Responding to a call from a Centerville personal care home, EMS finds a resident with Alzheimer’s living in squalor and soaked in urine. Staff members could not recall the last time the resident got a bath.

In videos uploaded to Snapchat, a caregiver at an Athens assisted living facility berates and torments a resident. In one video, the staffer lies and says the resident is in jail for murdering their spouse. Another video shows a different resident screaming when the staffer enters the room.

EMS is called after a worker at another senior care facility accidentally administers 24 units of insulin instead of two, causing the resident’s blood sugar to drop alarmingly low. The error is never properly documented, and the home had no records that the staffer was properly certified as a medication aide, an inspection reveals.

Staff members at a North Georgia facility tell state inspectors they found a resident in a sexual position, sobbing and blaming another resident for sexual assault. The abuse was never reported to law enforcement or the state. The family was not alerted, either, the inspection finds.

A memory care facility with no security cameras didn’t realize a resident was missing for a second time until a bystander called saying they saw someone in pajamas and using a walker going down a main street.

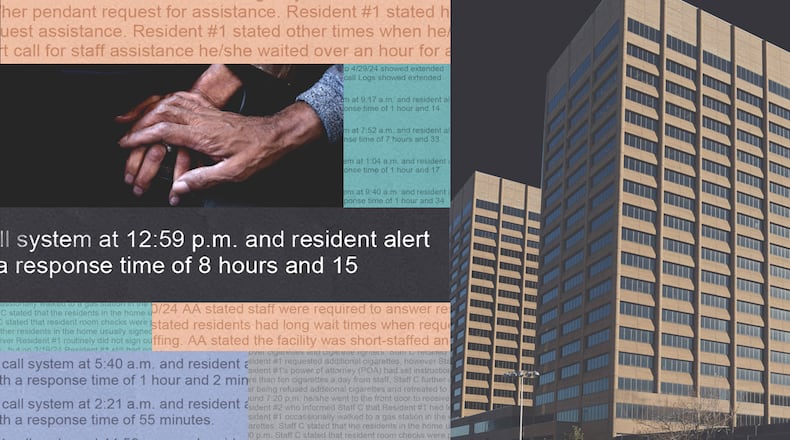

It took as long as eight hours for staff at a Gwinnett assisted living community to respond to emergency alert calls from a resident who was blind and used a wheelchair and needed help to dress, bathe and toilet.

At a Stockbridge senior home, inspectors in July find no air conditioning and no fans, leaving residents in sweltering rooms. Staff members tell inspectors that the air conditioning had been an issue for three years.

The Georgia Department of Community Health investigated each of these incidents this year. They were documented, detailed and broken down by state surveyors and ultimately deemed to be the result of “D-level violations” of state regulations — the lowest possible infraction level, which comes with zero financial penalties. A flick on the wrist.

And this is the norm.

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Community Health

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Community Health

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation has found that over a recent 12-month period, more than 90% of violations found at assisted living and large personal care homes were given D rankings. While the statistic might imply Georgia’s senior sector is operating at the highest-possible level with very few serious incidents, the details behind these rankings tell a different story.

Reviewing hundreds of state inspection reports, the AJC found D’s being doled out in cases in which residents were severely injured, where inspectors found a dozen or more violations at a home in a single inspection, and when homes continued to exhibit the same problematic practices over multiple inspections. The vast majority of the inspections resulted from complaints rather than routine inspections, raising additional questions about may occur in homes when the state is not flagged to an issue.

On the rare occasion the state deemed violations as more serious than a D, inspection reports provided little clarity as to what triggered them — as similar incidents at other homes could be met with vastly different violation scores.

Reviewing court documents, the AJC also found that if facilities contested their higher-level penalties and fines, the state was almost always willing to enter into a settlement agreement. These contracts could cushion fines by not only giving facilities more time to pay, but also by significantly reducing the actual penalty.

