In a real-life saga with plot twists straight out of Hollywood, federal authorities believe a man locked away in a Georgia prison stole $11 million from a billionaire movie mogul — and may have gotten away with stealing millions more from other billionaires.

The story involves gold coins, a private plane, duffel bags stuffed with cash and a Buckhead mansion.

And it adds up to potentially one of the biggest heists ever pulled off from inside an American prison – made even more startling by the fact that the inmate was in the Georgia Department of Corrections’ Special Management Unit, a maximum security facility designed to house the state’s most hardened criminals.

For more than two years, federal agents and attorneys have been sifting through evidence they believe points to how 31-year-old Arthur Lee Cofield Jr. assumed the identity of California billionaire Sidney Kimmel and stole $11 million from Kimmel’s Charles Schwab account.

Kimmel is the chairman and CEO of Sidney Kimmel Entertainment, the Los Angeles-based company responsible for such films as “Hell or High Water,” “Crazy Rich Asians” and “Moneyball.”

Federal authorities believe Cofield, using contraband cell phones, convinced customer service representatives at Charles Schwab that he was Kimmel and arranged for $11 million to be wired to a company in Idaho for the purchase of 6,106 American Eagle one-ounce gold coins.

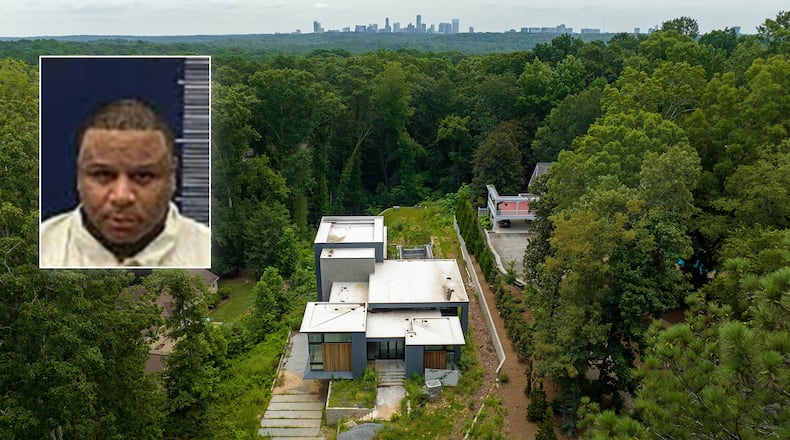

Cofield then allegedly arranged for a private plane to transport the coins to Atlanta, where some were used to buy a $4.4 million house in Buckhead.

“Cofield was a shrewd, intelligent individual who could con you out of millions,” said Jose Morales, who was the warden at the Special Management Unit when Cofield was there.

Cofield has pleaded not guilty to charges of conspiracy to commit bank fraud and money laundering. Two others, 65-year-old Eldridge Bennett and his 27-year-old daughter, Eliayah Bennett, have also pleaded not guilty to charges that they worked on the outside to further the scheme.

Little has been reported about the case since federal authorities first uncovered it in 2020. But recent court filings and other documents reviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reveal significant new details, including the fact that Kimmel was the victim and that he may not be the only one.

Beyond the cinematic aspect, the case provides yet another stark example of the Department of Corrections’ failure to curb illegal activities.

“Cofield was a shrewd, intelligent individual who could con you out of millions."

Long before federal authorities got involved, GDC officials knew that Cofield, a documented gang member serving a 14-year sentence for armed robbery, had the ability to get his hands on contraband cell phones and use them for criminal activity.

In fact, Cofield was moved from Georgia State Prison to the Special Management Unit after a warrant for his arrest was issued in Fulton County for ordering a shooting in Atlanta. He still faces charges including attempted murder for that crime, which left the victim paralyzed from the waist down.

Cofield was released from GDC custody in October 2021 after completing his sentence for armed robbery and was placed in federal custody, where he remains. Steven Sadow, an attorney representing Cofield in both the federal and Fulton County cases, declined to make him available for an interview or comment on either of those cases himself.

Targeting billionaires

Nothing in the court filings reveal how Cofield may have come to target Kimmel, although it appears the movie maker wasn’t the only billionaire in the inmate’s sights.

Kimmel, 94, is worth $1.5 billion, according to Forbes. Totally self-made, he founded the apparel company Jones New York, eventually selling it for $2.2 billion. He now focuses on filmmaking and philanthropy. The cancer center at Johns Hopkins University bears his name, as does the medical school at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Credit: Eric Charbonneau/Invision/AP

Credit: Eric Charbonneau/Invision/AP

Matthew Kamens, an attorney who serves as an adviser to Kimmel, wrote in an email to the AJC that if in fact there was fraud, the victim was the Charles Schwab Corporation, not Kimmel. “Mr. Kimmel was unaffected by whatever occurred, and we have no knowledge of what occurred, either in terms of background or context,” Kamens wrote.

In a statement for the AJC, Schwab said it fully reimbursed Kimmel — per company policy for cases of unauthorized activity — and alerted authorities that the account had been compromised. “As soon as Schwab was aware of suspected fraudulent activity, we launched an investigation, initiated measures to protect the client’s account and notified the authorities,” the statement says.

The company, citing the fact that the case remains unresolved, declined to go into greater detail.

Credit: Danny Robbins

Credit: Danny Robbins

Although federal authorities have only charged Cofield with scamming Kimmel, they believe it’s likely he stole millions in a similar fashion from other billionaires as well.

“Mr. Cofield has figured out a way to access accounts belonging to high net worth individuals, frankly billionaires, located across the country,” a federal prosecutor, Scott McAfee, said at a bond hearing in December 2020.

At the hearing, McAfee said the government also had evidence that Cofield accessed an account belonging to Nicole Wertheim, the wife of Florida billionaire Herbert Wertheim, and stole $2.25 million, turning those funds into gold coins as well.

No criminal charges have been filed in that case, and Wertheim, an optometrist whose innovations with eyeglass lenses have led to wealth estimated at $4 billion, did not respond to messages from the AJC.

Bob Page, the spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the Northern District of Georgia, said the ongoing nature of the case prevents prosecutors from discussing it publicly.

Hundreds of phones

There can be little doubt about how Cofield was able to maintain a presence in the outside world. Twelve times at five different Georgia prisons, he was found to possess contraband cell phones, incident reports show.

Officers conducting a shakedown at Georgia State Prison in 2016 found a Verizon LG touch screen cell phone and charger concealed in Cofield’s groin area. Asked to provide a written statement, he refused, saying, “I don’t give a (expletive) about that phone, I’ve had hundreds of phones,” the report says.

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Morales said he suspected Cofield was paying off correctional officers for the phones but could never prove it.

“He was so good at it that we were never able to ascertain how he got them in there,” Morales said.

Longtime corrections official Anthony Schembri, formerly New York City corrections commissioner and secretary of the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, said Cofield’s ability to repeatedly acquire cell phones must be viewed as a reflection on GDC management.

“They know what he’s doing with cell phones and he’s still getting them in? What does that tell you?” he said.

Schembri said he could not recall a scam of similar magnitude from within a U.S. prison. If the feds are successful with their prosecution, “this should be a training example for correctional systems across the country,” he said.

GDC spokesperson Joan Heath did not respond directly to questions about Cofield. Instead, she noted that the GDC, like other prison systems, fights a “daily battle” against contraband cell phones, particularly the use of drones and other creative methods to get phones to inmates. Stopping inmates from using cell phones to carry out crimes is a job the agency takes “very seriously,” she added.

His own gang

The crimes that first sent Cofield to prison show him to be far from the polished criminal the federal government now claims him to be. He stole $2,600 from a branch of First Choice Community Bank in Douglasville and apparently was so inept that the money had a dye pack that exploded moments after he left the bank.

He had just turned 16 when he was sentenced.

Prison, however, brought stature. Inside the GDC, he formed his own gang, known as Yap, short for young and paid. As its leader, he was Yap Lavish, and, according to numerous accounts, he lived up to the name.

“They know what he's doing with cell phones and he's still getting them in? What does that tell you?"

