Robert Harrell flew gliders, chased hot air balloons, fought fires, grew grapes and made wine. Mostly, he wrote stories, not about extraordinary people in faraway places, but regular folks in sometimes uncommon circumstances in locales many would hurriedly pass by.

They included Fayetteville barber Earl Brown, who’d been cutting hair since the Roosevelt era and remembered horse-drawn carriages in the parking lot; Bill Atkinson the Morgan County grave-marker hunter; and Andy Cope of Dillard, whose trout farm, unbeknownst to most, provided a scene for the movie, “Deliverance.” In it, actor Burt Reynolds is depicted spearing a fish with an arrow. Harrell’s wife, Katherine, cooked that fish, and his son, Charlie ate it.

For much of his career, Harrell had his dream job, driving Georgia’s backroads in a camper with his family and tapping out their adventures on a typewriter for regular columns published by the Atlanta Journal and Constitution when they were separate newspapers.

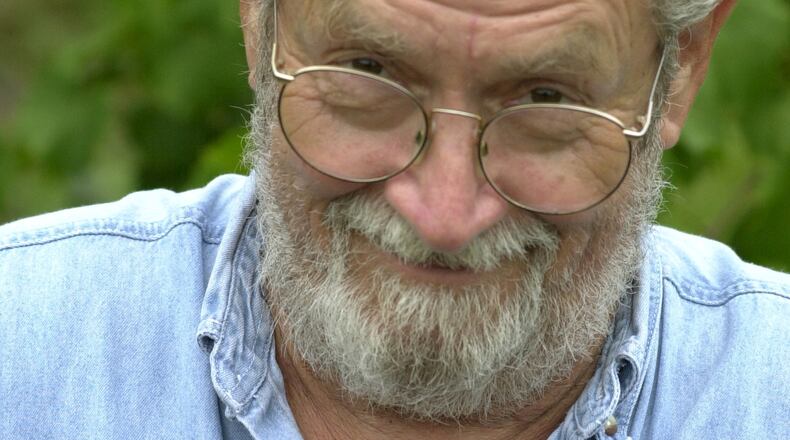

Harrell, called “Bob” by everyone who knew him, died of heart problems in Newnan July 13. He was 95. Mourners said goodbye Saturday, Aug. 27, to the late journalist. His granddaughter, the Rev. Dr. Angela Yarber, presided.

Friends and family remembered Harrell as an irascible, yet kind individual, a Southern gentleman with a healthy disregard for authority, and a generally quiet man who, when he chose to speak, could make people listen. Most of all, they recalled his stories, told often with a self-deprecating wit by a writer who didn’t like editors messing with his “poetry.”

“I was lucky he liked me,” said Cynthia Glozier, former editor of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s Clayton bureau in the early 1990s. She recalled how Harrell would refer to news editors and executives as “desk jockeys and meeting runners.”

“He always said what he thought,” Glozier said. “He was truly a truth teller and a truth seeker. He operated that way in every part of his life. He was into seeking the truth, living a true life.”

Harrell’s life began in 1927 in Morristown, Tennessee, where he grew up to become editor of the local Morristown Sun. That was after he attended the University of Tennessee and served as an Army communications officer during World War II.

Harrell married his neighbor, friend and dance partner, Katherine Minerva, in 1951, and the couple moved around Tennessee as he worked at several papers before arriving in Atlanta. The Atlanta Journal hired him as photo editor in 1958.

He shifted to feature writing, however, and he took his own photos for two long-running columns published by the Atlanta papers: Family Camping and Dateline Georgia. He drove the state in a station wagon and in a pickup with a camper cap before the newspaper supplied him with a recreational vehicle. His wife and five children traveled with him.

Harrell’s family adventures were filled with accounts of the writer poking fun at himself. In one, he described his trailer hitch and trailer coming lose and of his panic, fearing it might bypass his car or hit another’s. The disaster was averted by the safety chain. In another column, he recounted yelling at his wife and children for wandering into poison sumac — all of them immediately scrubbed off using strong soap — only to be corrected by a visiting park ranger who plucked and ate the huckleberries sprouting from those same plants.

Charlie Harrell, the youngest of the five — who include Martha, Mary, Margaret and Robert — spent the most time on the road with his mom and dad. He recalled visiting a Dillard farmer who plowed his acreage entirely with a mule, riding with the harbormaster to visit a ship anchored near Savannah, and, as a little boy, witnessing the fish kill for the “Deliverance” scene. In an old photo of Charlie standing beside the fish, the trout looks as long as the boy is tall.

The newspaper ended his column in the late ‘70s and Harrell returned to the office as a regular reporter. By this time, he had moved from Atlanta to a 40-acre farm in Newnan, where he and his wife built a log cabin and grew muscadine grapes. He would become a grandfather of four, and a great-grandfather of four. Katherine Harrell died in 2008.

But Harrell’s adventures never stopped.

He worked as a volunteer firefighter with Robert and then called in fire reports to the newspaper. The younger Harrell, who became a professional firefighter, once pulled his father out of a burning home when the floor gave way. Harrell also took up flying gliders and assisting hot air balloonists by following them to their destinations.

“He was always making a plan, even up until the end of his life,” Mary Harrell said.

Harrell retired from the newspaper in 1992. On his way out the door, fellow reporter Rick Minter asked if he’d ever come back to visit.

“Don’t count on it,” was Harrell’s reply, Minter recalled.

Harrell had other things to do.

About the Author