The first time Darnell Hudson found himself behind bars was in 2008. It became a cycle.

After serving five years in prison, plus eight arrest cycles in the Fulton County Jail, the now 33-year-old is hopeful he has found a way to break that pattern.

Hudson said training a rescue dog from the county’s animal shelter while serving time has helped him learn patience, and that getting what he wants doesn’t always require force. The Canine CellMates program, a charitable organization created in 2013, taught him that.

“I can’t keep doing this. I can’t keep coming to jail,” Hudson said. “(In the program) we’ve been talking a lot about communication, self-control, approaching situations differently. Every situation doesn’t necessarily need a response. Sometimes you can avoid things just by taking a second.”

Canine CellMates founder Susan Jacobs-Meadows said she has helped more than 300 inmates get one step closer to trying to break the cycle of incarceration by teaching repeat offenders patience and positive reinforcement through dog training. Invited speakers also teach the men life skills, including goal setting, job etiquette and how to successfully re-enter society.

The program has also helped more than 160 rescue dogs, mostly mixed breeds and varying ages, receive obedience training and get adopted. The dogs are only adoptable after also completing the program with their handlers.

For those taking part in the program, which included 11 men in the most recent cycle that graduated in September, their rescue pups stay with them at all times for 10 weeks, even sleeping at the end of their bunk beds in crates.

An extensive daily schedule is followed hour by hour by the men and corrections officers to ensure the dogs go outside to potty, eat, exercise and train at the same time every day. The dogs and their handlers are always escorted outside by officers.

Selection process focused on change

The participants are carefully selected, and those charged with murder, rape or manslaughter and anyone with more than three disciplinary write-ups are immediately disqualified. Jacobs-Meadows said she goes to the jail, shares about her work and then allows men to sign up for the program.

Usually leaving with about 150 names, she then has to get them all cleared by the jail, which includes medical and mental health evaluations. With a list of approved inmates, Jacobs-Meadows then interviews and chooses men who show a desire to change their current ways and better themselves.

She said she wanted her program to focus mainly on repeat offenders. She believes a man’s relationship with his dog can help him realize he is more than an inmate.

“Dogs have the ability to impart the change. They have the ability to look inside of us and find the good in every person,” she said. “People do bad things for all kinds of different reasons, but they’re not bad humans. Dogs have the ability to find that and also help that person see that.”

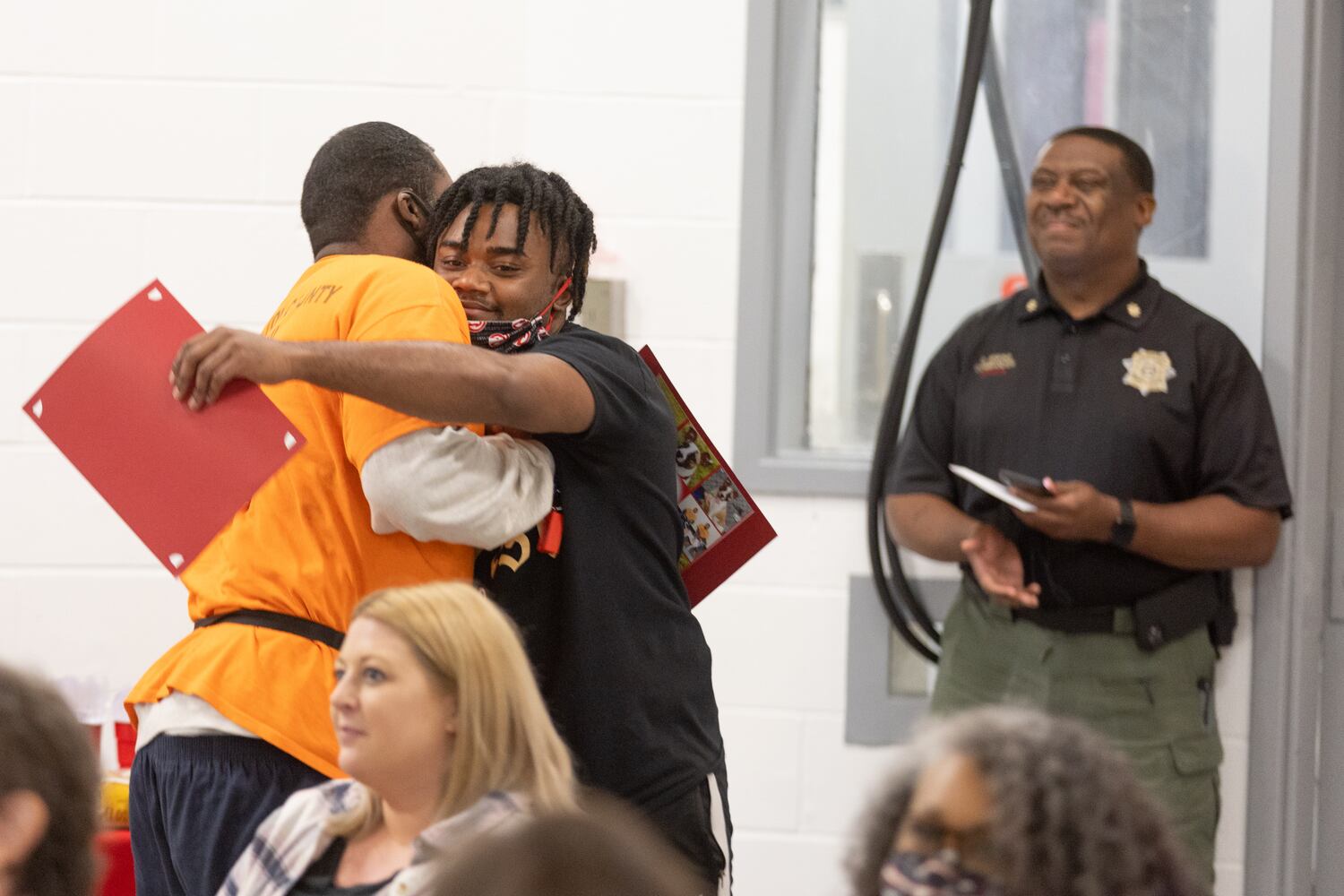

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Credit: Steve Schaefer

In 2021, Jacobs-Meadows decided to add a year-long program that takes place outside of the jail. “Beyond the Bars,” which currently includes 11 men who got an unsecured judicial release, serves as a disposition and rehabilitation program. The dogs in that program remain in kennels at Jacobs-Meadows’ facility, interacting with their handlers every weekday while they are at the facility. The dogs never go to the men’s homes.

Hudson, who was most recently arrested on charges including aggravated assault and possession of a firearm as a convicted felon, was selected to be part of that program and serve his time outside of jail by training his rescue pup Jake and attending life-skill classes.

“(Jake) taught me how to be a little more patient with dogs. You know, they’re kind of like us, you just got to take your time. We love them, they love you,” Hudson said. “This program really helps keep you out of trouble.”

Any opportunity to help those in jail better themselves is a chance to improve the county, Sheriff Patrick Labat said. He believes the rescue dogs become the men’s families during the program, helping them end the cycle of delinquency.

“Anytime we can have our detainees participate in any life skills, or life-building skills, and offer them an opportunity, we will do so. And everybody loves puppies,” said Labat, who has two dogs of his own. “Everybody wins.”

Turning loss, absence into reason

Mario Knight is confident he can start his life over.

The 34-year-old, who has been arrested eight times in Fulton and served two prison sentences, was most recently arrested on a drug trafficking charge, possession of a firearm by a convicted felon and failure to obey a stop sign.

He wants to be able to watch his three kids grow up and be there for them. Training Buttercup in the Beyond the Bars program has taught him the skills to re-enter society, he said, while also showing him ways to be a more devoted father.

“A lot of my community, a lot of us grew up without fathers. But the ones who had a father, they felt like their father was dead ... because their father was locked up,” Knight said.

After Jacobs-Meadows’ father died when she was 9 months old, her mother was left to take care of three children. That’s when Julie, a Boxer puppy, was introduced to the family and became the children’s guardian. Jacobs-Meadows experienced first hand the impact dogs could have on an individual, so when she read about a program involving those who are incarcerated and dogs, she knew she had to start her own.

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Credit: Natrice Miller / Natrice.Miller@ajc.com

Before Brandon McGill’s days were filled with taking care of his rescue dog Louis, he was mentally struggling while serving time for charges including reckless driving and obstruction of law enforcement. The 34-year-old, who has been locked up in Fulton 12 times since 2005, said Canine CellMates was the best thing that happened to him while in jail.

“(The program) taught me how to show love to animals, taught me how to be more patient. It helped me with expressing love and communicating with other people with all kinds of attitudes and demeanor,” McGill said.

The father of four knew he had to make changes when he noticed the trembling in his children’s voices when they told him they missed him, he said. He saw Canine CellMates as an opportunity to make his children proud and show them he cherishes them.

Self-compassion, even after mistakes

While the men in the program all expressed a desire to turn their lives around and never step within the walls of a jail again, Jacobs-Meadows said she understands mistakes can happen. Current and past participants of the program are like family to Jacobs-Meadows, meaning that a call for help will never be ignored.

“When you look at the population we deal with — that repeat felony offender — it’s unrealistic to expect that they’re never going to make a mistake again,” she said. “We can hope, right? But I do not think that making a mistake erases all of the positive change they made leading up to that point.”

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Roosevelt Micher Jr., who will turn 60 soon and has served five prison sentences since 1990, said he wants to spend the remaining years of his life with his family. Since serving time most recently for criminal trespass and entering a vehicle with the intent to commit theft, Micher was released in October, just a few weeks after graduating from the program.

“My mission is to help my shelter dog, the hurts that she went through, and at the same time help myself through love and instruction and understanding,” he said. “I don’t have much time to play around.”

Having experienced a lot of hurt throughout his life, he said his dog Merrell helped him realize why he went down the path he did. Micher said he was uncertain for many years if he was worthy of love, but Merrell helped him understand what unconditional love felt like.

He now wants to make sure those around him also understand that feeling.

“(Merrell has) made me more patient,” Micher said. “You can be out there in the streets, and there you love everything and everybody other than yourself. You put yourself in a lot of different situations, you can’t love yourself. So she taught me how to love me.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured