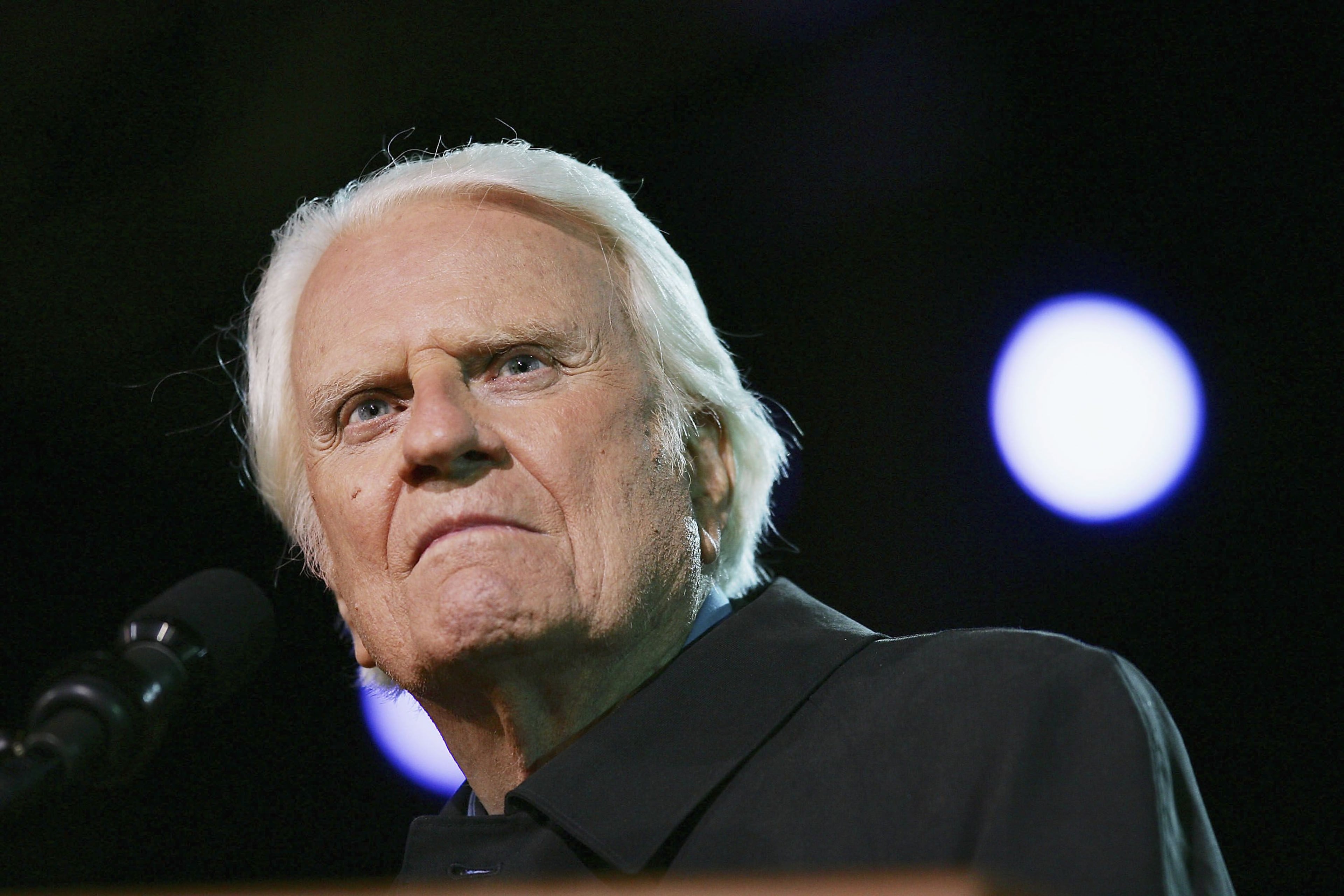

Evangelist Billy Graham is dead at 99

With the urgency of Armageddon in his flashing blue eyes, evangelist Billy Graham called the world to the altar in a career that spanned more than six decades. By tens of thousands, from across the nations of the Earth, they came.

His message, delivered in a soft, Piedmont drawl as familiar as an old hymn, never varied: Come to Jesus.

If the beliefs he preached are true, Billy Graham’s soul has gone to Jesus. Graham, 99, died early Wednesday at his home in Montreat, N.C., outside Asheville.

MORE: The AJC's coverage of Billy Graham's final Crusade

PHOTOS: Billy Graham through the years

Former President Jimmy Carter is among the many prominent voices offering messages of mourning and tribute:

“Rosalynn and I are deeply saddened to learn of the death of the Rev. Billy Graham. Tirelessly spreading a message of fellowship and hope, he shaped the spiritual lives of tens of millions of people worldwide. Broad-minded, forgiving, and humble in his treatment of others, he exemplified the life of Jesus Christ by constantly reaching out for opportunities to serve. He had an enormous influence on my own spiritual life, and I was pleased to count Reverend Graham among my advisers and friends.”

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms issued a statement as well:

“The City of Atlanta offers its sincere and heartfelt condolences to the family, friends and countless followers of Rev. Billy Graham. His inspiring leadership comforted and enlightened Christians around the world as he shared the message of the Gospel. Reverend Graham united his followers in faith and will be remembered fondly by all who claim membership in the universal congregation of peace and good will.”

Graham's official obituary included words from his final crusade, in 2005: "I have one message: that Jesus Christ came, he died on a cross, he rose again, and he asked us to repent of our sins and receive him by faith as Lord and Savior, and if we do, we have forgiveness of all of our sins."

In recent years, Graham’s poor health had kept him out of the public eye In 2010, then President Barack Obama visited Graham at his home.

“Billy Graham was a humble servant who prayed for so many - and who, with wisdom and grace, gave hope and guidance to generations of Americans,” Obama said via social media.

President Donald Trump’s tweeted remarks: “The GREAT Billy Graham is dead. There was nobody like him! He will be missed by Christians and all religions. A very special man.”

Graham was born to Frank and Morrow Graham on a farm near Charlotte on Nov. 7, 1918. The future preacher made his own trip to the altar in a traveling revival tent at age 16 to the strains of “Almost Persuaded,” according to biographer William Martin. Legend says that earlier that year members of the Charlotte Christian Men’s Club had stood in Frank Graham’s field and prayed that God would anoint someone from Charlotte to preach the gospel to the ends of the Earth.

Young Graham went on to do just that, speaking to more than 200 million people at “crusades” in stadiums, parks and arenas on six continents — and to countless millions more via television.

No other evangelist has come close to those numbers.

“There is nobody else in sight,” said Samuel Hill, professor emeritus of religion at the University of Florida. “Statistically, Graham has been doing it on a grand scale since 1947. I don’t see any rival on the planet.”

He was “one of the three most recognizable Christians in the world, along with the Pope and Mother Teresa,” Hill said. “I can’t imagine anyone else staying that long in the public eye without one smirch on his reputation.”

“Billy Frank,” as his parents called him, rose before dawn to milk cows, biographer Marshall Frady wrote. He drag-raced and parked and necked with girls. A first baseman, he wanted to be a big-league ballplayer. Once, after shaking hands with Babe Ruth at an exhibition game in Charlotte, he went three days without washing his hands.

In a 1994 interview, Graham said that he got a sense of wanderlust from his mother, Morrow Coffey Graham, who kept pictures of Japan’s Mount Fujiyama and a rose window of the Reims Cathedral in France on the wall.

“I used to sit and wonder what it was like outside where I lived,” he remembered. “Did the land look the same? Did they have hills and mountains and streams that looked like ours? I had no idea what Pennsylvania or Ohio or New York looked like.”

Before selling salvation, Graham traveled the Carolinas selling Fuller brushes. He was the company’s top salesman in the two states before going on to Bob Jones College, according to Martin.

Later he transferred to Florida Bible Institute in Temple Terrace, Fla., where he gave himself to the ministry in a late-night prayer on a golf course. He began to fill in for pastors, preach at dog tracks and saloons in central Florida, and establish himself as chaplain to the Tampa Trailer Park, Martin wrote.

In 1938, conducting his first revival, the young Presbyterian preacher was persuaded by the minister of the East Palatka (Fla.) Baptist Church to be dunked into the Southern Baptist Convention, setting the course for Graham to become the world’s best-known Baptist since John The.

The following year he got his first look at New York on a trip to the World’s Fair. “That’s when I first heard of television,” he recalled years later. “They said it was going to come to the whole country. Of course nobody believed them.”

He had little reason then to think that the newfangled device would make him one of the best-known figures on the planet.

Graham went from Florida to Wheaton College in Illinois, where he met Ruth Bell, daughter of Presbyterian missionaries to China. They were married Aug. 13, 1943, and two years later had the first of their five children.

Ruth Bell Graham died on June 14, 2007.

Throughout his life, Graham would feel the conflicting pulls of faith and family. The greatest mistake he ever made, he said, was “in taking too many speaking engagements and not spending enough time with my family.”

Nevertheless, all of his children ended up in some form of ministry. His son Franklin has been named to succeed him by the board of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

After graduating from Wheaton, Graham served a brief stint as a pastor before joining the evangelism organization Youth for Christ. A Minneapolis rally introduced him to William Bell Riley, president of that city’s Northwestern School, a complex including a seminary, Bible school and liberal arts college. The aging minister chose Graham as his successor. Though the academic career did not last, the relationship with the city did. Minneapolis remained the headquarters of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association until 2001, when Franklin Graham decided to move the main offices to Charlotte.

A 1949 crusade in Los Angeles launched Graham into prominence. Several days into services there, a gaggle of reporters and photographers showed up to cover the young evangelist. Puzzled, he asked why. According to Graham’s memoir, “Just As I Am,” a journalist replied, “You’ve just been kissed by William Randolph Hearst.” One story that circulated was that the media magnate sent his editors a directive: “Puff Graham.”

Whatever Hearst’s motivation—and Graham said he never found out — the sudden attention began a climb that never ended, even as age and ill health took their toll.

He brought his traveling revivals to Atlanta on Oct. 30, 1950. Nearly 495,000 turned out over six weeks to hear him preach God as the answer to the communist threat.

“The cross of Christ, if accepted, will spare the nation the coming judgment,” he preached. “It will change this city, will change the home, will change the church, will change the heart.”

On Sunday, Nov. 5, seated before a microphone at a table placed over second base at Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Ball Park, Graham broadcast his first-ever “Hour of Decision” radio program.

Late Chick-fil-A founder Truett Cathy attended two of the 1950 services. At the time, Cathy had only a handful of employees at his Dwarf Grill (later the Dwarf House) restaurant. He enlisted customers to go to the Graham services so they could be recognized as a group there.

“I was inspired by him.” Cathy said in a 2006 interview. “I’d always been accustomed to going to Sunday School and church. I had heard a lot about Billy Graham even at that time.”

Later, Graham established an office near the Atlanta airport for his international operations. Graham’s board would sometimes order lunch for their meetings from Cathy’s nearby restaurant.

Once, delivering the lunch, Cathy asked to meet Graham but was told he was too busy. Another time, however, he was able to chat with Graham, who gave him an autographed book.

“You could feel the presence of the Lord in his presence,” Cathy recalled.

Two years before the Atlanta crusade, Graham and the small group of men who would play a central role in his ministry for more than half a century gathered in Modesto, Calif., to devise a “manifesto” to keep them above reproach.

They chose four principles to guide them: integrity, accountability, purity and humility.

“We prayed about each one and committed our lives to those core values,” songleader Cliff Barrows recalled at a 2006 luncheon in Atlanta.

Barrows said their resolve reminded him of the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns ` in Arlington National Cemetery, where each shift says to the next that the orders remain the same. For Graham and his men, Barrows said, orders remained unchanged throughout their ministry.

As part of his commitment to purity, Graham instituted a policy of never being alone in a room with a woman other than his wife. The only exception in five decades, according to some Graham staff members, was a closed-door session with then-National Council of Churches head, Joan Brown Campbell, in her New York office.

Graham also established strict financial guidelines for himself. Those came following photographs that appeared in the Atlanta Constitution during the 1950 crusade, Graham said. A picture of a grinning Graham appeared next to a photograph of ushers handling bags of money from services in the old Ponce de Leon ballpark.

“I said, 'That’ll never happen again,’ ” Graham recalled in a 1992 interview. From that time, he said, he never accepted another “love offering,” but assembled a board of businessmen to oversee his ministry and put himself and his staff on salary.

Only once did any hint of financial scandal touch him.

The Charlotte Observer revealed in 1977 that the Graham association controlled a $22.9 million fund that helped support Wheaton College, the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, Christianity Today and others. The IRS knew about it; his supporters didn’t.

The association was concerned that if the existence of the fund was known, small donations would dry up. Graham at first justified the secrecy, quoting Matthew 6:3-4, which says to keep your charitable deeds a secret. The following year, though, the association began publishing annual financial reports, and in 1979 Graham co-founded an Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability.

Graham made his international debut with a 12-week crusade in London in 1954. British newspapers at the time sneered, according to the Associated Press, calling him a “Yankee spellbinder” and “hot-gospeller.” But some two million people attended his 72 rallies.

“Those meetings galvanized us,” Michael Baughen, former Church of England Bishop of Chester, told the AP. “It was like divine adrenaline for a jaded church.”

During the London crusade, Graham lunched with Winston Churchill. A year later, he dined with Queen Elizabeth, the first of many monarchs to make his acquaintance.

Three years later, Graham launched a record 16-week crusade in New York, during which, according to Martin, he lost 30 pounds. This stand marked the first time his crusades hit the airwaves. ABC aired four consecutive Saturday-night services beginning June 1, 1957.

Graham preached in a communist country, Yugoslavia, for the first time in 1967. A steady rain drenched a crowd of 20,000. He announced he would cut short his sermon. “No. We’ve waited too long for this,” said a voice from the crowd, and the evangelist preached on.

Some people credit Graham’s crusades behind the Iron Curtain, arranged in part by an Atlantan, Dr. Alexander Haraszti, with helping to bring about the downfall of governments there.

And long before apartheid’s death, blacks and whites prayed together at a rally Graham held in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. He struggled to bring about reconciliation in India, Northern Ireland and Korea. He had his biggest rallies in Seoul, South Korea, in 1973, preaching to 3.2 million over five days, including a stunning 1.2 million the final day.

Throughout his life, Graham consorted with the meek, the mighty and the almighty.

In his clerical globe-trotting, he spent time with Chiang Kai-shek, Indira Gandhi, Golda Meir, Mother Teresa, Jawaharlal Nehru, Prince Rainier, Yitzhak Rabin and the Shah of Iran.

He met every president back to Harry Truman and had close relationships with several.

Among the closest was his friendship with Richard Nixon. Of all the accusations surrounding the Watergate scandal that brought down the Nixon presidency, Graham was perhaps most distressed and disillusioned by the language his friend used on the White House tapes. “I felt physically sick,” Graham wrote in his memoir. “Inwardly, I felt torn apart.”

Of his friend Nixon, Graham said, “I wanted to believe the best about him for as long as I could. When the worst came out, it was nearly unbearable for me.”

Graham was pulled into the Nixon scandal in 2002 when tapes released by the National Archives revealed that in a 1972 conversation with the president, the evangelist had expressed concern that Jews had a “stranglehold” on the American media that needed to be broken.

In response to the release of the tapes, Graham issued a statement that said, in part, “I cannot imagine what caused me to make those comments, which I totally repudiate. . . Racial prejudice, anti-Semitism, or hatred of anyone with different beliefs has no place in the human mind or heart.”

Graham held two more crusades in Atlanta—in 1973 and 1994.

Developer Tom Cousins, who chaired the 1973 event, recalled in a 2006 speech that a group of civic leaders decided to invite Graham to bring the community together to try to calm the tensions of integration.

Graham hesitated to return to a city where he had held a previous revival, but finally promised to come if the city’s black clergy would extend the invitation, Cousins recalled.

At first, none would. Then Martin Luther King Sr., “Daddy” King, stepped to the forefront and spoke out on behalf of Graham.

In all of Cousins’ dealings with Graham, the evangelist showed modesty, integrity and concern for others, Cousins said: “This is a man of God.”

Before the 1994 crusade, Graham himself paid a visit to the office of the Rev. Cameron Alexander, pastor of Antioch Baptist Church North, to persuade Alexander to co-chair the revival with the late Rev. Frank Harrington.

Alexander recalled that he laid down his conditions: African-Americans should be among the leaders of every facet of the event; Graham should preach that black people and white people should love each other; the Graham team should leave a lasting legacy in the city; the congregation should sing the civil rights favorite “We Shall Overcome” on the last night.

Graham agreed to all.

As the service neared the benediction on the last night in Atlanta, Alexander remembered, “a 5,000-voice choir led more than 60,000 people. Together we sang 'We Shall Overcome.’ I will never forget that.”

Former Atlanta mayor and U.N ambassador Andrew Young, himself an ordained clergyman, said Atlanta and the world would be different without Billy Graham.

Graham, he said, preached “a gospel of love, a gospel of radical forgiveness, a gospel of salvation, a gospel of a loving God who loves us just as we are.”

Graham held the last of his large-scale crusades in 2005 at Flushing Meadows in New York.

But after New Orleans was flooded by Hurricane Katrina a few weeks later, he traveled with his son Franklin for a “Celebration of Hope,” one of the first major public events in the post-Katrina city.

Speaking from a lectern salvaged from the flood that he had used at his 1954 New Orleans Crusade, Graham told a group of Louisiana preachers that a new New Orleans could rise from the waters.

A few days later he spoke to a larger group, assuring the crowd that “God loves us with an everlasting love” and that “Christ endured physical and spiritual death so that we could be saved through faith in repentance in him.”

Graham often protested if attention seemed too focused on him.

At a 2006 luncheon in Atlanta to raise support for a Billy Graham Library in Charlotte, the evangelist chided the speakers saying, “There’s been far too much Billy Graham and not enough Jesus.”

At the same event, he recalled a time when he had several rounds of brain surgery at the Mayo Clinic.

“One night I knew I would not live,” he said. “During the dark hour, I asked the Lord to help me. All of a sudden, all my sins dating back to my childhood came in front of me.”

Then, he said, Jesus cleansed them.

Since that night, he said, “I have never had a moment of lack of peace.”

At the close of his autobiography, Graham summed up his feelings: “I don’t know the future, but I do know this: The best is yet to be! Heaven awaits us, and that will be far, far more glorious than anything we can ever imagine…”