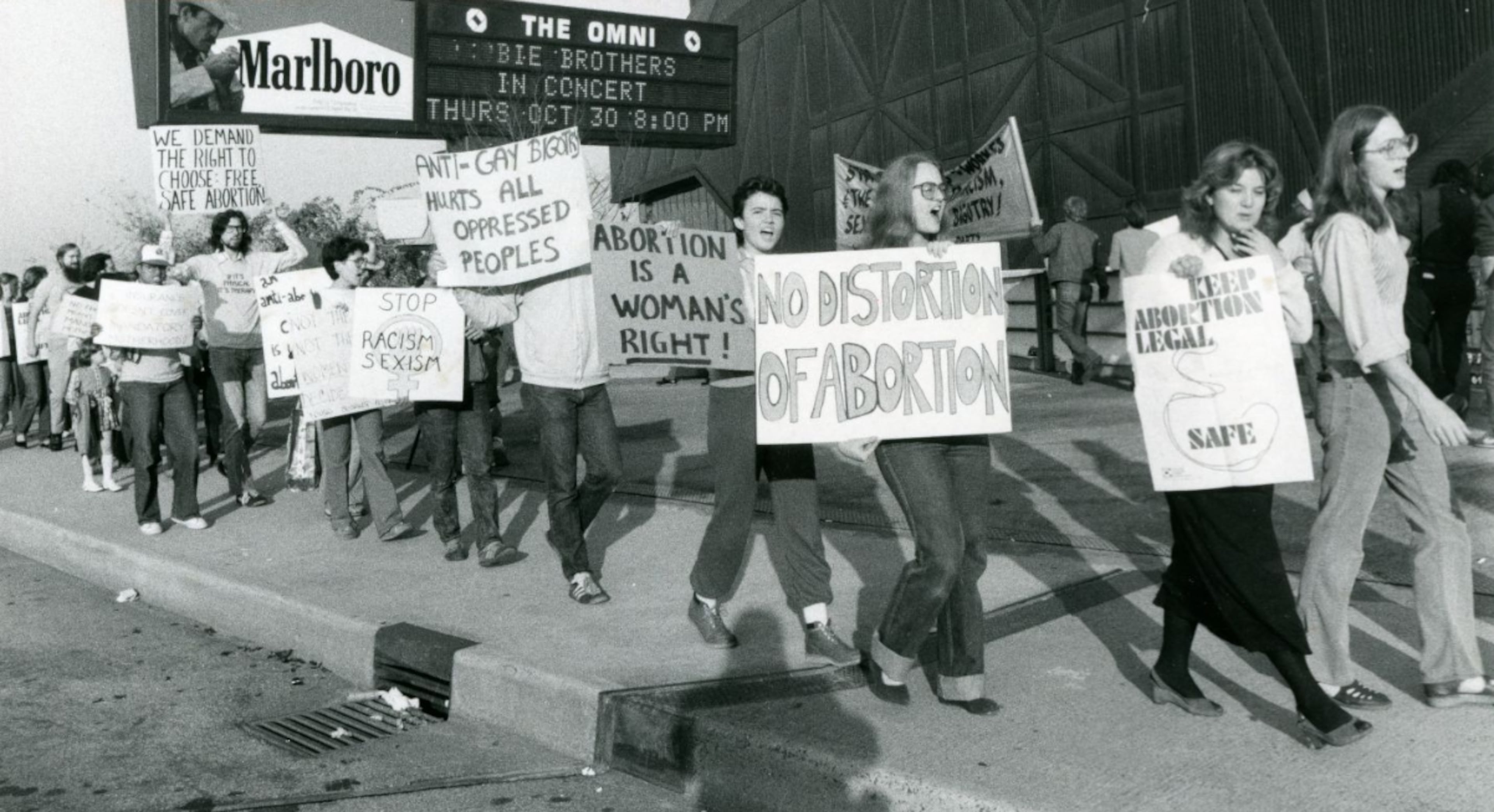

Advertisements for agencies that planned New York abortion trips littered college newspapers across Georgia. A group called Problem Pregnancy advertised, “Pregnant? Need Help? Problem pregnancy will provide totally confidential alternatives.”

