FDA considers ban on menthol cigarettes

David Cato looked at his pack of cigarettes and the one smoke left in it.

It was early in the morning. He hadn’t eaten breakfast yet. And, in his months-long attempt to break a 40-year habit, he was at his daily crossroad — whether to buy another pack or resist the urge.

“My radiator hose went out on my car, so that might help me,” said Cato, an Atlanta-based concert promoter. “But I can still just walk to the store.”

For millions of smokers trying to quit, it can be an hour-by-hour, day-by-day struggle. Public health experts say that struggle is even harder when it involves menthol cigarettes. The minty-flavored cigarettes are heavily marketed, easier to get hooked on and disproportionately harm Black Americans.

After years of lobbying by activists who want to see the sale of the cigarettes stopped, the Food and Drug Administration is facing a Thursday deadline to respond to a citizens’ petition seeking a ban on menthols.

Some, including Black Lives Matter advocates, have called on President Biden to come out in favor of the move as part of an effort to address racial health disparities.

A federal ban would have to be approved by the White House.

Last week, several members of Congress, including Georgians David Scott and Nikema Williams, penned a letter to the secretary of Health and Human Services calling for decisive action. “The tobacco industry must no longer be permitted to use menthol cigarettes to profit at the expense of the health of Black Americans,” they wrote to Xavier Becerra.

Delmonte Jefferson is executive director of the Durham-based Center for Black Health and Equity, which was formerly known as the National African American Tobacco Network. He said a ban “could be the end of the tobacco industry as we know it.”

Jefferson, who lives in Atlanta, has been pushing for the prohibition of menthol cigarettes since 2009 when Congress granted the FDA authority to regulate the tobacco industry.

That year, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act banned all intentionally flavored cigarettes except menthol, instead referring it to the FDA for further study.

The tobacco industry, which spends millions of dollars annually on lobbying against any ban or regulation, argues that there is no evidence that menthol cigarettes are more toxic than regular ones.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, menthol cigarettes currently make up 36% of all cigarette sales in the United States, the highest proportion since major tobacco companies have been required to report such data.

“Menthol is part of a billion-dollar industry for the tobacco companies,” Jefferson said. “The tobacco industry knows that menthol is their cash cow. The suffering of Black people keeps them in business.”

But some civil rights groups have come out against a ban. The Rev. Al Sharpton of the National Action Network argued that banning menthol could subject more Black people to police stop and frisk tactics.

He used Eric Garner, who was killed in 2014 by police on Staten Island, as an example. Garner was initially approached by police officers for selling loose cigarettes. In 2015, Sandra Bland was found hanged in a jail cell after she was stopped for a traffic violation and then arrested for refusing to put out a cigarette. In 2020, George Floyd was killed by police after he tried to buy a pack of cigarettes with what officers say was a counterfeit $20 bill.

Guy Bentley, director of consumer freedom research for the Reason Foundation, a Los Angeles-based think tank, described the potential ban as “a laser-guided policy against Black adults who make a choice to smoke menthol cigarettes, while white smokers can still have whatever they want.”

Both menthol cigarettes and regular cigarettes, Bentley said, “are equally dangerous. It is a policy of prohibition, which can lead to over-criminalization and policing of Black neighborhoods.”

Natasha Phelps, lead senior staff attorney at the Public Health Law Center, disagrees. The time to ban menthol cigarettes has come, she said.

“I don’t know how they couldn’t do anything but remove menthol. There is no reason not to,” said Phelps. “I am kind of expecting that they are going to do what is obvious. But I am hesitant about trusting the FDA to do the right thing, because they haven’t for so long.”

According to the CDC, Black people smoke less, but they die at higher rates from smoking-related heart disease, cancer and strokes. About 45,000 Black people die annually from smoking-related illnesses ― more than from homicide, police violence or AIDS. Black men have the highest rate of lung cancer in the nation.

“Race is the number one indicator when it comes to your health outcomes,” Phelps said. “You can’t deny that when you are doing public health policy.”

