Demand for virus tests falls in Georgia as White House pushes for more

In the first months of the pandemic, when the new coronavirus was spreading like wildfire, anxious Georgians sometimes waited more than a week for a test result — if they could even find a place to get tested.

Today, testing centers are stocked and ready to go. But fewer people are showing up.

“Across the state, demand for testing is declining despite substantial capacity,” Candice Broce, a spokeswoman for Gov. Brian Kemp said in an email on Tuesday.

The reasons for the drop-off aren’t entirely clear, though the virus’ spread in Georgia has slowed in recent weeks. But public health experts say the changing, confusing messages around testing — often from the federal government — may be partly to blame.

Testing initially was reserved for only the very sick and the most vulnerable. Then, when supplies in Georgia improved, everyone was encouraged to be tested. This week, the CDC angered public health experts when it said those without symptoms needn’t get tested, a position it later softened.

What’s more certain is that Georgia still isn’t testing enough people to contain COVID-19. That’s the conclusion of the White House Coronavirus Task Force and outside experts in Georgia.

The state’s rolling seven-day average of positive tests, which was about 10% on Thursday, remains double a key federal and international standard of 5% for surveillance of COVID-19. Georgia remains near the border of the White House task force’s red zone for positivity, indicating more testing is needed.

“Test positivity rate is one of the best measures of if we’re doing enough testing,” said Dr. Sarita Shah, an associate professor of global health and epidemiology at the Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. “It should be less than 5%. I’d like it to be much less than 5%. We’re about double that right now.

“If we’re double where we need to be, then we’re only reaching half of what we should,” she said.

COVID Exit Strategy, a nonpartisan public health initiative, projects that Georgia is still only testing about a third as much as it needs to, though that figure has improved slightly as the rate of new cases and positivity have declined.

Through Thursday, Georgia reported about 24,000 tests per day since Aug. 23, a decline of about 17% from the peak the week of Aug. 2.

Along with wearing masks, social distancing and washing hands, testing and contact tracing are two of public health’s best weapons to mitigate COVID-19.

Tests identify cases. Robust testing coupled with contact tracing can pinpoint who has the virus and help isolate infected and exposed persons to limit spread.

About two out of five people with COVID-19 don’t show symptoms or only express mild symptoms, and research shows these people carry and likely shed just as much of the virus as sick people and inadvertently spread it.

Testing a broader sampling of the population helps identify infected people whether they show symptoms are not, Shah said.

As schools and colleges are opening, she said, broad testing of the public is critical.

Since testing expanded in Georgia in April, Kemp has consistently urged Georgians to get tested.

Broce said the governor is considering redeploying Georgia National Guard “mobile strike teams” to address hot spots. Such teams have been used to buttress testing capacity in the early months of the pandemic and to conduct testing at long-term care facilities.

“Based on what we know from contact tracing and community outreach, long-term care facilities, social gatherings, religious establishments, and schools — including higher education — may be the best recipients of these enhanced resources to mitigate the spread of COVID-19,” Broce said.

Georgia DPH is active in traditional and social media encouraging testing. The state recently announced that a temporary testing mega-site will remain in service near Atlanta’s airport through Sept. 11, or about two weeks longer than originally planned.

The latest White House task force report recommended Georgia move to “community-led neighborhood testing especially in under-served neighborhoods,” and to have health workers reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of those neighborhoods to build trust.

The state and local health districts have done this for some time, joining forces with neighborhood groups, churches and civic associations to promote testing, according to DPH spokeswoman Nancy Nydam. Some even offer free meals to entice people to get tested.

Mixed-messaging

The federal messaging on testing isn’t always clear.

Trump personally has said too much testing makes the nation look bad, a view public health experts have said is ludicrous.

On Monday, the CDC changed its guidelines to exclude people who don’t have COVID-19 symptoms. People who have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, the CDC’s updated guidance said, also don’t necessarily need to get tested, with exceptions for vulnerable people.

The move triggered a firestorm among public health experts.

The American Medical Association said the guidance could worsen the epidemic.

“Months into this pandemic, we know COVID-19 is spread by asymptomatic people,” AMA President Susan Bailey said in a statement. “Suggesting that people without symptoms, who have known exposure to COVID-positive individuals, do not need testing is a recipe for community spread and more spikes in coronavirus.”

By Thursday, the CDC walked back the changed guidance a bit.

CDC Director Robert Redfield said “testing may be considered for all close contacts of confirmed or probable COVID-19 patients,” according to the New York Times.

Georgia hasn’t changed its guidance, and still recommends people who may have been exposed to seek a test.

“One of the cornerstones of controlling this epidemic is test and trace,” Shah said. “This (new CDC guidance) is just another thing we’re going to have to deal with explaining to our community why testing is important.”

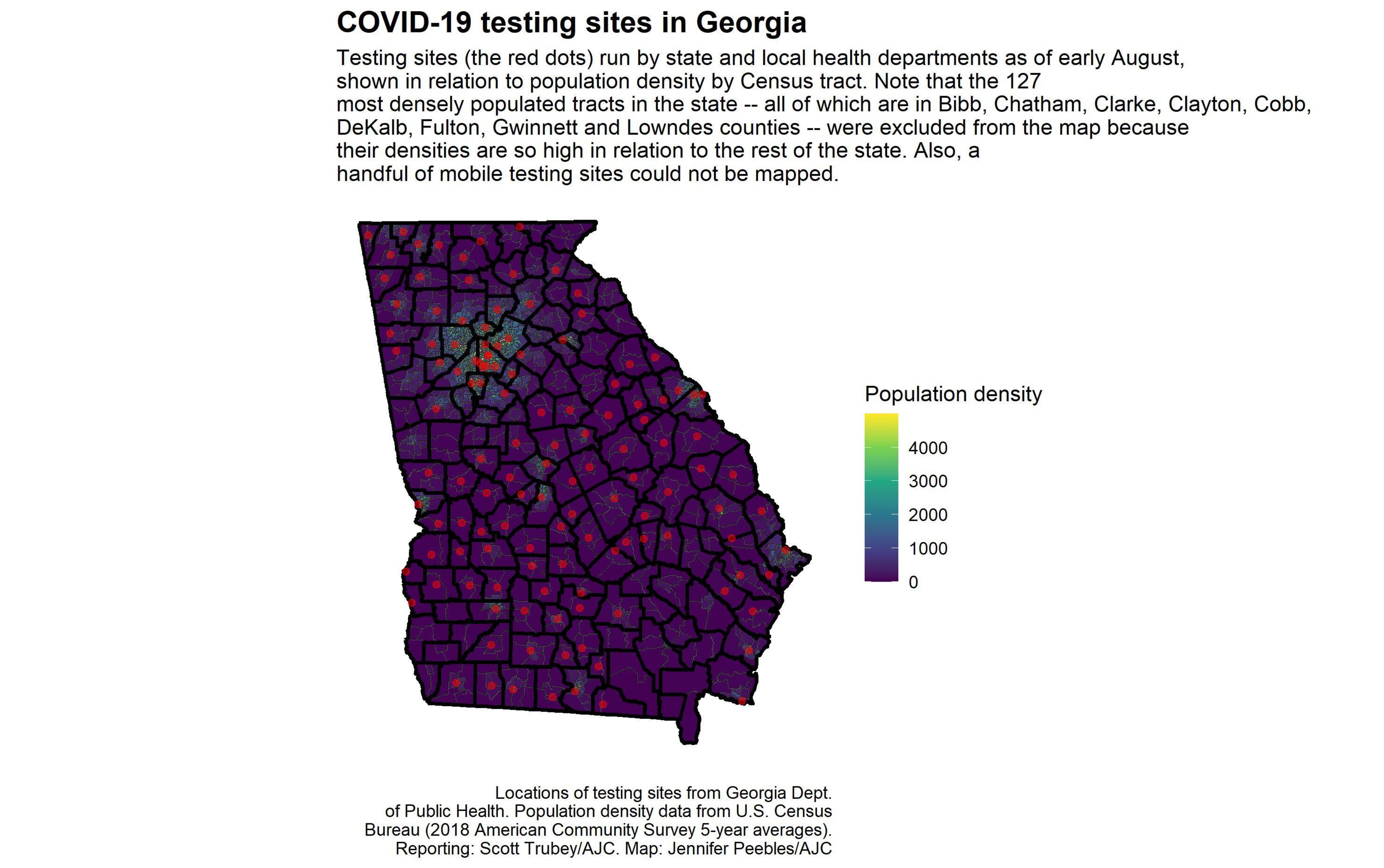

Issues in rural Georgia

The picture of testing in Georgia is as varied as the state’s 159 counties.

Places like Fulton and DeKalb counties in metro Atlanta are approaching a seven-day rolling test positivity rate of 5%, suggesting testing is closer to where it needs to be to more effectively track spread.

But drive southeast toward Savannah and counties around Macon and the sparsely populated communities along I-16 show much higher positivity rates.

The rolling average in Bibb County, home to Macon, was 14% on Thursday. In Toombs County, the rolling average was nearly 21% on Thursday and it topped 30% in Treutlen County.

In the Coastal Health District, which spans from Savannah to St. Marys, most counties posted seven-day averages for positivity of about 10% in recent days.

Dr. Lawton Davis, who runs the Coastal Health District, said his agency has plenty of test supplies, but demand also has fallen since a peak in mid-July.

Chatham County’s rolling average of new cases peaked July 24 at 141, according to Georgia DPH data, though positivity peaked about a week earlier at nearly 16%. On Thursday, the rolling average of new cases was about 49 with a rolling average of positivity at about 10%.

Davis attributed the Savannah region’s improvement to local officials’ relentless messaging for people to wear masks and to practice social distancing and mask mandates approved by Savannah and Chatham governments.

Davis’ department extended testing hours during the July surge and he said he expects to open more pop-up testing sites in the weeks ahead. He said the coastal district has the capacity if the region sees another surge.

“What I think is going to be interesting is to see what happens with Labor Day weekend,” he said. “If we have good weather and people are out and about partying you’d expect to see a blip five to 10 days after and you might see a surge three to six weeks afterwards.”

‘Not out of the woods’

In June and July, Georgia’s testing infrastructure, and that of the nation, was pushed to the breaking point amid sprawling outbreaks across much of the South and West.

Residents complained of waiting days to get an appointment and hours waiting in lines. It sometimes took a week or two for patients to learn their results.

The state boosted its testing capacity, and in the wake of national laboratories suffering prolonged delays, the state added new North Carolina lab vendor to process tests.

The nation’s testing apparatus is still fragile, experts say, and can again fall victim to supply chain disruptions. The gold standard for testing, known as molecular PCR tests, are constrained by the supply of machines and chemical reagents used in testing. Other bottlenecks can include the specialized swabs used to gather samples.

Nydam at Georgia DPH said turnaround times for test results have improved. Major national lab LabCorp, and Mako Medical, the state’s newest vendor, can process tests in about two days. The state’s public health lab can produce results in about a day, while Ipsum Diagnostics, a lab in Sandy Springs, has produced results on average recently in about 15 hours.

Quest, another national lab, is taking about seven days for non-priority samples, Nydam said.

One way around the current testing bottlenecks would be the wide-scale deployment of other forms of tests.

Companies are rushing to produce additional forms of antigen tests that are less expensive — though typically less accurate — than PCR tests, but these could be powerful screening tools if mass produced.

Though some currently are in use, they aren’t as widely available as many experts say the nation needs. But companies are working to change that.

Cold and flu season are quickly approaching, and scientists had hoped a lull in the summer would buy time to beef up the testing supply chain to be ready for the expected onslaught when COVID-19 cases are mixed with seasonal cold, flu and rising pneumonia cases.

Justin Bellante, CEO of BioIQ, a tech company that helps employers source testing, told the AJC in a recent interview the nation needs a diversity of test types to overcome issues such as constrained supply chains and to provide rapid results for workers in critical industries and to protect schools.

“It’s a much more challenging scenario going into the fall and this is a big red flag we haven’t figured out,” he said.

In DeKalb, testing centers are less busy and the Board of Health recently consolidated its six testing sites to four.

Dr. Sandra Elizabeth Ford, DeKalb Board of Health director, said some still may be discouraged by stories of long waits for appointments and results during the recent surge.

But DeKalb says its lab vendors typically return results in a couple days.

Dr. David Holland, chief clinical officer at the Fulton Board of Health, said Fulton scrambled to add lab capacity during the June and July surge. Wait times for results have greatly diminished and Fulton is expecting to soon add another testing site in Adamsville during the current lull.

Testing demand is down significantly, but he said the region must remain vigilant as decreased rates of new cases and improved positivity rate do not necessarily equate with having the virus under control.

“I want to caution everyone that we’re not out of the woods yet,” he said.

Staff writer Greg Bluestein contributed to this report.