In one notable case, a facility was fined just over $6,000 for nine violations tied to an incident in which a resident with dementia wandered away from a facility and died after being hit by a car. After a settlement agreement, the state reduced the fine to $3,000, to be paid off over a year. In other words, the facility owed $250 a month — significantly less than what a resident pays to live in and be cared for by the home.

The findings raise questions about the state’s commitment — as well as its ability— to hold accountable the nearly 1,700 assisted living and personal care facilities it licenses. The findings also underscore failures to live up to the promise of change.

In 2020, following an AJC investigation that documented abuse and neglect across the private-pay senior care industry, state lawmakers passed reform legislation promising much-needed protections for elderly people living in assisted living and personal care homes. As part of the new law, which took effect in July 2021, the state increased home staffing requirements, as well as fines.

That legislation gave Georgia the reputation of having some of the nation’s toughest rules. In 2023, for example, the Washington Post released a state-by-state breakdown of assisted living regulations, ranking Georgia as having some of the most robust.

And the Georgia Senior Living Association, an industry trade group that represents homes and has pushed to relax staffing requirements enacted through the 2020 reforms, said in a written statement that it believes the regulatory environment is fair and that the majority of senior home residents are highly satisfied with their care.

But regulations are only as good as enforcement. DCH’s blunted response that the AJC’s investigation found gives little incentive for homes to rectify problems. That poses a serious concern in a state where by 2030 nearly a fifth of the population will be 60 or older.

DCH declined the AJC’s request for an interview with Commissioner Russel Carlson, agreeing only to answer questions in writing.

Asked about the reasoning behind several of the D ratings in which violations put residents in serious danger, DCH would only point to its enforcement rubric, which the agency refers to as the “matrix.”

“Any questions regarding the severity levels of infractions we would refer you to the Matrix, as those decision are based on the facts of each individual case and dictated by the Matrix,” Fiona Roberts, a spokesperson with DCH, wrote.

“Each individual complaint investigation/compliance review considers all facts and variables that contributed to an outcome which may impact the writing of a deficiency as well as the severity level,” she continued, copy-pasting the same reply to each question.

The only matrix the AJC was able to find on the state’s website was outdated. To receive the current matrix with the higher fines, the AJC had to request it.

“This is very bad,” said Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, which advocates for people in senior care facilities. He likened the assisted living sector to the “Wild West” because it lacks the oversight found in federally regulated nursing homes. This comes despite the fact they are increasingly caring for the same populations.

“I see a domino effect. You have the state not doing a good job overseeing the operators and then the operators not doing a good job. There’s such a gap between what these homes market and say they’re providing and the reality,” he said.

So much is underreported and under-enforced at these state-regulated homes that the public doesn’t have a way to evaluate them, he added.

“People see this promise of assisted living, and because so much of it flies under the radar, there is very little cracking that shell.”

The reforms

Assisted living and personal care homes like to market themselves as “social facilities” and showcase amenities like walking trails and restaurant-style dining. However, although some of their residents may just want help with meals, housekeeping or taking medicine, many need extra care as they are fragile or deal with dementia.

Residents described in the inspection reports reviewed by the AJC, for example, had a litany of health complications including Parkinson’s, congestive heart failure, diabetes, Alzheimer’s and repeated falls.

The mismatch between the branding and the care actually required by residents was at the heart of the AJC’s 2019 investigation, which revealed dangerous gaps that left the vulnerable at risk. That series of stories found few consequences from DCH when seniors were harmed, with fines too low and the inspection staff too thin to protect residents.

The stories were met with immediate outrage and within a year there was near-unanimous approval for House Bill 987, a reform package that promised to raise standards and take seriously instances that left residents in harm’s way.

“This bill addresses an urgent need, that was brought to my attention, to dramatically reform our standards for elder care in Georgia,” Sen. Sharon Cooper, R-Marietta, who introduced the legislation, said at the time of its passage.

Under the reforms, administrators must pass a test to be licensed. Memory care units have to be certified. Nurses are required in assisted living and memory care, and overall staffing and training requirements increased.

To enforce those rules, fines increased.

Financial penalties had tapped out at about $601 for violations that caused death or serious harm. The new law required the state to impose fines of at least $5,000 for infractions that caused a resident to be suffer serious physical harm or to die. It also increased maximum fines to up to $2,000 per day for each violation.

At the crux of the state’s reform is the updated rubric for evaluating violations, which categorizes violations based on the harm or potential harm to residents.

But violation categories are vague, and the matrix provides little explanation of how the violation level is determined.

Category I violations, for example, “cause death or serious physical or emotional harm or pose an imminent and serious threat to the physical and emotional health and safety of one or more persons in the care.” And Category II violations have “direct and adverse effect on the physical or emotional health and safety of one or more persons in care.” Once death has been ruled off the table, the difference between these two explanations is not clear. Imminent and serious threat is not defined, nor is direct and adverse effect.

Category III violations are described as “indirectly or over a period of time has or is likely to have an adverse effect on the physical or emotional health and safety of one or more persons in care” and also include the violation of administrative and reporting requirements.

Inspection reports reviewed by the AJC show that sexual assaults, incidents of residents wandering away, filthy living conditions and inadequate food were all deemed by the state to be “indirect harm.” This is largely because while the matrix emphasizes the physical and emotional harm felt by residents, state inspections only concern the specific rules violated.

In January, for example, the AJC wrote about a 78-year-old with dementia who was left on the floor of a memory care unit for six hours as he begged and clawed to get back into bed. He died the next day. The incident at Savannah Court of Lake Oconee was reported to DCH by the man’s daughter, who was able to view the entire episode via a Ring camera. The subsequent incident report confirmed the sequence of events but ultimately focused squarely on the rule violations — such as the fact that three of the staffers watching her dad that night had no competency-based memory care training, as is required by state law. And so despite the family’s shock and despair, the state categorized the event as a sequence of D-level violations.

While the new state rules also indicate that facilities should get increasingly higher rankings for repeat violations, the AJC found this wasn’t always the case.

Griffin House South, a personal care home in Claxton, received 12 D’s for an inspection completed in March. Most of the D’s stemmed from issues of cleanliness and a lack of adequate and healthy food options. A review of previous reports shows the facility received three D’s in 2022 for issues involving cleanliness and food, and two D’s in 2021 for failing to maintain the residence.

“It is what it is, as far as the tags,” said Jill Griffin, who opened the facility in 2006. While she didn’t dispute the violations, she felt the reports didn’t give the full picture of the care provided.

“I will say we have had lots and lots of families that have been well taken care of,” she said.

Griffin sold the facility last month after struggling with operating a small business serving a vulnerable population with complex needs and being examined by inspectors who she said didn’t always have the appropriate nursing background.

The state has also sidestepped the rule calling for higher violation tags for repeat infractions by citing slightly different regulations for similar incidents. Dahlonega Assisted Living, for example, had issues maintaining records of controlled substances in 2023 and 2024, and both times this warranted Ds because the state categorized the events as slightly different transgressions.

The Dahlonega home told the AJC it has since corrected the violations.

While DCH did not answer questions about how it ranks violations, at a hearing attended by a reporter this past winter a surveyor explained that those who inspect the homes give initial ranking suggestions and then managers, who do not visit the facility, give the final letter grade.

“There are certain violations that automatically warrant a Category I, and as a surveyor we can put it there, but it’s ultimately up to management once it goes through the review process to make that determination,” said Georgina Bowen, a state compliance specialist who performs inspections.

Easy appeals

In the rare scenario where a facility gets dinged with an infraction higher than a D and must pay a fine, it has two choices: Pay or contest within 10 days by requesting a hearing before a state administrative law judge.

An AJC review of data surrounding this latter route highlights further opportunities for homes to avoid significant sanctions. DCH reached settlement agreements in nearly 65% of the cases that were completed in administrative courts between 2003 and July 2024.