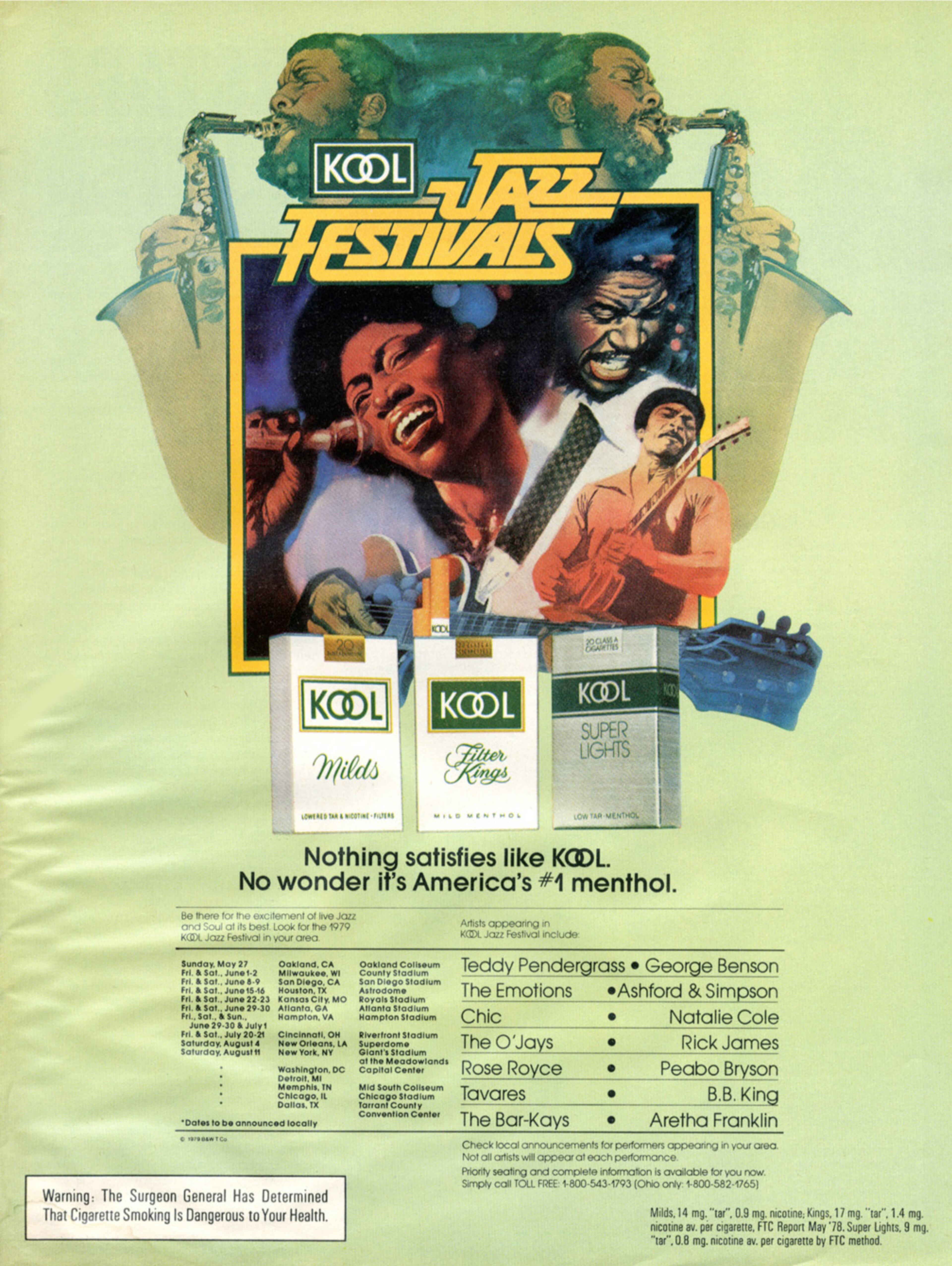

Popular menthol brands like Newport and Kool are consumed by more than 80% of Black smokers.

Between 1980 and 2018, menthol cigarettes “were responsible for 10.1 million extra smokers and 378,000 premature deaths,” according to a recent study published in the Tobacco Control journal.

Rosemarie Gambrell has been smoking Newport for 40 years and calls the habit “gross.”

Recently diagnosed with bronchitis, she used to smoke about half a pack a day. But she’s stretched one pack out over the three weeks that she’s been trying to quit.

“I enjoy smoking. There is nothing like a cigarette after you eat or with a cocktail,” said Gambrell, 62. “Not that I have experience, but I think it would be easier to wean yourself off of drugs than cigarettes. Nicotine is a really bad addiction. You crave it.”

Menthol cigarettes have been heavily marketed to Black communities at least since the early 1950s post-war boom.

Derived from a substance found in mint plants, menthol is the same agent used in lip balms and cough medicines to relieve throat irritation. It is also a penetration enhancer for topical drugs like IcyHot and VapoRub.

In cigarettes, it creates a cooling sensation and makes smoking more tolerable by masking the harshness of the smoke on the throat and lungs.

“They shouldn’t be putting flavor into poison,” said Phillip Gardiner, a co-chairman of the African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council.

“Menthol is the ultimate candy flavor,” he added. “It helps the poison go down better. It tastes good while it is killing you.”

Gardiner said that, as early as 1953, tobacco companies discovered that Black smokers preferred menthol brands at twice the rate of white smokers.

“So, we became targets,” Gardiner said. “It dawned on them that there could be different smokes for different folks. They literally pushed it down our throats.”

In 1953, only 5% of Black smokers smoked menthol. By 1976, it had reached 42%. Now, 85% of Black smokers rely on menthol brands. Only 29% of white smokers prefer menthol.

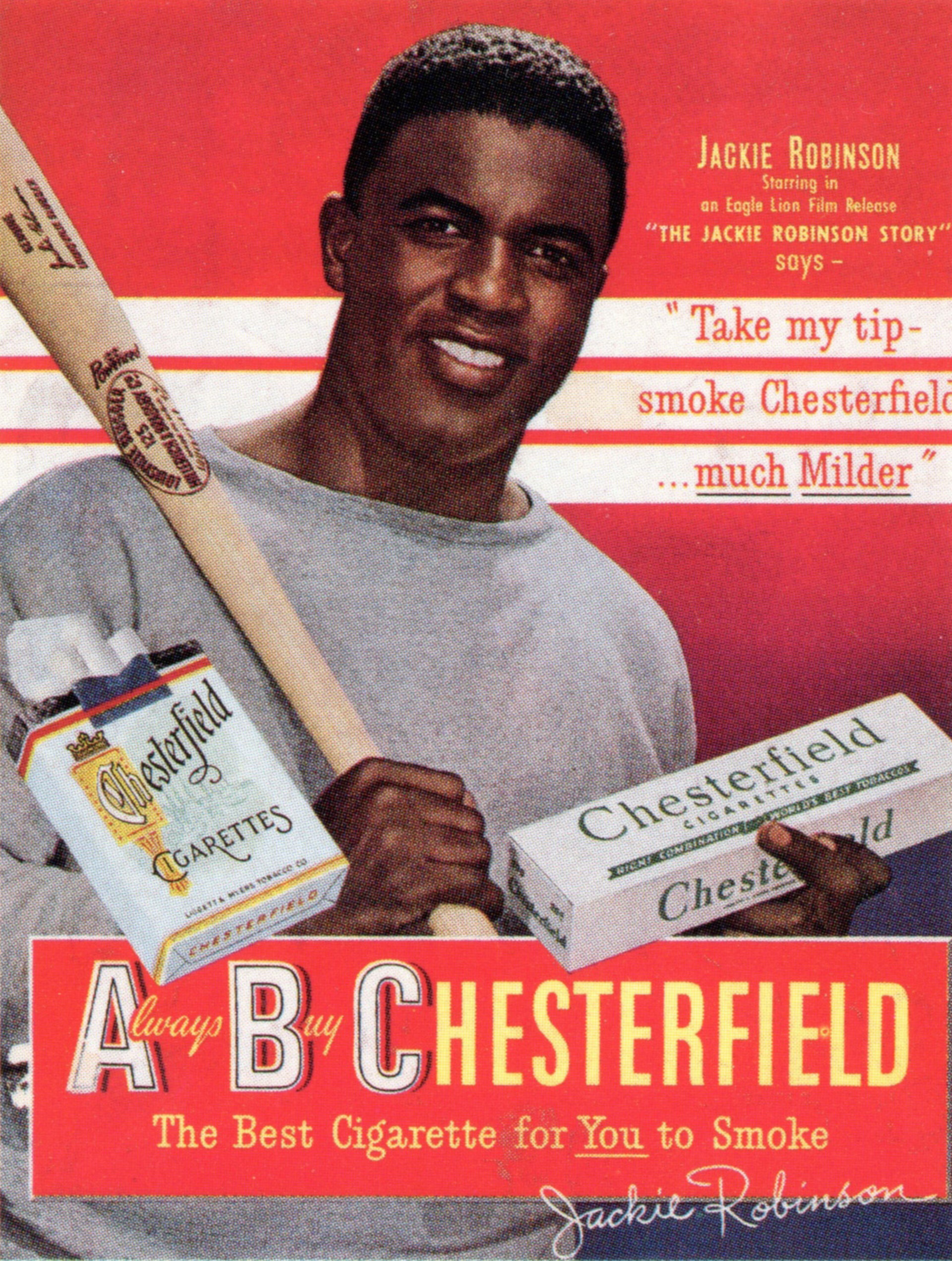

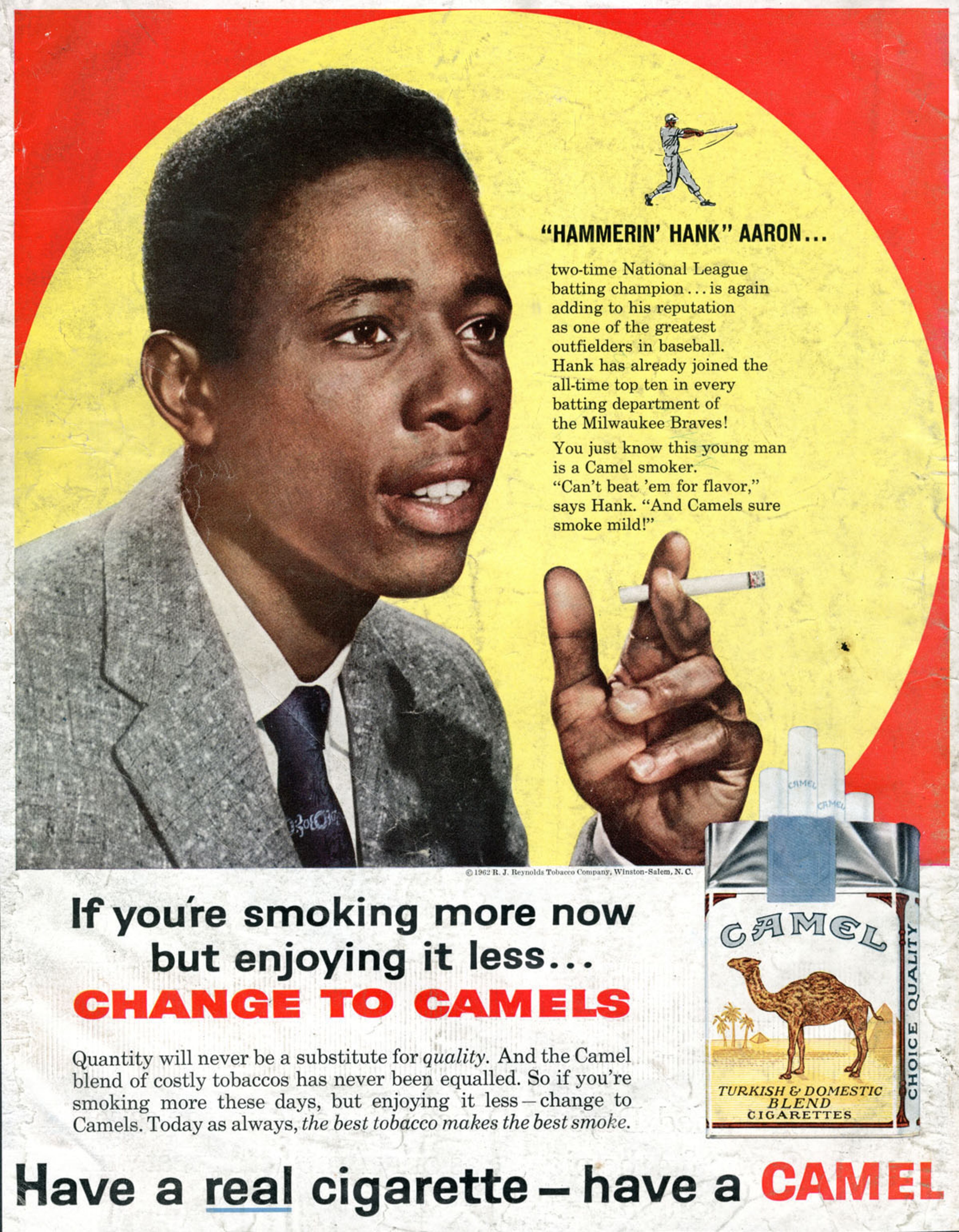

Tobacco companies gave out free samples and plastered stores and neighborhoods with posters and sponsorship banners, public health experts note. They bought ads, curated by Stanford University Research Into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising, in Black newspapers and magazines featuring Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Elston Howard and even Atlanta’s Hank Aaron. They donated to Black organizations and Black colleges and sponsored cultural events, like the long-standing and popular Kool Jazz Festival.

Some even argue that Joe Camel, the advertising mascot, was Black.

Last fall, the H.E.A.R.T. (Health, Education, Awareness and Research on Tobacco) Coalition, a local group, launched “No Menthol Movement ATL.”

The campaign addresses predatory marketing to Atlanta’s vulnerable populations, said D’Jillisser Kelly, the coalition’s program manager.

Cato is ready for change. Though his annual physical was fine, he wants to better his odds of it staying that way as he approaches his 60th birthday — even if he did end up walking to the store that day to buy a pack of Newport.

“That is a hard habit to break,” he said. “It is so hard.”