Problem Pregnancy scheduled groups of women to travel together to New York from Atlanta six days a week, according to an Atlanta Constitution article in 1972. The round-trip cost, including the flight, the procedure and transportation from the airport, was roughly $300, or nearly $3,000 in today’s dollars.

In 1970, the number of Georgia women obtaining abortions out of state exceeded in-state abortions by three times, Dr. Carl Tyler, then-chief of the CDC’s Family Planning Evaluation Branch, said in a 1972 Atlanta Constitution article.

In the first two years after New York’s liberalization law was passed in 1970, health officials estimated that more than 400,000 abortions were performed in that state. Women from outside of New York accounted for nearly two-thirds of those procedures, according to a 2018 New York Times article.

In pre-Roe Georgia, Lysol and coat hangers

Since the late 1970s, emergency birth control options such as the “morning after” pill have become increasingly widespread. In 1972, for women who could not afford a trip to New York, often the only alternative was to seek an illegal abortion.

Some women nicked their uteruses and bled so much that doctors were forced to intervene, according to Judith Taylor, a reproductive rights activist whose mother-in-law founded the first Planned Parenthood in Georgia. Others drank poison or douched their vaginas with Lysol after sex, historians said. Some used coat hangers to puncture their uteruses and rip their abdominal cavities, according to Atlanta Journal articles from the time.

“I’ve seen the results of women who had bad abortion procedures,” Mary Long, an emergency room nurse at Grady during the 1960s, said in a 1999 Georgia State University women’s history project interview. “They would come in lifeless … almost near death.”

One unmarried 18-year-old woman told The Atlanta Constitution in 1972 about an illegal abortion she had in a woman’s apartment. “I feel I was one of the lucky ones to live through it,” she said at the time.

Illegal abortions killed 93 Georgia women between 1960 and 1971, Dr. Bob Hatcher, a family planning expert, wrote in a 1972 Atlanta Constitution article. But that was likely a small fraction of the true number, says McGee. Such abortions were carried out in secret and often would only come to light if a woman sought medical care afterward.

Back then, birth control was expanding, but still severely limited in Georgia. Only married women with private doctors could access the pill and the IUD, which were introduced in the 1960s. In 1962, Grady Memorial Hospital opened a birth control clinic, the only place in Georgia where a woman too poor to see a private doctor could obtain birth control. Georgia’s public health clinics declined to distribute the pill, and instead promoted abstinence and distributed contraceptive foams.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, women in Georgia gave birth to roughly three children. Last year, the state’s fertility rate was two children per woman.

Abortion and race

One thing that hasn’t changed over the last half century in Georgia, though, is racial disparities in maternal mortality.

Of 205 non-hospital abortion deaths analyzed in Georgia from 1950 to 1969, 69% were Black women, according to the 1971 CDC study. Between 1965 and 1969, Black women had a maternal mortality rate from abortion that was 14 times greater than their white counterparts.

Abortion mortality was “increasingly a Black health problem,” the CDC study concluded at the time. It attributed this disproportionate impact on Black women to their lower socioeconomic status.

Between 1965 and 1969, the overall maternal mortality rate among Black women in Georgia was 3.6 times higher than white women for live births, according to the same study.

In 2019, nearly two-thirds of those who received legal abortions in Georgia were Black, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

But a bipartisan state panel report in 2019 estimated Black mothers were three to four times more likely to die in the year after childbirth than their white counterparts, amid continued disparities in overall access to health care.

Rochat, the Emory professor who helped author the 1971 CDC study, fears the disparities could widen even more now that most abortions are illegal again in Georgia.

“The biggest challenge, then and now, will be for those of lower socioeconomic status,” because such women have fewer health care options and less financial flexibility, he says.

Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade

Ruling means states can ban abortion

When is abortion legal under new Georgia law?

AJC Podcast: What you need to know about Georgia’s anti-abortion law

Abortion clinics scramble as Georgia’s restrictive new law takes hold

Georgia not alone: Neighboring states tighten abortion restrictions

What are the abortion laws in other states?

With 2022 election hanging in balance, Georgia abortion limits take effect

District attorneys react: Metro Atlanta DAs say they won’t prosecute women under Georgia law