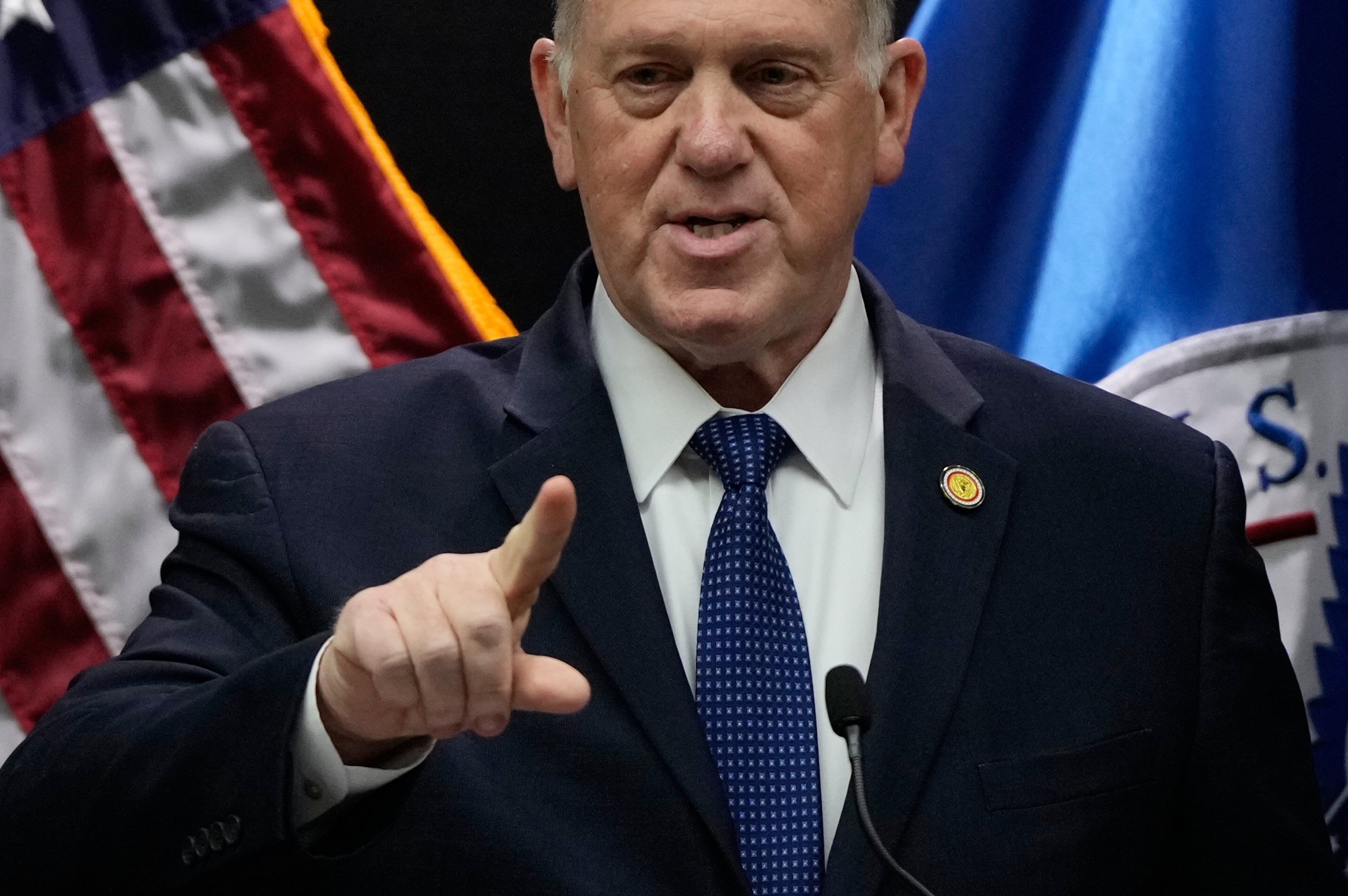

Former Georgia cop who had ‘a problem with females’ now running for Congress

Matthew Chappell’s brief career in Georgia law enforcement was marred by a string of misconduct linked to his pursuit of women in the communities and police agencies where he worked.

In 2016, he resigned in lieu of termination from the Glynn County Police Department after he tried to track a female acquaintance using the state’s criminal database and followed her home late at night in his police cruiser to pursue sex, records show.

Three years later, he was fired from the McIntosh County Sheriff’s Office after he shared nude photos with other employees that showed him having sex with a female sheriff’s staff member and another woman, records show. An internal investigation also cited him for pursuing a sexual relationship with a female officer of another agency while he was on duty and for posting inappropriate material on social media, records show.

“At this point, the only plan for improvement is termination,” a sheriff’s major concluded in January 2019.

None of it seems to have deterred Chappell’s ambitions.

Chappell, who now lives in Fairfax County, Virginia, is running for the Republican nomination in that state’s 11th Congressional District in a May 7 party convention and primary. Chappell’s campaign website shows a photo of him, his wife of 10 years and their three children on The Mall in Washington with the U.S. Capitol in the distance.

He has emphasized his support for cops as one of the cornerstones of his campaign. On his Facebook page, Chappell boasts of being the only former law enforcement officer and veteran in the race.

“If you see an officer today, thank him/her,” he wrote on his Facebook page. “The job takes a toll few will ever experience. I am blessed to have experienced this life, and I look forward to defending my brothers and sisters in Congress!”

Yet personnel files and Georgia police certification records reviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution point to an officer who lacked judgment and abused his authority. He was a cop in Georgia for just three years before the state revoked his police certification in 2019.

In an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Chappell discounted the entire investigation into the misconduct at Glynn County, saying that the accusations were all a “complete lie, complete falsehoods.”

Chappell’s troubles are emblematic of a broader problem within law enforcement, particularly in financially stretched smaller agencies in Georgia and elsewhere, according to police accountability experts. A strain on resources can undercut departments’ willingness to hold officers who misbehave publicly accountable, making it easier for troubled officers to move elsewhere when they get in trouble, experts say.

“The problem that I see is it’s systemic within the police subculture and many of the agencies across the country,” said Phil Stinson, a national expert on police misconduct.

Vulgar texts, a late night encounter

Chappell, 31, grew up in Eustis, Florida. After high school, he spent eight years in the military, including a deployment to Iraq when he was 18, his campaign website says.

He took a job in December 2014 with the Camden County Sheriff’s Office as a jailer, according to state records. A year later, he was hired by the Glynn County Police Department.

It didn’t take long for trouble to find him.

In 2016, Chappell was accused of sexually harassing a woman who tended bar at a bowling alley where he had worked as an off-duty police officer, according to an internal investigation. The woman told an investigator that Chappell started sending her a series of vulgar texts. One said “I would like to bend you over the bar one night” and another said “I don’t know why you won’t (expletive) me,” the investigative report said.

He asked her to send nude photos of herself and offered to send her photos of his genitals, records show.

Late one night, in February 2016, Chappell was on duty and used his patrol car to follow the woman home from her job, according an internal investigation report.

When the woman rebuffed Chappell for trying to touch her, he said she had been speeding and he could “arrest her and place her in handcuffs,” according to her allegations. The 6-foot-4 officer eventually grabbed the woman, picked her up, and kissed her on the neck as he was leaving, according to allegations in the report.

Months later, the woman reported the incident, prompting an internal investigation. The woman told an investigator that she had seen her car tag number on a computer screen inside Chappell’s vehicle the night he followed her, records show.

In an investigation interview, Chappell admitted many of the woman’s allegations were true, but denied misusing the state database, records show. He later told a supervisor that what he did was wrong and that all he wanted the night of the incident was “a piece of ass,” records show.

The investigator found Chappell had run several searches on the woman’s driver’s license and tag in the Georgia Crime Information Center and other databases used by police.

None of the searches were deemed work-related and they amounted to violations of the strict state policies governing use of this sensitive information, records show. It’s a violation of state law for officers to misuse the criminal database information outside of their official job duties.

Last year, GBI confirmed 17 violations of the system by officers, but the agency doesn’t track if any resulted in prosecutions.

In the course of the internal investigation, other women said they’d had problems with Chappell. He had been caught kissing a jailor outside of a detention center while on duty, and several female officers reported that he had hit on them, records show.

“Officer Chappell advised me that he has a problem with females and that it has caused problems with his marriage,” the Glynn County investigator wrote in his report.

In an interview on Wednesday, Chappell adamantly denied “using any database to look up a woman or follow her home.” He told the AJC he never admitted to any of the allegations during an investigative interview and that the report was “nothing but pure slander.”

“These are absolutely false allegations against me,” he said. “And they’re extremely defamatory. These kinds of allegations threatened to tear my family apart. It’s disgusting.”

Chappell left the Glynn police department in September 2016. Then-Chief Matt Doering said Chappell resigned in lieu of termination before a letter of termination could be completed.

Glynn County has a history of looking the other way and protecting officers who get in trouble, including former Lt. Cory Sasser who had a string of problems when he murdered his estranged wife and her male friend before killing himself in June 2018. Glynn County police failed to arrest the men, including a former officer, who were eventually convicted of murder in the February 2020 killing of Ahmaud Arbery near Brunswick.

Stinson, the national expert on police misconduct, said the way Glynn County handled Chappell’s case by allowing him to resign happens too often across the country with this type of misconduct.

He said chiefs, particularly in smaller agencies, regularly choose the path of least resistance by allowing officers to leave an agency without holding them fully accountable.

Stinson said the lack of consequences leaves the door wide open for an officer’s bad behavior to escalate later down the line with another agency.

