In one of the most daring raids during the Civil War, Union saboteurs infiltrated North Georgia, seized a locomotive and sped toward Tennessee. They destroyed railroad tracks and telegraph wires along the way, with the goal of disrupting Confederate supply lines and capturing Chattanooga.

Much of the mission went according to plan on April 12, 1862 — until a determined group of Southern railroad workers caught up with them about 18 miles south of Chattanooga. It became known as the Great Locomotive Chase. The raiders were captured within two weeks. Though some eventually escaped, eight were hanged.

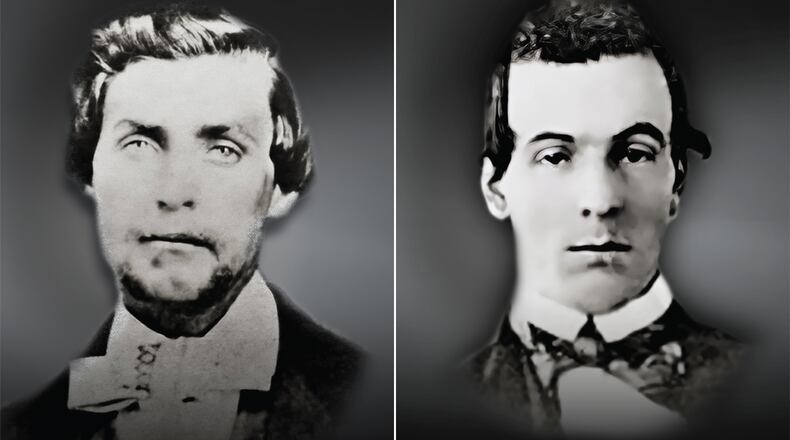

On Wednesday, President Joe Biden will posthumously award the Medal of Honor — the nation’s highest military award for valor — to two of those who were executed, Pvts. Philip G. Shadrach and George D. Wilson of the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Credit: Courtesy of the U.S. Defense Department

Credit: Courtesy of the U.S. Defense Department

At Biden’s invitation, Shadrach’s great-great-nephew, Gerald Taylor, plans to attend the ceremony with his children and grandchildren.

“I am very humbled and proud to be able to come down here and get this award,” said Taylor, a retired insurance executive from Ontario, Canada. “We are all so thrilled.”

Most the other raiders have been honored already with the medal, except for one who refused it and some civilians who were not eligible for it. Historians say it took so long for Shadrach and Wilson to be honored in this way partly because of an oversight. After the raid, their superiors were promoted to other regiments and transferred West, so Shadrach and Wilson had no one to advocate for them.

Brad Quinlin, a historian and author based in Suwanee, was among those who worked to get the medals approved. He painstakingly gathered historic records and met with White House and Pentagon officials and then-U.S. Rep. Rob Woodall. For Quinlin, it was a matter of fairness.

“I dug through thousands of documents,” Quinlin said by phone Monday as he drove toward Washington, D.C., to attend the ceremony. “It just ate at me.”

The historic chase made it to the big screen decades later. Buster Keaton starred in a 1926 comedy named after the locomotives the raiders stole, “The General.” And Disney released a film about it in 1956, “The Great Locomotive Chase.”

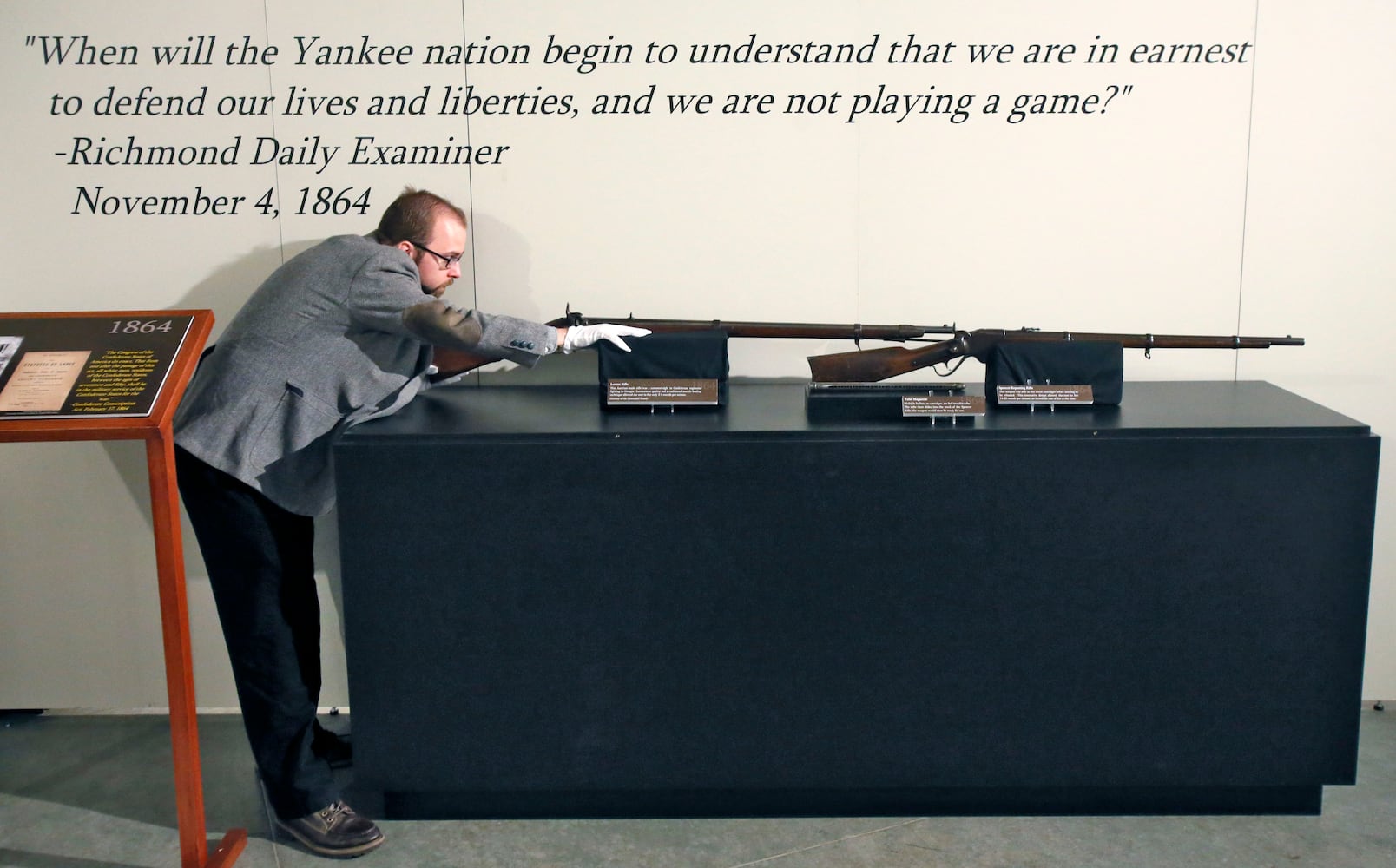

The locomotive remains on display at the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw. Richard Banz, who leads the museum, said Tuesday he was struck by the raiders’ courage. “If someone said to me, ‘Hey, listen, let’s work our way behind enemy lines and steal a train.’ I would be like, ‘Huh?’ For all of these folks, the bravery is not in question,” he said.

Gordon Jones serves as a senior military historian for the Atlanta History Center, which features the locomotive used to chase the raiders. Jones praised those who worked for years to get the medals approved for Shadrach and Wilson.

“That is a great American story,” he said. “And it just shows that individuals can still make a difference.”

Credit: Bob Andres

Credit: Bob Andres

The Marietta History Center, which is located in the former hotel where most of the raiders stayed the night before their mission, has redesigned one of the rooms to look as it did at the time.

“When we are somewhat divided in our country, to honor these men, who worked so hard to keep our country united, is really a very important part of where we are today,” said Amy Reed, who directs the center. “The timing of it all is really cool.”

Shadrach’s and Wilson’s descendants said it is particularly meaningful for Biden to present the medals just before Independence Day.

“Our country was young,” said Scott Chandler of Ohio, Wilson’s great-great-great grandson. “He had the conviction to want to keep that going the way it had been established. And he was willing to die for it. I can’t think of any sacrifice that is more meaningful in so many ways.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured