Rayshard Brooks’ final 41 minutes

It’s 10:42 p.m. at a fast food place in America.

For months, the coronavirus has ravaged the country, infecting people who stand too close or hug too tight. Protesters have gathered in the streets, demanding an end to police abuse of black people after several brutal videos emerged. People sheltering from the virus at home have watched competing horrors play out on TV and cell phone screens, beckoning them to react, comment, take a side.

Right now, though, at the Wendy’s on University Avenue in Atlanta, customers can agree on one thing: This drive thru line is barely moving.

The problem is a white Toyota Camry. The driver appears to be sleeping at the wheel, and cars are maneuvering around him. An Atlanta police officer arrives to check out the situation. At first, it seems as though this could turn into a mundane DUI arrest. But it doesn’t happen that way. Instead, another deadly confrontation between police and a black man unfolds. Someone captures it on video and, within hours, the grainy footage loops on TV and social media.

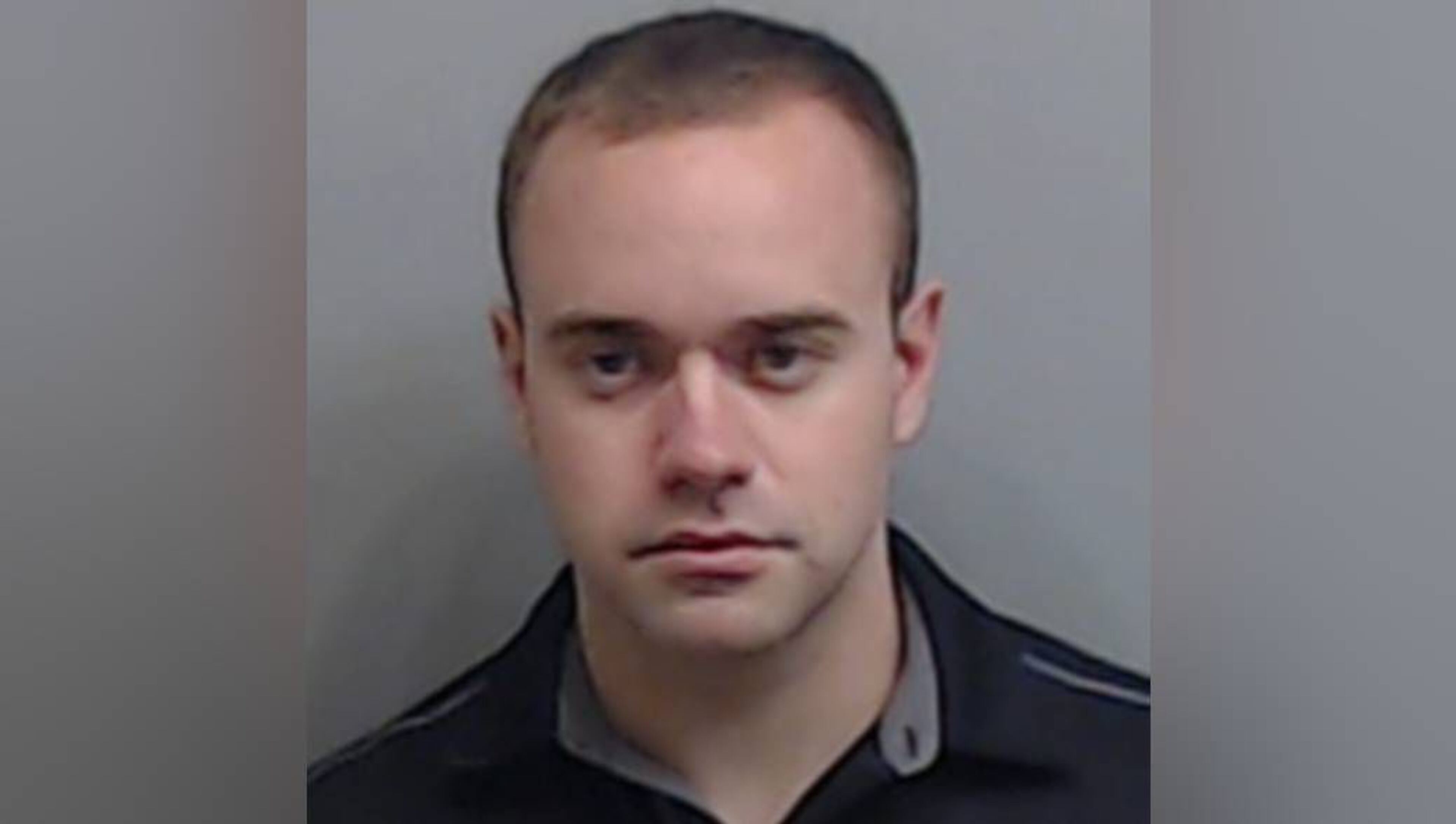

In the week since Rayshard Brooks died on June 12, the story has rocked Atlanta at breakneck speed. More protests erupted. The police chief resigned. The Wendy's was torched. Garrett Rolfe, the cop who shot Brooks, was promptly fired from the Atlanta Police Department. Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard charged him with murder and Devin Brosnan, the first cop to respond to the sleeping man, with aggravated assault.

In an apparent protest, some APD cops called out of work because they felt Howard rushed to judgment.

As a moment of national reckoning rages, Brooks and Rolfe have become avatars for their respective positions in the confrontation: Brooks, a stand-in for the black people who've fallen at the hands of police, Rolfe for the officers who've pulled the trigger. Officials, attorneys, politicians and residents are arguing over why each man behaved the way he did at Wendy's that night and why what could've been a forgettable encounter ended in death.

‘Just move your car’

When Brosnan shows up at Wendy’s, Brooks, 27, is leaned back in the driver’s seat, arms at his side, cell phone resting on his lap.

What videos had Brooks seen on that phone? Like most everyone else, he’s likely watched George Floyd die with a Minneapolis cop’s knee on his neck. He probably witnessed Ahmaud Arbery shot dead in Brunswick during a confrontation involving three white men. Brooks might’ve seen those black men’s relatives demanding justice, faces shiny with tears.

Brooks has a family, too — a wife, three daughters and a stepson; a late mother he misses; a father he only met in 2018 but has come to love. Momentarily, Brooks will be talking about family to police, but the officer must first wake him.

“Hey sir,” officer Brosnan says after cracking the door, “you all right?”

It takes a few tries to rouse the sleeping man. Eventually, Brooks looks at Brosnan, smiles as if a bit embarrassed. Brosnan asks him to move the car. Brooks agrees, but then falls back asleep. Brosnan wakes him again, and Brooks pulls into a parking spot.

Brosnan suspects Brooks is drunk. “I don’t want to deal with this dude right now,” the officer says to himself.

Brooks has been in trouble off and on since he was 10 years old. At 27, he’s been on probation five years and it’s scheduled to continue through 2026. He’s pleaded guilty to various charges. His most serious conviction was from a 2014 incident in which he yanked his wife against her will into another room in front of her son. Brooks pleaded guilty to false imprisonment and, because the boy saw the fight, child cruelty. He spent nearly a year behind bars.

Afterward, Brooks kept running afoul of the conditions of probation, which he found overly stringent. The curfew, fines, community service, fees and classes were hard for probationers to balance, he said in a February video testimonial for a criminal justice reform group.

“It’s hurting us, but it’s hurting our family the most,” he continued, adding that he wished probation officers would be more active in helping people in the system succeed and overcome the challenges they face with a criminal record.

“It’s a lot of pressure,” he said in the testimonial.

Questioning

At the Wendy’s, Brooks tells the cop he’s had just one drink.

Brosnan radios for a certified DUI officer.

Rolfe, who’s been with APD since 2013, points his patrol SUV toward Wendy’s. Rolfe, 27, the same age as Brooks, is a member of the department’s High Intensity Traffic Team, tasked with booking DUI drivers. In 2019, Mothers Against Drunk Driving awarded him a silver pin for racking up more than 50 DUI arrests in the prior year. Fellow officers see Rolfe as someone who was in the job because he was passionate about helping people and wanted to make service a career, according to a co-worker.

Rolfe had faced one serious allegation in his time on the force. A man accused him and two other officers of shooting into his truck in 2015 while arresting him. A bullet struck the man in his back, collapsing his lung. The officers failed to even mention that they'd fired their weapons in the incident report. Fulton Superior Court Judge Doris Downs reported the cops in 2016 after she was assigned to the man's case. Downs, who is now retired after more than three decades on the bench, said she'd never before seen a case where officers didn't mention a shooting in their report.

But this February, after taking five years to make a decision, District Attorney Howard found that Rolfe and the others engaged in “no criminal conduct.”

When he arrives at the Wendy’s, Rolfe asks Brooks what’s going on.

Brooks says someone dropped him off.

“The reason why we’re here,” Rolfe says, “is someone called 911 because you were asleep behind the wheel while you were in the drive thru, right? Do you recall that?”

“I don’t,” Brooks says.

“You don’t recall that?” Rolfe says, eyebrows raising. “You don’t recall just minutes ago when you were passed out behind the wheel in the drive thru?”

Brooks shakes his head, side to side.

“You don’t recall that at all? Just a complete blur?”

Brooks says he wasn’t driving. Someone dropped him off.

“I’m sorry,” Brooks says. “I’m not causing any problems.”

Rolfe says he has to make sure Brooks is good to drive.

‘I don’t want to refuse’

Brooks talks a lot, giving rambling and conflicting answers to Rolfe’s questions. He’s confused. He thinks he’s on Old Dixie Highway in Forest Park, which is 10 miles away.

Brooks agrees when Rolfe asks him to get out of the car. He agrees to a pat down. He does a field sobriety test, unsteady on his feet. He respectfully refers to the officer as “Mr. Rolfe.”

Rolfe asks how many drinks Brooks has had repeatedly, unsatisfied with the answer that Brooks keeps giving: a drink or a drink and a half. Rolfe asks: “On a scale from one to 10 – with one being completely sober, 10 being very impaired – how do you feel?”

Brooks misunderstands and says 10.

Brooks keeps talking. He says he’s come from his daughter’s birthday party. He suggests that he could just walk to his sister’s house, which is nearby. Rolfe doesn’t seem to consider it.

Brooks knows what a DUI might mean. He would spend time in jail, possibly prison because of his probation. He had been arrested last winter in Ohio for not telling his probation officer he had moved there two years ago. His father, who he met around the same time, lived in Toledo. Brooks liked the city’s slower pace and had found a job. Brooks talked about moving his family to Ohio to join him before the recent arrest brought him back to Georgia.

Rolfe asks if Brooks will take a breath test.

“I don’t want to refuse anything,” Brooks says. Rolfe walks to retrieve the breathalyzer while an expression of resignation, maybe dread, forms on Brooks’ face.

After Brooks blows, Rolfe checks the results: Brooks is above the legal limit by 35%.

The moment

Forty-one minutes into the interaction, Brooks hasn’t given the slightest indication he might try something. Rolfe doesn’t know about Brooks’ history, so he’s unaware that Brooks has resisted arrest before, an encounter that led to him being tased by Forest Park officers in 2014.

As Brooks is going on about his child’s birthday party, Rolfe reaches for Brooks’ wrists. “I think you’ve had too much to drink to be driving,” Rolfe says. “Put your hands behind your back for me.”

What is Brooks thinking?

Days later, psychologists will be among those watching the videos. Several will say Brooks is likely surprised by Rolfe's sudden movement to arrest him. When Rolfe grabs Brooks' left wrist, Brooks' thoughts might be racing, according to psychologists: What about my wife? What about my kids? What about prison? What about those videos?

Some policing experts also will say Rolfe shouldn’t have moved so quickly to cuff Brooks without pausing to explain. Others say Rolfe acted appropriately.

Brooks snatches his wrists back and tries to bolt. Rolfe and Brosnan struggle to contain him. The body cameras show tumbling.

“You’re going to get tased! Stop fighting!”

“Mr. Rolfe! Mr. Rolfe!” Brooks yells.

Brooks takes a Taser from Brosnan and breaks free. He strikes Rolfe. Rolfe hits Brooks with a Taser. Brooks sprints across the parking lot, the prongs still on him, Rolfe chasing with the Taser in hand. Cell phone cameras are already rolling.

What is in Rolfe’s mind?

Is he worried that Brooks could hurt him or someone else with the Taser? Is he worried what Brooks will do if he escapes? Later, Atlanta Police Union representative Ken Allen will say Rolfe is following his training: “You don’t let a suspect just run away once you’ve been engaged in a use of force.”

Almost simultaneously, Rolfe reaches for his gun as Brooks is turning around. Brook fires the Taser, apparently missing Rolfe. Brooks continues to run away. Rolfe fires his gun, striking Brooks twice in the back.

Brooks’ last moments

Brooks falls. “I got him,” Rolfe says, according to the district attorney.

“Put your hands behind your back!” Rolfe screams at Brooks.

While Brooks is on the ground, Rolfe kicks him, according to Howard. The other cop, Brosnan, allegedly stands on Brooks’ shoulders. Later, the officers’ attorneys will deny they did anything wrong. Howard will say it’s wrong to let two minutes and 12 seconds pass before rendering aid to Brooks, who will die after surgery, after a bullet pierced his heart.

Activists around the country have lately railed against what they call inappropriate efforts by police unions to protect cops from scrutiny. On the scene, Rolfe phones a local union rep to report the shooting before he speaks to investigators.

After Rolfe gives detectives a statement, he asks a supervisor: “Any update on Mr. Brooks?”

“I ain’t checked,” the supervisor says. “We’ll get that squared away. But you’re good.”

Staff writers Chris Joyner and Alexis Stevens contributed to this report.

-

HOW WE REPORTED THIS STORY

This account, a re-creation of the last moments of Rayshard Brooks’ life, is based on review of body camera video, police and court records, statements by officials, attorneys, various experts and people who are familiar with Brooks and the officer who shot him. Attempts to reach Brooks’ wife and secure interviews with Rolfe’s loved ones weren’t immediately successful.