Three days before his 90th birthday, Jimmy Carter was the guest of honor at a surprise party thrown by the residents of tiny Plains, Ga. He seemed genuinely moved that over 200 people had turned out at a park on a busy fall afternoon — and slightly chagrined not to instantly recognize every single face in the crowd. So he planted himself in a spot on the way to the ice cream table and announced that anyone who wanted a cool treat had to get by him first, either by shaking his hand or sharing a hug.

It was classic Jimmy Carter, and not just because it took place in his beloved hometown. In one move, it perfectly encapsulated the life of the man who’d determinedly staked out his unique place in history:

His greatest accomplishment wasn’t being president of the United States. It was what he did afterward.

“People will be celebrating Jimmy Carter for hundreds of years,” said Rice University history professor Douglas Brinkley, the author of “The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter.” “His reputation is only going to grow.”

Carter, the only Georgian ever elected to the White House, died Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024. He was 100. Carter, who lived longer than any other U.S. president, entered home hospice care in Plains, Georgia in February 2023 after a series of short hospital stays.

He will be buried outside the modest ranch house in Plains where he returned to live after losing his 1980 re-election bid, and where, just down the road in his former high school, a replica of his Nobel Peace Prize is displayed. He will lie next to Rosalynn Carter, his wife of 77 years, who died in November 2023.

Credit: AP file and AJC file

Awarded in 2002 “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts,” the Nobel seemed to officially confirm Carter’s longtime unofficial title as America’s greatest ex-president. Ironically, he’d always quietly chafed at that distinction, feeling it gave short shrift to his accomplishments in the Oval Office.

In fact, history has been somewhat kinder to Carter’s presidency than the prevailing image of him at the time he lost all but six states to Ronald Reagan: that of a morally rigid outsider who was in over his head in Washington and unable to free 52 hostages taken from the U.S. Embassy in Iran for over a year.

Now, he’s as likely to be remembered for forging the Camp David Accords, which set the table for a historic peace treaty in 1979 between Israel and Egypt that still holds today. And for never plunging the country into war, a fact that Carter, a Naval Academy graduate, stressed increasingly in his later years as the U.S. struggled to disentangle itself from costly conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Still, it was his post-White House years that ultimately came to define him. Eschewing the usual presidential retirement plan of ghosted memoir writing and high-priced speechmaking, Carter instead swung hammers for Habitat for Humanity and battled Africa’s debilitating Guinea worm disease before most Americans knew either one existed.

He traveled to the Congo, Haiti, Libya and numerous other far-flung tinderboxes to monitor elections for fairness.

He wrote 32 books, won a Grammy and regularly returned home to teach Sunday school at little Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains.

He turned a serious cancer diagnosis at age 90 into one last high-profile campaign that offered hope and help to millions of others confronting the possibility of their own mortality.

He utterly transformed our idea of what a former president could and should be.

And he did it mostly by refusing to apologize for who he’d been all along.

“After he lost so resoundingly, he could’ve said, ‘OK, they didn’t like me, so if I’m still going to be a national and global figure, I’m going to have to change my personality,’” University of Georgia history professor James C. Cobb said. “He didn’t do it. He never got to the point of trying to act like he wasn’t a small-town Southern boy at heart.”

II. Rural roots, hometown values

Credit: Jimmy Carter Library

Carter’s journey to prominence began in the flatlands of southwest Georgia, where his family had lived for generations.

He was born in Plains on Oct. 1, 1924, the first of four children of Earl Carter, a farmer and businessman, and Lillian Gordy Carter, a registered nurse. When Jimmy was 4, the Carters moved 2 1/2 miles away to a 360-acre farm in the tiny community of Archery.

The family home sat on a dirt road and had no electricity or indoor plumbing for years. Earl Carter farmed cotton and corn and was one of the first locals to grow peanuts. The future president worked in the fields alongside Black tenant farmers and their children, who became his best friends.

Some three-quarters of a century later, Jimmy Carter suggested he’d absorbed Archery’s lessons like the hot south Georgia sun.

“I’d say my total commitment to human rights came from my experiences living among African-American families and seeing the ravages of segregation,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2014.

His feet may have been firmly planted in the earth of the South, but even at a young age, his mind roamed widely. He read “War and Peace” at age 12 and pored over picture postcards that his favorite uncle, a Navy man, sent from exotic ports of call. He fixed on the idea of attending the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, some 800 miles away. After a year at Georgia Southwestern College in Americus and another at Georgia Tech, he finally got there. Carter graduated in 1946 and returned to Plains just long enough to marry Rosalynn Smith, his sister Ruth’s best friend, before embarking on his own Navy career.

Over the next seven years, the couple moved repeatedly as Carter worked his way up the ranks. They had three sons — Jack, Chip and Jeff — each born in a different state. When Carter was chosen to serve in the Navy’s budding nuclear submarine program, it clearly marked him as a fast riser; but he gave it all up in 1953 when his father became terminally ill with cancer.

While home on leave, he later wrote, he was struck by the number and diversity of sickbed visitors whose lives Earl Carter had directly touched. He yearned to have a similar impact on people. He decided to resign his commission and come home to run the family’s peanut warehouse and farming operations, and to re-embed himself in the community.

Only then did he tell Rosalynn.

Credit: Chicago Sun-Times

“I was so mad I wouldn’t speak to Jimmy,” she recalled about the long drive back to Plains from upstate New York, site of their last Navy posting. “I’d say, ‘Jack, tell your daddy I need to go to the bathroom.’”

Despite that, they became a formidable team back in Georgia: He built the warehouse into a profitable business, she learned accounting and kept the books. He decided to run for governor, she packed the kids in the car and campaigned across the state.

Carter had already held numerous community positions — scoutmaster, Lions Club officer, member of the library, school and hospital boards — when he ran for a newly created position in the state Senate in 1962. He lost to a candidate backed by the political boss in neighboring Quitman County, then learned of possible voter fraud. Carter pleaded his case in court and in the media, and the results were overturned.

After serving two terms, Carter ran for governor in 1966 and finished third. Four years later, he scored an upset win over former Gov. Carl Sanders by portraying himself as a rural populist right off the peanut farm. He also subtly courted white voters, promising to invite Alabama’s well-known segregationist Gov. George Wallace to the Governor’s Mansion in Atlanta.

It was a sharp turn — if largely a pragmatic one — from Carter’s principled stand in 1958 when he was approached to join the White Citizens Council in Plains. He refused, and the family business lost customers.

A few months after his 1970 election as governor, he turned back again, even more sharply for the Deep South. His inaugural speech, which included the line, “I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over,” landed him on the cover of Time magazine.

Carter undertook a massive reorganization of state government, reducing the total number of agencies by two-thirds. His administration reshaped education and the mental health and criminal justice systems, and he appointed more women and minorities than all his predecessors put together.

Credit: Jimmy Carter Library

The state constitution limited governors to one term at the time, so Carter was ineligible to seek re-election. But, he had a backup plan.

During the 1972 presidential campaign, he’d invited Democratic contenders to stay in the Governor’s Mansion when in Georgia. He sized them up and concluded that if they were presidential timber, so was he.

Still, it came as a surprise when Carter called a group of intimates to Atlanta in 1974 and told them that he was going to run for the White House.

“We were speechless,” remembered Betty Pope, an old friend of the Carters’ from Americus. “One of us finally said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding, Jimmy.’”

But the country wasn’t laughing. The Watergate scandal and President Gerald Ford’s subsequent pardon of Richard Nixon had rubbed raw the American psyche. Voters were ready to give a Washington outsider a good look. Carter hit the trail months ahead of other Democratic hopefuls in 1975, offering a grin and a promise that he would never lie. He was the back-to-nature candidate, a peanut farmer with earth-tone green campaign signs.

Carter’s operation was just as authentically homegrown. Key advisers and staffers, such as Hamilton Jordan and Jody Powell, were Georgians. The Allman Brothers and other artists from Capricorn Records in Macon supplied crucial early funding. Pope and other friends in the “Peanut Brigade” charmed and disarmed Northern voters they canvassed with their warm Southern accents.

Credit: Associated Press

Early in 1976, Carter stunned the political world by finishing second to “uncommitted” in the Iowa caucuses and winning the New Hampshire primary. Next, he defeated Wallace in the Florida primary, a symbolic triumph of the New South over the past.

Soon, hundreds of media and thousands of visitors descended on Plains and its block-long downtown. Reporters found the Carter clan irresistibly colorful and quotable. Mother “Miss Lillian” had joined the Peace Corps at 68 and served in India. Brother and self-described redneck Billy sipped beer and served up witticisms at his service station.

By August, Carter was the Democratic nominee with a double-digit lead over Ford. The race tightened in the fall, and it was early on the morning after Election Day when Carter finally claimed victory by barely 2 percentage points. He’d won every Southern state but Virginia and scored heavy majorities among Black Americans.

For the first time since before the Civil War, the nation had elected a president from the Deep South.

III. White House Years

Credit: Associated Press

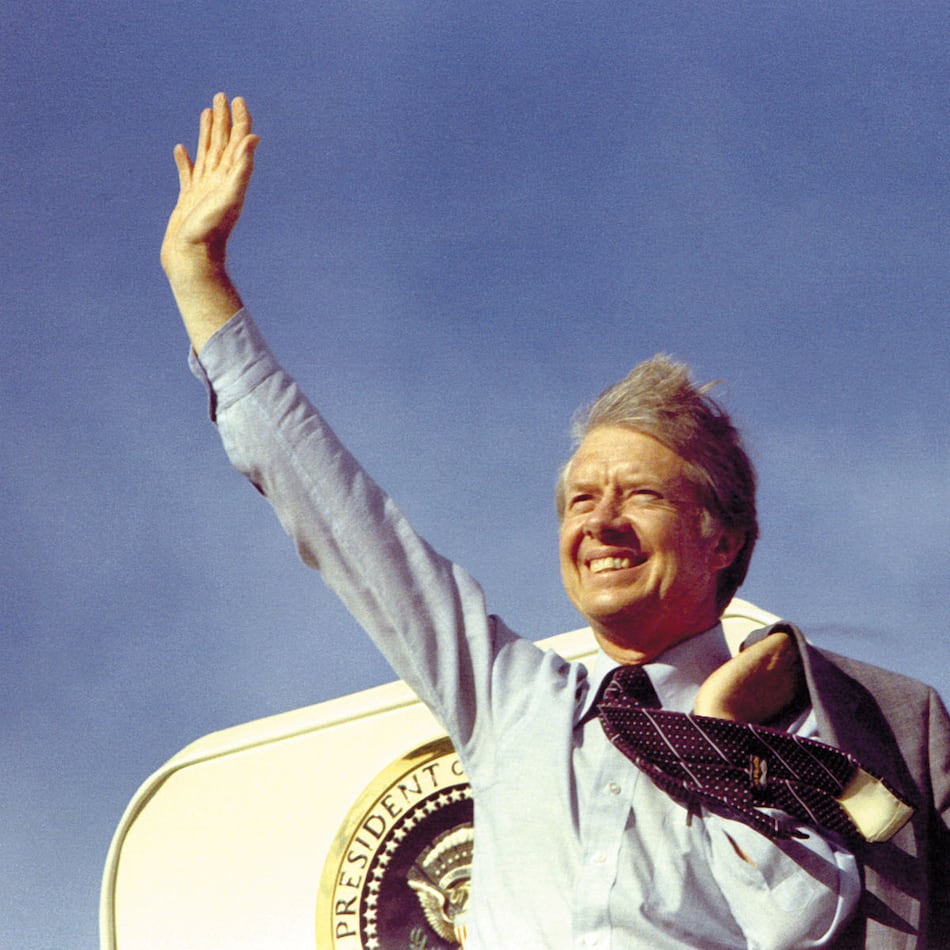

Once again, Jimmy Carter sprung an inaugural surprise. Previous presidents had always been driven along the parade route. But to the delight of millions watching in person and on TV, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter emerged from their limousine and walked down Pennsylvania Avenue, holding hands and waving.

The humble presidency had just begun. Carter carried his own bags, ordered the presidential yacht sold and enrolled 8-year-old daughter Amy in public school in Washington. He wore a cardigan sweater to go on TV and address the country about the need for a national energy policy that emphasized conservation.

Credit: Jimmy Carter Library

He backed up his words, creating the Department of Energy and cutting the country’s oil imports by half. On the international front, he normalized relations with China, signed the Panama Canal treaties and made human rights a cornerstone of U.S. foreign affairs.

In doing so, he reached back literally and figuratively to his place of birth. Human rights and civil rights had become intertwined in Carter’s mind from his earliest days in Archery; now, he prevailed upon Andrew Young to put his considerable skills and reputation to work spreading that message worldwide by becoming his administration’s ambassador to the United Nations.

Young, who’d moved to Atlanta in 1961 to become director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Citizenship School program and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.‘s top lieutenant, was then in his third term as a U.S. congressman representing Georgia’s 5th Congressional District. Years later, Young still recalled the compelling argument that persuaded him to give up the halls of the U.S. Capitol for the United Nations:

“I need someone who was with Martin Luther King in order for people to know that we are serious about human rights,” Carter told him.

But Carter’s most groundbreaking presidential achievement was the Camp David Accords, a high-stakes drama that played out in September 1978 with Carter as the world’s most determined stage manager. For 13 days, he played intermediary between Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, cajoling and praying with them in turns. At one point, he got down on the floor of his cabin at the presidential retreat, surrounded by maps and yellow writing pads, and sketched out a preliminary agreement. Begin and Sadat later won the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts.

Not everyone swooned for the small-town Southern boy approach, though. Washington insiders grumbled about the presence of so many newcomers from Georgia in the administration and even about the supposedly sparse food spreads at White House meetings. More serious was the increasingly defiant mood among congressional Democrats as their wish list of social programs was thwarted by Carter’s determination to pass a balanced budget.

The intraparty bickering finally burst into the open in ugly fashion when liberal icon U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy challenged Carter for the 1980 Democratic nomination. Carter ultimately prevailed, but by then, much of the country had come to view him as a bad combination of weakness and stubborn self-righteousness.

In November 1979, Iranian militants had stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and taken hostages. The roots of their anti-American hostility had been planted as far back as 1953, when the CIA had engineered the consolidation of power under Iran’s young king, Reza Shah Pahlavi. A growing revolutionary fever there at first forced the Shah to flee to Egypt in January 1979, and then finally broke the following fall when the White House somewhat reluctantly agreed to let him to come to the U.S. for cancer treatment. What was initially portrayed as a humanitarian gesture on Carter’s part was viewed much less charitably in Iran; the hostage crisis would come to dominate the final year of his presidency, playing out as a series of high-profile diplomatic efforts and embarrassments on the world stage while at home patriotic optimism gradually gave way to less familiar feelings of powerlessness and despair.

“This kind of symbolized for them that some bunch of students could seize American diplomatic officials and hold them prisoner and thumb their nose at the United States,” Carter adviser Peter Bourne later reflected on PBS’ “American Experience.”

Credit: Associated Press

Indeed, when ABC News began airing late-night updates on the hostage situation in November 1979, it titled the program “The Iran Crisis — America Held Hostage,” followed immediately by “Day (Insert Number Here).” The drumbeat of futility only grew louder when, on April 24, 1980, a secret mission to rescue the hostages went disastrously wrong. Code-named “Desert One,” it was ordered aborted by Carter when three helicopters malfunctioned and a fourth crashed into a transport plane, killing eight servicemen. Years later, the failed mission clearly still haunted the one-time commander in chief. During the remarkable press conference he held in August 2015 to discuss his cancer diagnosis and reflect back on his life and plans going forward, Carter was asked whether he would have done anything differently as president.

“I wish I’d sent one more helicopter to get the hostages and we would have rescued them and I would have been re-elected,” Carter said, not for the first time in a public setting.

In fact, the hostage crisis unfolded against the backdrop of the 1980 presidential election, in which eventual Republican nominee Reagan campaigned on a combination of get-tough foreign policy and sunny American optimism. Carter, meanwhile, hunkered down even more, canceling most of his primary campaigning to focus on freeing the 52 remaining hostages.

Election Day 1980 was also the first anniversary of the embassy takeover. Americans delivered a crushing victory to Reagan. The new president was taking the oath of office when the hostages were finally released. The former president left the White House for the last time and flew to Germany to greet them.

And then he went back to the one place he could always call home.

IV. After the presidency

Carter was only 56 when he was turned out of the White House to face what he later described as “an altogether new, unwanted and potentially empty life.” There was “never any serious discussion we’d go anywhere else but Plains,” he told the AJC in 2014. “We’ve owned the same land since 1833, our church has always been there.”

But all was not well at home. The family’s peanut warehouse, which had been put in a blind trust during Carter’s presidency, was $1 million in debt and had to be sold. Their longtime church, Plains Baptist, had recently split over race. A splinter group that felt the church wasn’t welcoming Black worshippers had formed a new fellowship, Maranatha Baptist. The Carters switched their membership and became active worshippers and volunteers at Maranatha.

Three decades later, when lines would begin forming five hours early to get into Carter’s Sunday school class, church members would warm up the crowd by telling them about the former leader of the free world who’d made the altar cross in his home woodworking shop and who still cut Maranatha’s grass sometimes. It was a far cry from those early years, when Carter’s return to the place and things he knew best had drawn less notice outside of South Georgia.

Like many of his recent predecessors, Carter had signed a deal to write his memoirs and busied himself with plans for building his presidential library. But he hated asking people for money to “store White House records,” as he later put it; there had to be something better to do with the library slated for a 30-acre plot in east Atlanta overlooking downtown.