Much of his attention at the time was on a young Atlanta woman, Selena Holmes, with whom he had developed a phone relationship. Cofield arranged for Holmes to have thousands of dollars in cash, a Mercedes and an apartment in a Buckhead high rise even though they’d never met, according to statements made in court by Rickey Richardson, an attorney who represented Holmes.

“He apparently, through the gift of gab and persuasion — darkness, I don’t know — was able to produce lots and lots of money,” Richardson said.

As part of the arrangement, Cofield would watch Holmes, who became known as Yap Missus, having sex on FaceTime, Richardson said.

When Cofield thought Holmes had become romantically involved with a man in Atlanta, Fulton prosecutors allege, he ordered two gang associates to kill the man, 36-year-old Antoris Young. When the shooting went down, Cofield was on his phone from prison confirming that it happened, one of the prosecutors, Cara Convery, said in court.

Holmes, accused of locating the victim on the day of the shooting, remains the only person convicted in that case. She pleaded guilty to participation in criminal street gang activity and other charges in June 2021 but did not agree to testify against Cofield. She’s now serving a15-year prison sentence.

Inside the SMU

The Special Management Unit, commonly known as the SMU, is part of the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Prison in Butts County. It houses the department’s most problematic inmates in single-man cells with limited exercise and no communal meals.

Against that backdrop, the government contends, Cofield’s scheme played out over three months in the summer of 2020, unraveling only after an analysis of a confiscated cell phone yielded evidence of his moves.

According to the government, Cofield called Schwab as Kimmel to open a new checking account using TextNow, an app that made it appear as if he was calling from a Los Angeles area code. Told he needed a form of ID and a utility bill, he came up with a photo of Kimmel’s driver’s license and a copy of his Los Angeles water bill.

Again posing as Kimmel, authorities allege, Cofield contacted an Idaho company that deals in precious metals, Money Metals Exchange, to arrange for the purchase of the gold coins. To wire the money, he provided Schwab with a disbursement request along with a forged letter of authorization from Kimmel, authorities contend.

“[Cofield] apparently, through the gift of gab and persuasion — darkness, I don't know — was able to produce lots and lots of money."

Then, the government says, he arranged for a security detail and a private plane to get the coins to Atlanta. Authorities believe Eldridge Bennett met the plane at Atlanta Signature Airport to collect the loot.

Around that time, according to authorities, Eliayah Bennett began looking for houses in Buckhead and found one she liked on Randall Mill Road.

The house, which sits on 1.4 acres, was still under construction and wasn’t for sale. However, the owner, Michael Zembillas, agreed to sell after Cofield, said to be Eliayah Bennett’s husband and using the name “Archie Lee,” called and offered $4.4 million.

The government says Zembillas received the majority of the down payment, some $500,000, in cash. At the closing, more cash was delivered, carried into a branch of Cadence Bank in Alpharetta in duffel bags by the elder Bennett, authorities claim.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Where’s the gold?

The house on Randall Mill is now subject to forfeiture and sale by the government. As for the rest of the gold, federal agents conducted a search of the house in December 2020, focusing on a built-in safe, but apparently did not find it there.

Several people who dealt with Cofield as “Archie” now look back and wonder how they were taken in.

“The whole thing was weird,” said Scott West, the architect who designed the house and spoke to Cofield as “Archie” on several occasions. “He’d disappear for a couple of weeks, then call me and say, `Sorry, I was in Mexico,’ blah, blah, blah.”

Zembillas said “Archie " told him he worked as a scout for up and coming rap artists, a role that required having large amounts of cash on hand, and that he’d made money by investing in Bitcoin.

When Zembillas learned from an agent with the U.S. Postal Inspection Service who “Archie” really was, he said the first thing he considered was Cofield’s criminal history.

He wondered if that was something he had to worry about. Then he started thinking about the situation as a whole.

“Yeah, there were a lot of things that crossed my mind,” he said. “Like, how did he do this with a cell phone?”

Contact investigative reporter Danny Robbins by email at AJCInvestigations@ajc.com

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured