Should a Georgia railroad be allowed to force property owners in one of the state’s poorest counties to sell portions of their land for a new rail spur to serve private businesses?

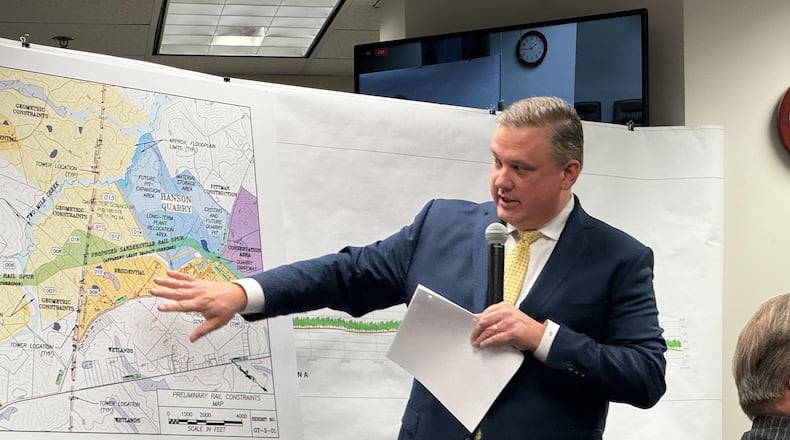

That question came before the five-member Georgia Public Service Commission (PSC), which heard more than an hour of arguments Tuesday from attorneys who debated the controversial eminent domain request. Sandersville Railroad Co. intends to condemn portions of 18 parcels to build its 4.5-mile rail spur near the town of Sparta, about 100 miles east of downtown Atlanta.

A PSC hearing officer in April signed off on Sandersville Railroad’s eminent domain request. While the officer’s decision is legally enforceable, attorneys for the property owners in the path of the proposed rail line and others with land nearby asked the commission board to review the order and consider rejecting the initial ruling.

The PSC did not take action Tuesday, and it was not immediately clear when a final ruling will be made.

The case represents one of the most significant tests of Georgia’s eminent domain laws to emerge in years and could set precedent for use of the controversial power. It pits a politically connected Georgia railroad against mostly African American property owners, some whose families have ties to their land dating to slavery.

Eminent domain is when a government or utility forces a private property owner to sell some — or all — of their land for a specific project. The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects against abuse of eminent domain and requires “just compensation” for seized property. Georgia law requires a court’s determination that a project serves a “public use,” adding that economic development alone is not enough.

Credit: Georgia Public Service Commission

Credit: Georgia Public Service Commission

Credit: Georgia Public Service Commission

Credit: Georgia Public Service Commission

Bill Maurer, a senior attorney for the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit Libertarian legal group that represents several landowners facing the eminent domain claims, told the PSC that the proposed spur doesn’t benefit the public — only a handful of private companies.

“It is a naked transfer of wealth from my clients to Sandersville and its small network of clients so those companies can get richer,” Maurer said.

Robert Highsmith, an attorney representing Sandersville Railroad, said private companies like railroads and utility providers, such as Georgia Power, have long-standing powers to condemn property to add to their rail networks and power grids. He argued his client’s plan will open up commerce, creating jobs and opportunity in Hancock County, one of Georgia’s most economically depressed areas.

“Respondents wish the law had lots of stuff in it that’s not there,” Highsmith said. " … What the law says is that one has to demonstrate that it is for a public purpose, which is defined by the (Georgia) General Assembly to include railroads and to include channels of trade.”

Named the Hanson Spur, the project would link a nearby rock quarry to an existing CSX Transportation line, and might be used by other area businesses to ship goods, including grain, wood chips and liquid asphalt. Sandersville Railroad says trains on the spur would travel less than 20 miles per hour and only run during daytime on weekdays.

In hearings last year and in filed briefs, Sandersville Railroad’s attorneys touted the potential economic boost the rail spur could bring to Hancock County, which has ranked among Georgia’s poorest for decades. The railroad says the spur will boost tax revenues, pump $1.5 million annually into the area economy and create 12 new jobs with average salaries of $90,000.

Also intervening in the case against the forced sales is the grassroots No Railroad in Our Community Coalition, which is comprised mostly of residents living near the proposed spur, but whose land is not subject to condemnation. The group is represented by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

The Republican-controlled commission primarily asked questions about the spur’s planning and logistics. Any decision by the PSC could be challenged further in Fulton County Superior Court. Maurer said he expected the PSC’s decision to be appealed regardless of the PSC’s ruling.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured