By the time the confrontation ended, roughly 100 bullets had been fired in the East Point apartment. Inside, Jamarion Robinson lay dead, his body riddled with almost five dozen gunshots.

The 2016 shooting resulted in Fulton County murder indictments against two men assigned to a U.S. Marshals fugitive task force. The case, now pending, will likely be decided over questions of use of force, self-defense and the oaths of office taken by the two defendants.

But before that can happen, a judge must decide where the case will be tried. Tapping into a rarely used statute, defense attorneys say that because Clayton County police officer Kristopher Hutchens and U.S. marshal Eric Heinze were acting as federal officers, they can be tried in U.S. District Court, not the Fulton courthouse just a few blocks away.

Credit: Fulton County Sheriff's Office

Credit: Fulton County Sheriff's Office

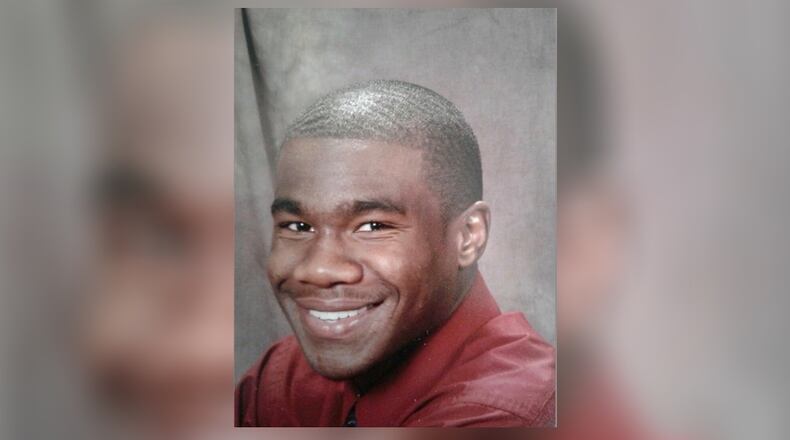

Robinson, 26, was killed by task force members inside his ex-girlfriend’s East Point apartment after allegedly refusing to surrender and shooting at officers. The marshals had come with arrest warrants for Robinson on charges he had committed two felonies.

His grieving mother, Monteria Robinson, says her son’s killing was unjustified. She and her family view the DA’s decision to indict the case last year as a small victory and hope it ends in the officers’ convictions.

Her son would have turned 32 on April 1.

Credit: Family photo

Credit: Family photo

“I just want to wake up from this nightmare,” she said after the officers pleaded not guilty last month in Fulton County court. “We’ve been waiting for six years.”

In 2018, Monteria Robinson filed an excessive force and wrongful death lawsuit against the members of the task force. But in a 56-page decision issued last year, U.S. District Court Chief Judge Timothy Batten sided with Justice Department lawyers defending the men and found the shooting justified. Robinson is appealing that decision.

After attending Tuskegee University for one semester in 2014, Jamarion Robinson moved back in with his mother at her Gwinnett County home. In the winter of 2015, he began acting unusual, saying he was seeing and hearing things. He was also found sleeping in a closet or the bathroom, according to court records.

He was hospitalized at a mental health facility for a week, diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and prescribed medication. But for most of the following year, he did not take his medication, court records said.

In the early morning hours of July 11, 2016, Robinson’s mother awoke to the smell of gasoline and called police.

Robinson had poured gas on the floor outside his mother’s bedroom and a woman who was also staying in the home told Gwinnett police she saw Robinson trying to set it on fire, court records said. Robinson fled before police arrived.

A felony warrant for attempted arson was taken out on Robinson, who didn’t return to his mother’s home after that, according to court records.

On July 27, 2016, Atlanta police officers were summoned to an apartment complex on a suspicious person call. When they attempted to detain the suspect, he drew a handgun and pointed it at them. The officers opened fire, but the suspect fled the scene, court records said.

Six days later, Atlanta police were called back to the same apartment complex on a complaint a squatter was living in one of its units. Inside, police found bags of clothing and a suitcase with documents bearing Robinson’s name. An Atlanta police officer later identified Robinson as the man who pointed a handgun at him during the earlier encounter.

For that, a second arrest warrant, this one for aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, was taken out on Robinson. The following day, the U.S. marshals fugitive task force received a request to find Robinson and arrest him.

On Aug. 5, 2016, Heinze, Hutchens and fellow task force members positioned themselves outside the front of the East Point apartment and rapped on the door. They announced they were law enforcement, which witnesses at the complex said they heard, court records said.

There was no response. And after an officer stationed behind the building saw someone look out of a second-floor window, the decision was made to bust open the front door.

Heinze entered the home first carrying a ballistic shield that was labeled “Police” and “U.S. Marshals,” court records said. Robinson, standing near the top of the stairs, was told to show them his hands and come down slowly.

Heinze has said that as he was alerting fellow officers Robinson had something in his hands, he realized Robinson was holding a gun, court records said.

“Believing Robinson to be a threat, Heinze discharged his firearm several times,” Batten’s ruling on the family’s lawsuit said. Daniel Doyle, another member of the task force, also opened fire.

Robinson retreated up several stairs after the initial shots were fired, and task force members instructed him to drop the gun and come out.

Over the next several minutes, Robinson would intermittently return to view and point the gun at officers before moving away. Each time, Heinze, Doyle and Hutchens “would respond to the threat with deadly force,” Batten’s ruling said. Hutchens later told investigators he saw “one or more shots” strike Robinson.

At one point, while Robinson was around the wall at the top of the stairs, Heinze, Hutchens, and Doyle said they heard two muffled gunshots coming from Robinson’s direction, followed by what sounded like the racking of the gun’s slide.

“Throughout the exchange, the officers felt that they were in a vulnerable position,” Batten wrote. “They also believed themselves to be at a disadvantage because of Robinson’s elevated position and ability to retreat from view.”

Robinson eventually collapsed face down at the top of the stairwell. As members of the task force moved farther into the apartment, they said they saw him “rolling back and forth.” He allegedly picked up the gun again and aimed it toward officers, prompting the officers to fire even more rounds.

Hutchens later threw a flashbang onto a second-floor hallway, and a robot equipped with a video camera was sent up the stairs so officers could get a better look, they told the GBI. Robinson was eventually pulled down the stairs by his ankles, handcuffed in the living room and rolled over onto his back. He was given oxygen and first aid at the scene, but it was too late.

Credit: Family photo

Credit: Family photo

A medical examiner’s autopsy found 42 bullets in Robinson’s body. Of the estimated 100 rounds fired that day, investigators determined 14 bullets were fired from a Glock .40 pistol, the gun Heinze was carrying, and 13 bullets or fragments “were consistent with having been fired from a Glock pistol.” Another four rounds were fired from Hutchens’ 9mm submachine gun and 34 were fired from Doyle’s .40-caliber submachine gun, which had been set to automatic.

In his order, Batten noted that another 26 bullets or fragments found at the scene could not be identified. Doyle died of cancer in March 2020 and was never charged.

The GBI recovered three .380 shell casings believed to have been fired by Robinson toward the officers below because they went into the wall at a downward trajectory. A HiPoint .380-caliber pistol covered in Robinson’s blood was found at the top of the stairs and gunshot residue was also discovered on his T-shirt, investigators said.

Monteria Robinson argues there’s no justification for shooting someone so many times.

“They knew my son Jamarion suffered from a mental illness,” she said, and “should have followed proper procedures” when dealing with someone suffering from such a disorder. Instead of opening fire, the humane thing to do would have been to contact a mental health professional or even get her to try to persuade him to surrender, she said.

Credit: Miguel Martinez for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Credit: Miguel Martinez for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

In court filings, the Fulton DA’s Office is opposing the bid by Heinze’s and Hutchens’ lawyers to move the case to federal court.

Hutchens is a Clayton County police officer, not a federal official, Deputy DA Lyndsey Rudder argued in a court motion. Moreover, Hutchens cannot rely on his special deputation to the marshals fugitive task force to claim he was acting under color of federal law, she wrote.

As for Heinze, he was acting outside his official federal duties because he violated the Fourth Amendment by entering Robinson’s ex-girlfriend’s apartment without a search warrant, Rudder wrote. The same would apply to Hutchens, who became “the aggressor” by illegally entering the residence, she said.

Defense attorneys for the two defendants argue that Heinze was a federal officer and Hutchens was working under the authority of the U.S. Marshals Service. They also cite court precedents that allow officers to enter an apartment without a search warrant if they believe it is the fugitive’s temporary residence.

Defense attorneys Don Samuel and Amanda Clark Palmer, who represent Hutchens, wrote they found “offensive” the prosecution’s assertion their client was the aggressor.

The officers had announced their presence with clearly marked shields identifying themselves as law enforcement officers, their motion said. “Robinson responded by grabbing a gun, pointing it at the officers and shooting it at them.”

The Latest

Featured