Enter the Carter Center. The idea for a place devoted to peaceful conflict resolution came to him in a dream one night, inspired by perhaps his greatest presidential achievement.

“Jimmy was sitting straight up in the bed,” said Rosalynn Carter, recalling his words: “‘If there had been such a place, I wouldn’t have had to take Prime Minister Begin and President Sadat to Camp David.’”

The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and the adjacent Carter Center opened in 1986. The focus quickly broadened to advancing human rights, health and democratic elections worldwide.

In May 2015, the Carter Center observed its 100th election, in Guyana. But it was with the very first election that they observed that Carter and his namesake operation sent an unmistakable message about their willingness to confront tough situations head-on.

In 1989, Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega and other officials attempted to steal an election that wasn’t going their way. Infuriated, Carter climbed atop a platform in the election commission and demanded to know, in Spanish, whether the balloting officers were thieves. Then he called a press conference and told the world the vote was bogus.

Credit: The Carter Center

Yet some of the most important work during Carter’s lifetime occurred further from the spotlight — and felt even closer in spirit to that young Navy officer who’d once wanted to make a direct impact on people’s lives. The Carter Center took on Guinea worm disease in 1986, when 3.5 million cases existed in 21 countries in Africa and Asia, and reduced that number to five reported human cases in just two countries during the first half of 2021. It helped to bring trained mental health clinicians to every county in Liberia, wipe out river blindness in four Central and South American countries, and standardize election practices in more than 60,000 Chinese villages.

“Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter have done more good things for more people in more places than any other couple on the face of the Earth,” President Bill Clinton said in awarding them the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1999.

But Carter had also angered Clinton in 1994 by holding his own nuclear talks with North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung and by going on CNN to discuss the results of an official trip to Haiti before he’d even briefed the president. Conservatives chafed when he sat down with Fidel Castro in Cuba in 2002, part of a growing chorus of criticism of his freelance diplomatic efforts. Where Carter saw instruments of his lifelong commitment to promoting peaceful dialogue everywhere, others saw dangerous meddling in foreign affairs. Or, crueler still, one last Carter campaign, to finally claim his own Nobel Peace Prize.

He pretty much shrugged off the haters.

“I take action every now and then that’s not completely acceptable to everybody on Earth,” Carter said to knowing laughs at a Carter Center town hall meeting in 2014.

That time, the criticism was about his decision to deliver the keynote address at the Islamic Society of North America’s annual convention. In 2011, it was his return visit to North Korea. In 2006, his pointed critique of Israel’s occupation of Gaza in his book “Palestine: Peace not Apartheid,” which prompted 14 members of a Carter Center advisory board to resign in protest.

It was 12 years since he’d won the Nobel, almost 35 since his “potentially empty life” had found new energy and a sense of purpose.

Why on earth would he stop now?

V. Cancer and Sunday school

On a warm Sunday morning early in May 2018, nearly 200 people stood on line outside little Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, trying to hide their disappointment. They’d just heard there was no more room inside for Sunday school — with 475 folks packed into the main sanctuary, an overflow room and even the choir loft, the fire marshal and Secret Service wouldn’t allow anyone else inside for President Carter’s class.

At 93, Carter had just reduced his teaching load to two Sundays most months. As a result, the crowds of 200 to 300 visitors who’d steadily shown up on most “Jimmy Sundays” (as some Maranatha members and longtime friends referred to his teaching weeks) in recent years had gotten much bigger, much faster.

It wasn’t the first time he’d set out to do this. At his surprise 90th birthday party in 2014, Carter had confided between bites of peanut butter ice cream how he’d tried and failed at cutting back earlier in the year.

“There was kind of a nice outcry from all over town, ‘Please Mr. Jimmy, we don’t have anyone show up at our shops and restaurants when you don’t teach,’” Carter said with a shrug and a smile.

By then, he and Rosalynn had settled into a nice rhythm of spending about a third of their time traveling for work or pleasure; another third in Atlanta, where their efficiency apartment at the Carter Center had a Murphy bed that pulled down from the wall for the former president and first lady to sleep on; and the rest of their time in Plains, where Carter could paint and putter around in his woodworking shop, socialize with friends and family, and never miss a monthly board meeting of the Plains Better Hometown Program.

As he entered his tenth decade, he still read three newspapers every morning — usually on his iPad now. He was always writing: Books on foreign policy and Christmas traditions, on politics and growing old (published when he was a mere sprite of 74). He co-wrote one book with Rosalynn, another for children with daughter Amy, and at age 89, he hit the best-seller lists with “A Call to Action,” an examination of discrimination and abuse against women.

Every year, he spent a week building houses somewhere in the world during Habitat for Humanity’s “Jimmy & Rosalynn Carter Work Project.” Each autumn like clockwork he showed up at Emory University, where he’d been University Distinguished Professor since 1982, to good-naturedly answer questions from the latest freshman class: Serious questions such as dealing with ISIS and the racial tensions in Ferguson, Mo; and less serious ones, like what was his favorite ice cream flavor or his take on the movie “Argo.”

In August 2015, though, there was no disguising the dire turn in Carter’s life: Doctors had discovered four melanoma lesions on his brain, he said; what he didn’t say at the time, but would reveal later, was that he thought he might only have weeks left to live.

Not surprisingly for such an accessible ex-president, he told the world all about the cancer himself, during a live televised press conference at the Carter Center. There, wearing blue jeans and without any doctors or notes at his side, Carter spent about 40 minutes discussing treatment options, the future of his namesake organization and how he felt confronting his own mortality some six weeks shy of his 91st birthday.

“I think I have been as blessed as any human being in the world,” said Carter, who believed that by being so transparent, he could help educate and empower others to take on cancer. On a more spiritual level, he suggested, his message was “one of hope and acceptance. Hope for the best, accept what comes.”

He’d cut back on his punishing schedule as necessary to fight the disease, Carter said. But that wasn’t the same thing as giving in. Two days after he went from the press conference right into his first round of radiation treatment at Emory University’s Winship Cancer Institute, Carter played genial second fiddle at a birthday party for Rosalynn in Plains that doubled as a fundraiser for a pair of nonprofits there. A couple of months later, when civil unrest forced that year’s Carter Habitat build to be canceled in Nepal, the ailing ex-president headed to Memphis and hammered away all day on a Habitat house there.

Meanwhile, teaching Sunday school went on as usual — albeit a new version of usual. On the Sunday after Carter’s moving cancer press conference, nearly 800 prospective students had arrived at little Maranatha Baptist by sunrise and police had to turn cars around on State Route 45 and redirect their occupants to the old Plains High School. Carter taught the 10 a.m. class at the church, then sped down the road to the high school and taught it again to the overflow crowd. Afterwards, he and Rosalynn stood and posed for individual photos with everyone at both locations.

With his traveling cut back, Carter began teaching almost every Sunday and visitors kept pouring into Plains from all over the world. On Dec. 6, 2015, they were unexpectedly rewarded when Carter shared some good news at the start of the lesson: A recent brain scan had found no signs of cancer. Three months later, another class heard him say that his doctors had determined no more treatment was needed, although he would continue to receive regular scans and resume treatment if necessary.

In the years that followed, Carter seemed to revel in the extra time he’d been granted, even if he was forced to make some concessions along the way. Jason Carter took over as chair of the Carter Center board — still, it was his grandfather who flew to London in 2016 to tell the House of Lords about the nearing total eradication of Guinea worm disease and to wrangle $6.5 million in British government support of the program. In July 2017, he briefly and begrudgingly allowed himself to be hospitalized for dehydration in Canada during the annual Carter Habitat build — but made it back on site the next day in time for breakfast and the morning devotional.

By then, too, he no longer stood for every photo with Sunday school visitors, instead sitting in a chair beside his wife with Secret Service agents hovering nearby, just out of the picture frame.

“After church is over, Rosalynn and I will be up front and we’ll be glad to have photographs with all of you,” Carter told an oversubscribed Sunday school class in May 2018, flashing an impish grin. A pause. “Uh, I’m in church, so let me tell the truth. We’ll be willing to have photographs …”

He’d already detoured in the parking lot on the way in to take group photos with a busload of heartbroken folks from Florida who’d been shut out of class. And for 40 minutes after church, he’d sit up straight in his chair and smile broadly as more than 400 people got their one-of-a-kind photo with the man who’d staked out his unique place in history.

“He’s not racing against this notion of, ‘I have this many years and I have to get this done,’” biographer Brinkley said of Carter in his 90s. ”He is a complete and full and authentic man now, doing what feels natural and right.

“He is a man content.”

Carter is survived by his children Amy, Chip, Jack and Jeff; 11 grandchildren; and 14 great-grandchildren.

Credit: Rick Diamond / The Carter Center

Access to our Jimmy Carter coverage is made possible by our subscribers. Thank you.

Not a subscriber? Join us today.