“These are things we see with great regularity in my research, literally on a weekly basis,” said Stinson, a professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. “Often officers are given the opportunity to resign in lieu of criminal charges being pursued or in lieu of an internal investigation.”

Nude photos, more trouble

Chappell’s misconduct in Glynn resulted in a brief interruption in his law enforcement career in Georgia.

The Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training Council (POST) investigated his actions, and in July 2017 issued a public reprimand and placed Chappell’s state certification on two years probation.

That didn’t stop the sheriff in McIntosh County — one county north of Glynn — from hiring him in June 2018. Trouble followed Chappell up the coast.

The agency discovered that Chappell had been showing coworkers nude photos of himself and another female sheriff’s employee having sex together with another woman, records show. Sheriff Steve Jessup issued Chappell, who lived just across the state line in Florida, a warning that if he didn’t straighten up he would be fired.

The sheriff said “that he didn’t want to judge Chappell or even know what Chappell did in his personal life but this kind of thing, he better keep in Florida,” records show.

Our reporting

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution began requesting records on Matthew Chappell’s law enforcement history in February after learning about his campaign for Congress. The AJC obtained and explored personnel files from the Camden sheriff’s office, Glynn County police department and McIntosh sheriff’s office, which included internal investigative reports and records from the Peace Officer Standards and Training Council. The AJC reached out to the GBI, the state agency that monitors the Georgia Crime Information Center database, for insight on GCIC rules and regulations. A reporter contacted Matthew Chappell ahead of this story’s publication and interviewed him about the details included in the personnel files. A reporter attempted to contact victims named in police files, but was unable to reach them. If you have information about police misconduct or sexual harassment in law enforcement in Georgia please contact reporter Asia Simone Burns at asia.burns@ajc.com.

Other problems surfaced. Chappell posted inappropriate messages on social media that the sheriff found reflected poorly on the department, records show. Then in January 2019, Chappell allegedly contacted a female officer in Glynn County via Facebook while on duty and extended an open invitation for her to have sex with him, records show. Chappell offered to send the woman photos of himself with other women, records show. The woman declined his offer.

Chappell’s name surfaced again that same week connected to a suspicious incident in Glynn County.

A woman filed a complaint that a McIntosh deputy in a marked patrol car followed her to her house in Glynn County and asked for her license, even though the deputy was outside of his jurisdiction. The woman described how the patrol car pulled into her driveway behind her and said the driver, dressed in uniform, got out and asked for her license, according to a police report.

“She told him he could call the GCPD and have them come and she will show it to him then,” the police report said.

An investigator later showed the woman Chappell’s photo, and she said she was “almost positive” that he was the McIntosh deputy who had followed her, the report said.

Chappell was fired from the McIntosh sheriff’s office one day after the Glynn police report was filed, though the incident was not listed as the reason for his termination.

Chappell’s state police certification was revoked in October 2019 following a POST investigation.

‘born into sin’

By any measure, Chappell’s campaign in Virginia is a longshot. He is one of five candidates running in the Republican primary in a district that leaned heavily Democratic in 2020. According to Ballotpedia, Chappell was second in fundraising among his Republican counterparts with just $27,870 raised through mid-April.

He is emphasizing his status as a veteran and a former law enforcement officer to appeal to voters in Fairfax County in suburban Washington. His campaign website shows a photo of him in his Glynn County police uniform.

Chappell told one interviewer that when he wore a badge he tried to focus on the benefits of being a policeman, including interacting with the public.

“I met officers who should have never been allowed to wear a badge,” Chappell told a local Fairfax County news site in February. “I’ve worked with people who weren’t doing it for the right reasons, and I’ve stood at the forefront of calling these people out.”

He’s pushing for support ahead of the May 7 Republican primary, hoping to eventually run in November to unseat the Democratic incumbent Rep. Gerry Connolly, who has held the office since 2009. According to Chappell’s social media, he is building a campaign on the belief that “what you see is what you get.”

“This common perception that politicians are mythical creatures who have done no wrong and live up on a pedestal is simply untrue,” he wrote in a Facebook post in November. “Humans were born into sin (mistakes). We either learn from them and grow, or we don’t.”

Data reporting specialist Jennifer Peebles contributed to this story.

OUR REPORTING

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution began requesting records on Matthew Chappell’s law enforcement history in February after learning about his campaign for Congress. The AJC obtained and explored personnel files from the Camden sheriff’s office, Glynn County police department and McIntosh sheriff’s office, which included internal investigative reports and records from the Peace Officer Standards and Training Council. The AJC reached out to the GBI, the state agency that monitors the Georgia Crime Information Center database, for insight on GCIC rules and regulations. A reporter contacted Matthew Chappell ahead of this story’s publication and interviewed him about the details included in the personnel files. A reporter attempted to contact victims named in police files, but was unable to reach them. If you have information about police misconduct or sexual harassment in law enforcement in Georgia please contact reporter Asia Simone Burns at asia.burns@ajc.com.