Often, these include monthly payment plans for the fines, which can help cushion the impact. They can also come with fine reductions.

Credit: TNS

Credit: TNS

Consider a court case involving Greenwood Place Retirement Community, a 49-bed assisted living facility in Wrightsville.

On the morning of July 11, 2020, just 10 days after Gov. Brian Kemp signed the much-celebrated reform bill, a resident was found “covered head to toe in ants.”

According to DCH’s subsequent inspection report, ants were on the resident’s face, neck, clothes and bedsheets. They were coming out of his ears. Blood covered his face — likely, the report noted, from the resident scratching the ants off. When staff went to clean him up, they discovered his incontinence briefs were full of urine, indicating he hadn’t received incontinent care overnight, despite facility rules requiring check-ins every two hours. The home didn’t call the family after the discovery; instead, a staff member sent texts, according to the report.

The resident, who was moved to a hospice, died a week later, according to the state’s report. It doesn’t note the cause of death.

In September DCH completed its investigation and sent a letter with its findings: Two Category I violations for failure to maintain pest control and failure to support resident’s rights. Greenwood would be fined $2,402.

It requested a hearing to contest the penalty, and in April 2021 a settlement agreement was signed. The amount was dropped to $1,201.

When asked why it decided to reduce the fine, Roberts, the DCH spokesperson, said the department does not discuss legal matters related to specific cases.

“As far as general settlement agreements or negotiations, legal/DCH has the authority to reduce, settle, negotiate any fine amount, and many factors are included in these decisions,” she wrote in an email, adding that settlement agreements may contain certain requirements, such as directed plans of correction that, she wrote, “dictate actions that lead (to) improvement in compliance with requirements.”

A copy of the Greenwood settlement agreement, reviewed by the AJC, does not include mention of a plan of correction.

Greenwood Place Retirement didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“This just raises my blood pressure, probably 100 points, because we run into this all the time,” said Melanie McNeil, Georgia’s long-term care ombudsman.

She and advocates have few answers as to why the department’s Healthcare Facility Regulation Division operates the way it does.

“We complain to the department, and they sometimes take action. A lot of times they don’t,” said McNeil, later adding: “We don’t usually count on facilities to be fined or otherwise sanctioned by HFR. That’s not the way things get done.”

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Community Health

Credit: Ga. Dept. of Community Health

An uphill battle

No case may better highlight the blunted approach to accountability by both DCH and the administrative courts as Savannah Court of Lake Oconee, a 72-bed personal care home in Greensboro.

In August 2023 the state moved to shut down the home, but then backtracked to engage in settlement talks instead. An AJC investigation published last January found that this would have been the third settlement agreement the state was entertaining for the home, which had accrued over 70 violations since 2021, including infractions involving the deaths of two residents and a sexual assault that occurred when these resolution talks were underway.

The state then scrapped the discussions and moved to close the facility.

Yet, ultimately, the court sided with Savannah Court.

The decision, written by Administrative Law Judge Charles Beaudrot, found that DCH could fine the facility for the latest violations but lacked grounds to revoke its permit.

Last month, the home was sold and rebranded Haven of Lake Oconee. DCH has yet to post an inspection since it was sold.

Mollot, with the Long Term Care Community Coalition, said the case shows how difficult it is to hold operators accountable.

“DCH has demonstrated a lack of urgency when cracking down on assisted living, even when there are allegations of horrific abuse of vulnerable residents. And even when things get so bad that the department takes meaningful action, it faces an uphill battle in the courts exercising its regulatory authority,” he said.

The end result, Mollot said, is a system where assisted living and personal care home operators, many of whom are for-profit entities, run the show. DCH has too few inspectors, still, to even keep up with hundreds of homes and volume of complaints.

“They know that there is little chance that they will be penalized when they fail to keep their promise to seniors and their families,” he said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured