Deadly outbreak at Dunwoody Health nursing home raises questions about reporting, oversight

As the coronavirus swept through hundreds of Georgia senior care homes this spring and summer with deadly force, Dunwoody Health and Rehabilitation Center reported to the state that it had remained a sanctuary from COVID-19.

Week after week, the massive 240-bed facility, actually located in Sandy Springs, filed statistics showing its residents remained safe and that just one staff member had tested positive.

“We thought everything was fine,” said Andrea Howard, whose father was a resident at the home.

In July, though, she and her brother, Shawn, became concerned that the rosy reports may not be accurate. They were told their dad, who had dementia, had spiked a fever but was OK. When they called for updates, though, the phone often rang repeatedly with no answer.

Finally, Shawn Howard talked to someone who relayed alarming news. His father’s roommate had tested positive. It was imperative, he said he was told, that he contact the state health department “as things were completely out of control at the facility with COVID-19.”

Howard called Fulton County officials urging a site visit to find out what was happening. Soon, the reality came to light. In a single day in mid-July, the state’s public report on the home shot up from zero cases among residents, to 63 residents with confirmed cases of COVID-19 and six deaths. The numbers kept going up, reaching 95 residents with the coronavirus and 15 deaths. At least 47 staff tested positive, too.

The Dunwoody case raises questions about whether some nursing homes in Georgia remain ill-equipped to quickly identify and contain outbreaks, and whether the oversight system is adequately protecting residents at a time when infection rates across Georgia are high, and family members and advocates are barred from visiting nursing homes because of the pandemic.

The state Department of Community Health, which licenses and inspects Georgia’s nursing homes, wouldn’t comment on what it had done to investigate the outbreak. Fulton’s health department said it was working with the home, but two scheduled site visits were canceled, apparently because DCH inspectors were at the home. Federal officials said Thursday the state had been ordered to visit the facility.

Every weekday, Georgia posts updates on the Department of Community Health’s website tracking the COVID-19 cases and deaths in nursing homes, assisted living facilities and large personal care homes. As of Wednesday, the report shows that more than 9,500 senior care residents statewide have tested positive during the pandemic and more than 1,600 have died.

The state doesn’t vet the information supplied by the homes, though, and the information isn’t reliable. Even though the list is supposed to capture all cases throughout the pandemic, homes disappear from the list of those with outbreaks without explanation, and case tallies, which are supposed to be cumulative, sometimes go down significantly.

“I think that there is pretty much no oversight or accountability right now, whatsoever, in nursing homes,” said Richard J. Mollot, executive director of the New York-based Long Term Care Community Coalition. “I find it absolutely terrifying.”

‘Unsettling and scary'

Long-term care homes have watched the spread of the virus across Georgia with dread, given that their workers have a higher chance these days of being exposed to the coronavirus during their off-time and then bringing it into the facility unknowingly.

The number of long-term care workers testing positive jumped more than 50 percent in July, the AJC found.

The homes have complained they can’t be blamed for the large outbreaks in their facilities because they were not made a priority in the initial weeks of the pandemic and couldn’t get enough masks, gowns, gloves and tests to protect their residents and staff from COVID-19.

But the big outbreaks and deaths at Dunwoody and other homes continue to pop up, even now as testing and supplies are becoming more available.

Test results showing a new outbreak at Dunwoody Health started coming in July 2, said Annaliese Impink, a spokesman for the home’s operator, SavaSeniorCare. The Atlanta-based company is one of the nation’s largest senior care chains with facilities in 23 states and is one of five for-profit chains targeted in a congressional investigation launched last month to explore the coronavirus crisis in the nation’s long-term care facilities. The home said it had tested the entire facility in May after a small outbreak and the results were negative. The home had reported one staff member testing positive in earlier reports.

With 15 deaths so far, the outbreak is among the deadliest in Fulton County during the pandemic. “Each one of these deaths is a loss for the staff and residents of our Center and we offer our sincerest sympathy to the families involved,” Impink said.

The home, she said, was “doing everything in our power to keep our residents safe and protected.”

With more than 40 staff testing positive, Impink said the home screens workers daily, directs those who don’t feel well to stay home and continues to “work diligently” to secure enough workers for each shift, including calling on staffing agencies.

“While the number of positive cases trends upward across the state, we know that this is an unsettling and scary time for our residents and their family members,” Impink said.

The Dunwoody facility is not the only Sava nursing home in Georgia to report a major outbreak. Nine of its 12 homes have, the AJC found. Windermere Health and Rehabilitation, a nursing center in Augusta registered one of the earliest large outbreaks, when more than 70 residents tested positive in early April. Roselane Health and Rehabilitation in Marietta has reported 82 positive residents and 12 deaths, with 29 infected staff, as of late July.

Seema Verma, the administrator of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), told the AJC when she was in Atlanta on Monday that the performance of the nation’s nursing homes during the pandemic has been a “mixed bag.” Plenty of homes, she said, haven’t had any cases, even if they’re in hot spots, while others have prevented the spread of the disease after quickly identifying a case or two.

“Then we’ve had the other side of nursing homes, where we’ve come in and we’ve done surveys and we’ve found clear violations — anything from hand-washing and not cohorting [residents who test positive],” she said. The homes with the worst records and repeat violations should be fined, she said.

She also said that stories of deaths at homes that fail to take the rights steps are disturbing. “When you hear about these stories, they’re tragic and they’re terrible and it calls for action,” she said.

Reports delayed

It is unclear how quickly the outbreak developed and whether various agencies were notified before the public reports revealed the problem.

The Dunwoody nursing home said it notified the state of the outbreak by July 5. But the state said that the outbreak figures weren’t reported until 10 days later.

The nursing home did report an outbreak to the federal database on July 12, said CMS, which regulates nursing homes at the federal level. That prompted CMS to send Georgia inspectors to the home on July 16 to check on infection control, but the state reported no violations, CMS said. As cases continued to go up at the home, CMS asked Georgia inspectors to go back for another check. That infection control survey is still ongoing, the federal agency said Thursday.

The state has yet to post a public report on its visits to the home, which could reveal if inspectors found any violations. As of Thursday, the most recent report for Dunwoody Health and Rehabilitation was for an inspection conducted in June 2019.

Facilities are also required to report outbreaks immediately to local public health districts. The Fulton County Board of Health said the nursing home wasn’t aware of the requirement, and the county learned of the case after Shawn Howard called an elected official in Fulton.

Some advocates worry that homes haven’t been subjected to enough scrutiny by state inspectors during the pandemic. When the outbreaks began, Georgia inspectors called the homes but didn’t make on-site visits in the vast majority of cases because the state didn’t have enough masks and gowns to equip inspectors.

In June, CMS ordered states to complete on-site visits to check on infection control at every home by the end of July, but Georgia lagged behind most other states in completing the inspections.

Assisted living and personal care homes were not covered by the federal order because they are state regulated.

Because states are rushing to meet a deadline and inspectors are focused on infection control, they’re not taking a close look at neglect and other serious problems that many advocates fear is taking place due to short-staffing and the pressures of the pandemics, Mollot said. “The inspections themselves are really cursory,” he said.

Questions remain

Shawn Howard was told that his father had tested negative for the coronavirus.

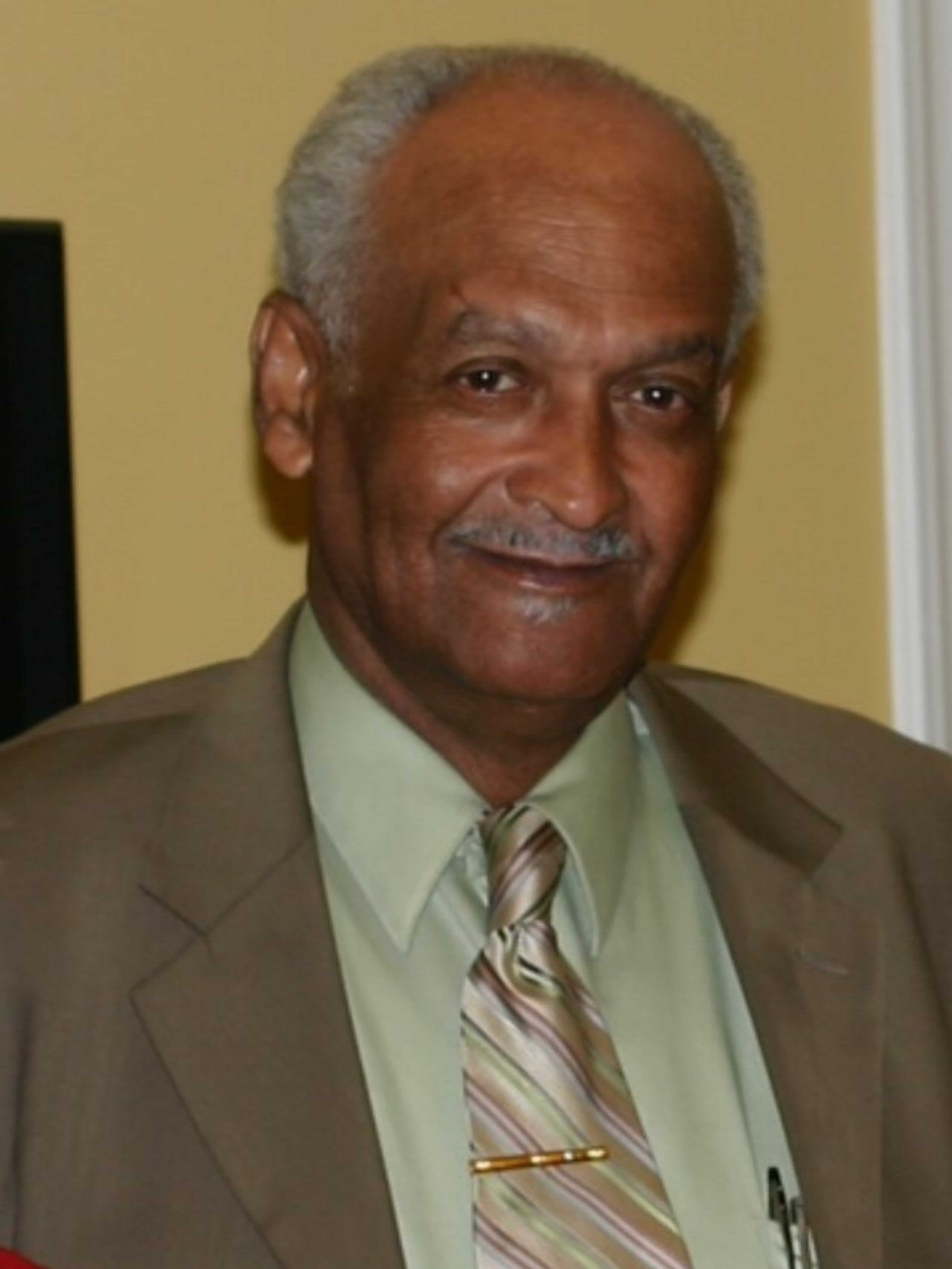

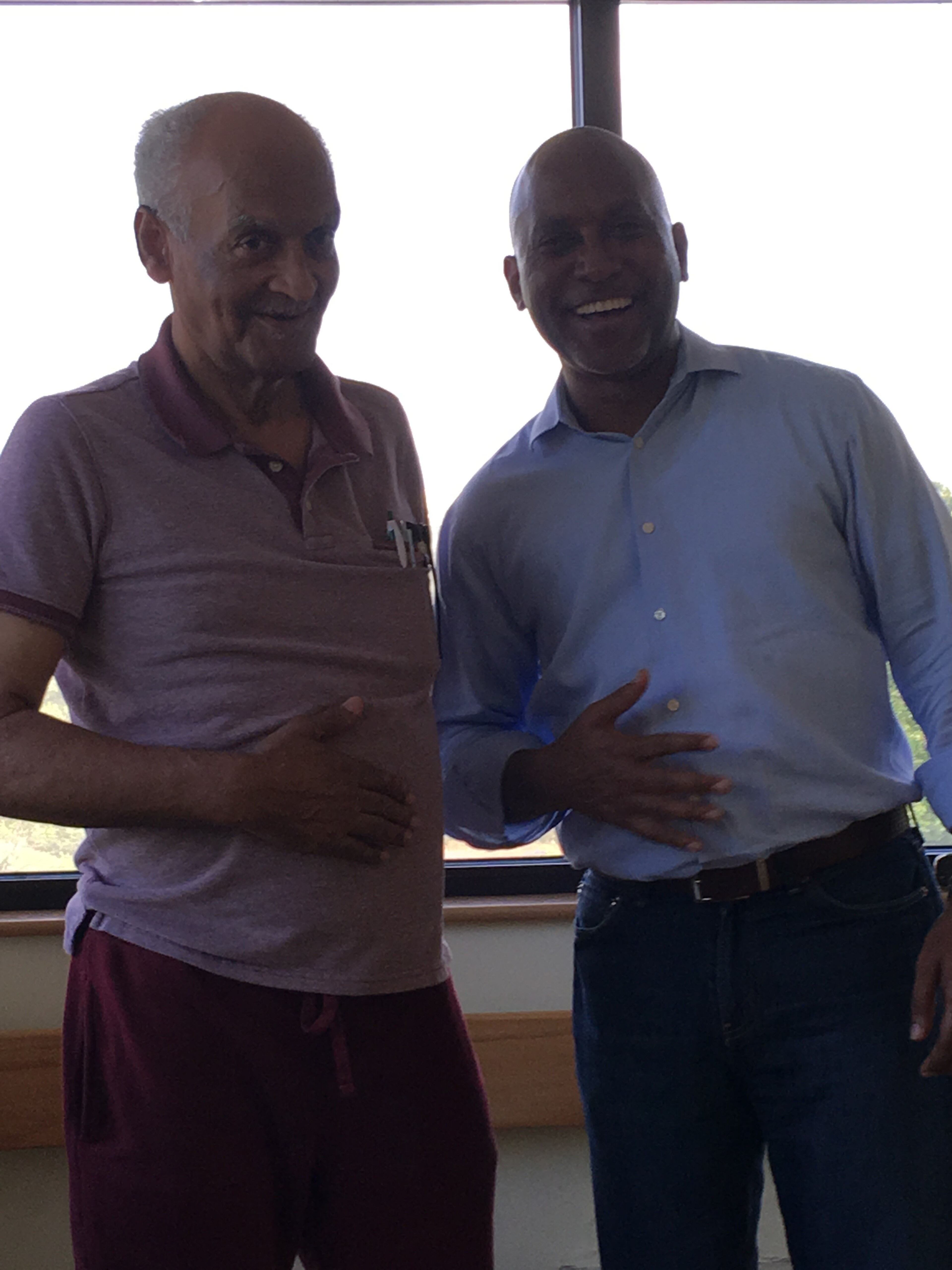

He asked, though, that his dad be transferred to the hospital after hearing he was lethargic after having a fever. Doctors quickly determined that Charles Howard did indeed have COVID-19, his son said.

COVID-19 was battering his body and he was sent to the ICU.

What’s more, he arrived dehydrated, suggesting he may have been malnourished, his son said.

Charles Howard was in the nursing home because he had dementia that set in after a 2018 car accident. “He did have dementia but physically he was in great shape,” his son said.

Andrea Howard was allowed to go to the hospital to see her dad, aware it might be for the last time. She donned full PPE, and entered his room. He was conscious, but confused and weak. “I said I love you, he mumbled I love you, too,” she said.

He died two days later, on July 24. He was 75.

His children embarked on the task of planning a funeral that many family members can’t attend because of the pandemic.

Shawn Howard still doesn’t have all the answers about what happened during the days that led up to his father’s death. He wonders why the nursing home’s tests didn’t pick up the virus. He wonders if more lives could have been saved if the facility had acted faster or if authorities were watching nursing homes more closely. He’s wondering what precautions were being taken, and whether the home had enough staff to properly care for his dad and others.

He’s wondering how many more residents won’t make it, and how many staff members will end up getting sick too.

“I still have a lot of questions,” he said.